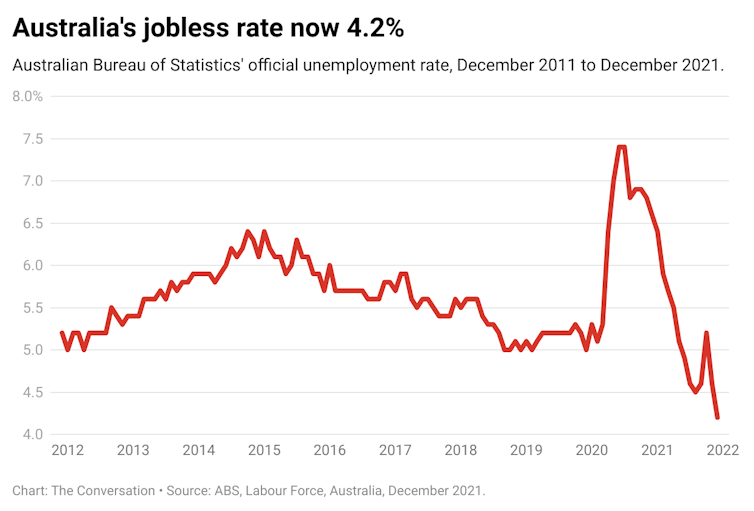

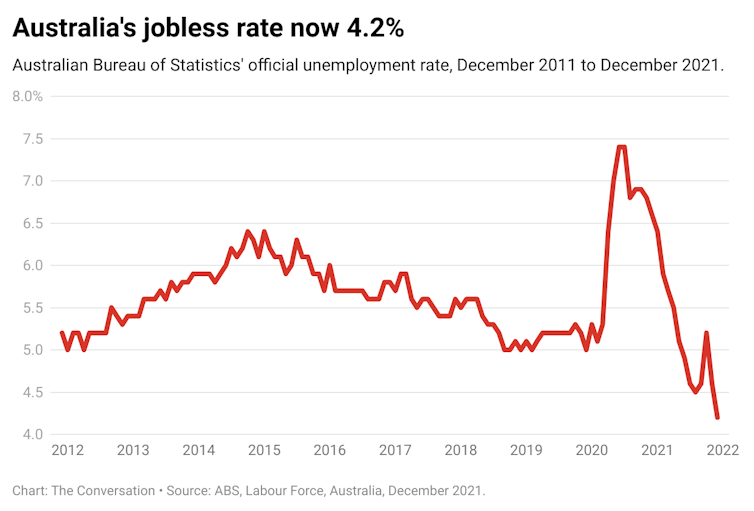

It would be nice to think Australia’s low unemployment rate – now 4.2%, the lowest since August 2008 – is here to stay.

We’ve been waiting a long time to see this. In the decade before the onset of COVID-19 the jobless rate hardly moved. In March 2010 it was 5.4%. Ten years later, in March 2020, it was 5.3%. In between the lowest the rate was to 4.9% - and then just for two months.

CC BY

In 2021 the unemployment rate was under 5% in six out of 12 months.

A lower rate of unemployment makes us all better off. It means more of the nation’s productive resources are being put to work, and higher living standards for those extra people employed and their families.

Even with the effects of Omicron, there are good reasons to think the rate will fall further in 2022.

The bigger question is whether whatever lower rate we achieve can be sustained once all the effects of the pandemic are behind us. This will depend largely on how macroeconomic policy makers handle the transition.

High job vacancies

One reason to expect the rate to go lower in 2022 is recent employment growth – 365,000 in November, and 65,000 in December. With that pace of growth it’s likely there’s more to come, especially given the high level of job vacancies.

Had the vacancy rate at the end of 2021 been the same as before COVID-19, an extra 158,000 jobs would have been filled. Just half of those jobs going to the unemployed would have seen the December unemployment rate drop to 3.6%.

Read more:

Australia has record job vacancies, but don't expect higher wages

Uncertainties make it difficult to predict exactly how much lower the jobless rate could go, or for how long. That will depend on macroeconomic policy – the reason the unemployment rate is where it is now.

Government action has been crucial

The big reason the unemployment rate has fallen is due to growth in the proportion of the population who are employed accelerating since mid-2021.

When you think about what changed in 2021 to make this happen, government policy has to be the main explanation.

Government spending on COVID-related programs has added considerably to gross domestic product, increasing employment.

Closed borders may also have added to GDP – by as much as 1.25% per annum, according to economist Saul Eslake – due to Australians redirecting spending from international travel to domestic consumption.

What follows is that a low rate of unemployment will depend on the policy makers being willing to continue to provide stimulus to economic activity.

An opposing force

One headwind blowing the unemployment rate higher may be faster growth in the labour-force participation rate, which measures the proportion of the population who want to work.

Before COVID-19 the participation rate had been increasing rapidly. With COVID-19 it slowed, due to reasons such as parents having to withdraw from the labour force to care for children.

CC BY

Should growth in the labour-force participation rate return to its previous pace once the impact of COVID-19 recedes, the rate of unemployment will be pushed back up.

Read more:

Just 4.5% during lockdowns? The unemployment rate is now meaningless

Statistics for young workers

Issues to do with measurement may also be temporarily making the rate of unemployment artificially low.

The strongest employment growth from March 2020 to December 2021 was for those aged 15 to 24 years.

Younger workers were hardest hit during the 2020 downturns associated with COVID-19. But by December 2021 the proportion of young people employed was 3.5 percentage points higher than in March 2020. This compares with the employment rate being 1.2 percentage points higher than before the pandemic for those aged 25-64 years, and 0.9 percentage points higher for those 65 years and older.

CC BY

Should growth in the labour-force participation rate return to its previous pace once the impact of COVID-19 recedes, the rate of unemployment will be pushed back up.

Read more:

Just 4.5% during lockdowns? The unemployment rate is now meaningless

Statistics for young workers

Issues to do with measurement may also be temporarily making the rate of unemployment artificially low.

The strongest employment growth from March 2020 to December 2021 was for those aged 15 to 24 years.

Younger workers were hardest hit during the 2020 downturns associated with COVID-19. But by December 2021 the proportion of young people employed was 3.5 percentage points higher than in March 2020. This compares with the employment rate being 1.2 percentage points higher than before the pandemic for those aged 25-64 years, and 0.9 percentage points higher for those 65 years and older.

CC BY

The strength of employment growth for the young – given all we know about the increasing difficulties they faced in the labour market in the 2010s – is surprising.

My guess is it may in part be due to young Australian permanent residents taking over jobs previously held by international students and working holiday makers, and being more likely to be captured in official surveys.

Read more:

The economy can't guarantee a job. It can guarantee a liveable income for other work

In that case,total employment of the young may not actually have changed by much, but the statistics show it increasing because of who is doing the work.

Before COVID-19 we could reasonably have expected the rate of unemployment today to be 5%. Instead, we’re at 4.2% and looking ahead in 2022 to further falls in unemployment. What lies beyond that is less certain.

References^ (creativecommons.org)^ (theconversation.com)^ (drive.google.com)^ (creativecommons.org)^ (theconversation.com)^ (creativecommons.org)^ (theconversation.com)Authors: Jeff Borland, Professor of Economics, The University of Melbourne

CC BY

The strength of employment growth for the young – given all we know about the increasing difficulties they faced in the labour market in the 2010s – is surprising.

My guess is it may in part be due to young Australian permanent residents taking over jobs previously held by international students and working holiday makers, and being more likely to be captured in official surveys.

Read more:

The economy can't guarantee a job. It can guarantee a liveable income for other work

In that case,total employment of the young may not actually have changed by much, but the statistics show it increasing because of who is doing the work.

Before COVID-19 we could reasonably have expected the rate of unemployment today to be 5%. Instead, we’re at 4.2% and looking ahead in 2022 to further falls in unemployment. What lies beyond that is less certain.

References^ (creativecommons.org)^ (theconversation.com)^ (drive.google.com)^ (creativecommons.org)^ (theconversation.com)^ (creativecommons.org)^ (theconversation.com)Authors: Jeff Borland, Professor of Economics, The University of MelbourneRead more