Now we know. The Reserve Bank has spelled out what it will do when rates approach zero

- Written by Stephen Kirchner, Program Director, Trade and Investment, United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney

Last night, in a much anticipated speech broadcast live on the Reserve Bank’s website[1], Governor Phil Lowe laid out in very clear terms the circumstances in which the bank would resort to quantitative easing and the way in which it would implement it.

Quantitative easing is simply a change in the way it eases monetary policy when the official interest rate approaches zero.

Usually it does it by cutting the so-called cash rate[2], which is the rate banks pay each other for money deposited overnight.

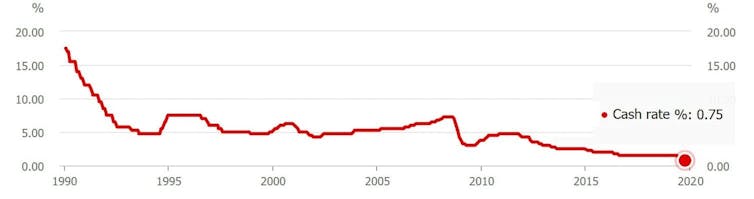

Eight years ago the cash rate was 4.5%. Three years ago it was 1.5%. After the most recent three cuts in June, July and October, it is just 0.75%

Source: RBA[3]

Last night, Governor Lowe said the effective lower bound was 0.25%[4]. Rather than let the cash rate get any lower or negative (an option he explicitly ruled out), the bank will push down other longer-term rates by buying government bonds.

It’s the “quantitative easing” approach adopted by the US Federal Reserve between 2009 and 2014.

Read more:

Below zero is ‘reverse’. How the Reserve Bank would make quantitative easing work[5]

Government bonds are sold by governments in return for money, a means of borrowing. The buyer gets guaranteed interest payments and a guarantee that their money will be returned in full after three, five, ten or even 20 years depending on the length of the bond.

Once issued, bonds can be traded on a market, and the price at which they change hands can be expressed as an implied interest rate, which becomes the risk-free rate against which all other interest rates are benchmarked.

How quantitative easing would work

Buying bonds from investors would push down that risk-free rate, pushing down the entire structure of long-term interest rates.

All other things being equal, this should also push down the exchange rate by reducing the return on Australian dollar denominated financial investments.

Governor Lowe indicated he might buy state government bonds as well as Commonwealth bonds.

Importantly, he argued that although the bank would be mindful of the need to ensure private banks had enough access to the bonds they needed to hold for regulatory purposes, those holdings would not be an impediment to quantitative easing.

He ruled out buying residential mortgage-backed securities and other private assets given that those markets are currently functioning well and Reserve Bank purchases could distort them.

Read more:

RBA update: Governor Lowe points to even lower rates[6]

The approach borrows heavily from the US Fed.

As in the US, Lowe says quantitative easing would be complemented by “forward guidance,” where the Reserve Bank would signal early how long-term interest rates would be kept low and the circumstances in which it expected to raise them again.

The guidance is designed to influence market expectations for future interest rates, enhancing the effectiveness of cuts in long term interest rates.

When it would happen

Source: RBA[3]

Last night, Governor Lowe said the effective lower bound was 0.25%[4]. Rather than let the cash rate get any lower or negative (an option he explicitly ruled out), the bank will push down other longer-term rates by buying government bonds.

It’s the “quantitative easing” approach adopted by the US Federal Reserve between 2009 and 2014.

Read more:

Below zero is ‘reverse’. How the Reserve Bank would make quantitative easing work[5]

Government bonds are sold by governments in return for money, a means of borrowing. The buyer gets guaranteed interest payments and a guarantee that their money will be returned in full after three, five, ten or even 20 years depending on the length of the bond.

Once issued, bonds can be traded on a market, and the price at which they change hands can be expressed as an implied interest rate, which becomes the risk-free rate against which all other interest rates are benchmarked.

How quantitative easing would work

Buying bonds from investors would push down that risk-free rate, pushing down the entire structure of long-term interest rates.

All other things being equal, this should also push down the exchange rate by reducing the return on Australian dollar denominated financial investments.

Governor Lowe indicated he might buy state government bonds as well as Commonwealth bonds.

Importantly, he argued that although the bank would be mindful of the need to ensure private banks had enough access to the bonds they needed to hold for regulatory purposes, those holdings would not be an impediment to quantitative easing.

He ruled out buying residential mortgage-backed securities and other private assets given that those markets are currently functioning well and Reserve Bank purchases could distort them.

Read more:

RBA update: Governor Lowe points to even lower rates[6]

The approach borrows heavily from the US Fed.

As in the US, Lowe says quantitative easing would be complemented by “forward guidance,” where the Reserve Bank would signal early how long-term interest rates would be kept low and the circumstances in which it expected to raise them again.

The guidance is designed to influence market expectations for future interest rates, enhancing the effectiveness of cuts in long term interest rates.

When it would happen

RBA governor Philip Lowe addressed business economists in Sydney on Tuesday night.

DEAN LEWINS/AAP

In addition to “how,” Governor Lowe spelled out “when” – the economic circumstances in which the bank would resort to quantitative easing.

It would do it when the cash rate was at 0.25% and inflation and unemployment were moving away from its objectives.

The bank targets 2-3% inflation on average over time and has recently identified 4.5% as the “full employment” unemployment rate.

Importantly, Lowe emphasised that the Australian economy has not yet reached the point where a cash rate as low as 0.25% would be needed and argued quantitative easing was unlikely to be needed in future.

The cash rate is at present 0.75%. Setting 0.25% as the effective lower bound gives the Governor 0.5 percentage points left to cut before implementing quantitative easing.

Implicitly, Governor Lowe is saying that those cuts of 0.5 percentage points will be enough to stabilise the economy.

A pause for a breath at 0.25%

Lowe also indicated the bank would not seamlessly transition to quantitative easing.

He implied there was an additional hurdle or threshold that would need to be crossed, suggesting he would be reluctant to make the transition.

His big problem is that neither inflation nor the unemployment rate are moving in the right direction.

The bank has undershot its inflation target since the end of 2014, giving the economy a weak starting point going into an emerging global downturn.

My research[7] on the US experience for the United States Studies Centre shows that the main problem with is quantitative easing was that it was not done soon enough or aggressively enough.

It might be better to be bold

While quantitative easing was effective, it could have been made more so had what was going to happen been made clearer.

The Fed went out of its way to limit the transmission of quantitative easing to the rest of the economy, fearful it would be too potent and lead to excessive inflation.

Those concerns proved misplaced. By pulling its punches, the Fed ended up being less effective and having to pursue quantitative easing for longer than if it had used it more aggressively.

Governor Lowe’s very obvious reluctance to go down the quantitative easing route suggests the Reserve Bank is in danger of making the same mistake, but it is not too late to learn from what happened in the US.

RBA governor Philip Lowe addressed business economists in Sydney on Tuesday night.

DEAN LEWINS/AAP

In addition to “how,” Governor Lowe spelled out “when” – the economic circumstances in which the bank would resort to quantitative easing.

It would do it when the cash rate was at 0.25% and inflation and unemployment were moving away from its objectives.

The bank targets 2-3% inflation on average over time and has recently identified 4.5% as the “full employment” unemployment rate.

Importantly, Lowe emphasised that the Australian economy has not yet reached the point where a cash rate as low as 0.25% would be needed and argued quantitative easing was unlikely to be needed in future.

The cash rate is at present 0.75%. Setting 0.25% as the effective lower bound gives the Governor 0.5 percentage points left to cut before implementing quantitative easing.

Implicitly, Governor Lowe is saying that those cuts of 0.5 percentage points will be enough to stabilise the economy.

A pause for a breath at 0.25%

Lowe also indicated the bank would not seamlessly transition to quantitative easing.

He implied there was an additional hurdle or threshold that would need to be crossed, suggesting he would be reluctant to make the transition.

His big problem is that neither inflation nor the unemployment rate are moving in the right direction.

The bank has undershot its inflation target since the end of 2014, giving the economy a weak starting point going into an emerging global downturn.

My research[7] on the US experience for the United States Studies Centre shows that the main problem with is quantitative easing was that it was not done soon enough or aggressively enough.

It might be better to be bold

While quantitative easing was effective, it could have been made more so had what was going to happen been made clearer.

The Fed went out of its way to limit the transmission of quantitative easing to the rest of the economy, fearful it would be too potent and lead to excessive inflation.

Those concerns proved misplaced. By pulling its punches, the Fed ended up being less effective and having to pursue quantitative easing for longer than if it had used it more aggressively.

Governor Lowe’s very obvious reluctance to go down the quantitative easing route suggests the Reserve Bank is in danger of making the same mistake, but it is not too late to learn from what happened in the US.

References

- ^ broadcast live on the Reserve Bank’s website (webcasting.boardroom.media)

- ^ cash rate (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ Source: RBA (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ effective lower bound was 0.25% (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ Below zero is ‘reverse’. How the Reserve Bank would make quantitative easing work (theconversation.com)

- ^ RBA update: Governor Lowe points to even lower rates (theconversation.com)

- ^ research (www.ussc.edu.au)

Authors: Stephen Kirchner, Program Director, Trade and Investment, United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney