Review finds most retirees well off, some very badly off

- Written by Helen Hodgson, Professor, Curtin Law School and Curtin Business School, Curtin University

The government’s Retirement Incomes Review[1] paints an encouraging picture of the finances of retired Australians.

Most are at least as well off in retirement as they were while working, and most are more financially satisfied and less financially-stressed than Australians of working age.

But not all. The huge exception[2] is retirees who do not own their own homes.

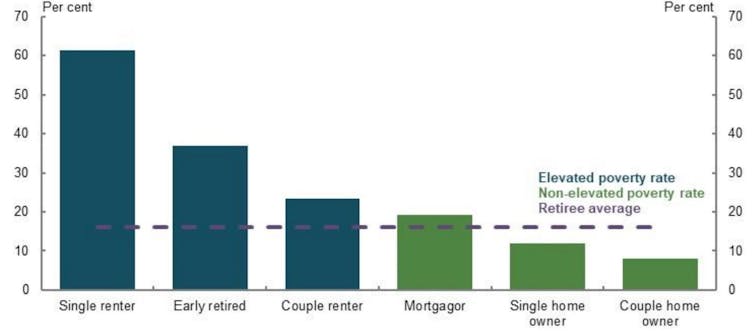

Whereas very few retired home owners are in poverty, most retired renters are.

Income poverty rates of retirees

Note: Data relates to 2017-18 financial year. Elevated poverty rate defined as 5 percentage points above retiree average.Retirees are where household reference person is aged 65 and over. There is overlap between some categories, for example, early retired and renter categories. Early retired means aged 55-64 and not in the labour force. Housing costs includes the value of both principal and interest components of mortgage repayments. Source: Analysis of ABS Survey of Income and Housing Confidentialised Unit Record File, 2017-18[3]

Note: Data relates to 2017-18 financial year. Elevated poverty rate defined as 5 percentage points above retiree average.Retirees are where household reference person is aged 65 and over. There is overlap between some categories, for example, early retired and renter categories. Early retired means aged 55-64 and not in the labour force. Housing costs includes the value of both principal and interest components of mortgage repayments. Source: Analysis of ABS Survey of Income and Housing Confidentialised Unit Record File, 2017-18[3]

So bad is the divide, the review found that even a 40% increase in Commonwealth Rent Assistance (the payment for pensioners) would reduce financial stress among renters by only 1%.

This is because rent assistance is low, covering only about 13% of the cost of renting.

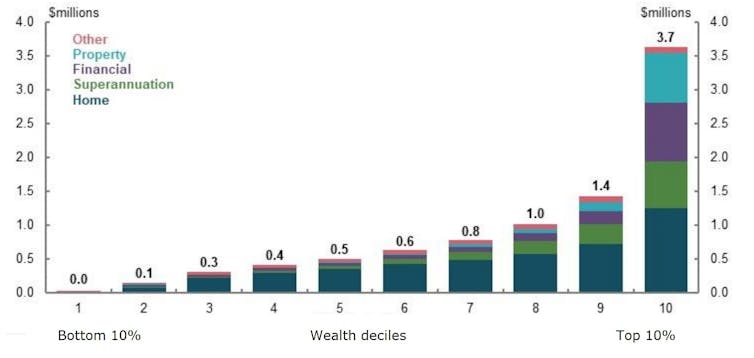

Retirees who own their own homes don’t have to pay rent (and can still get the pension should their wealth be tied up in their home), and have a source of wealth that usually eclipses both their own superannuation and the wealth of renters.

Equivalised household wealth by asset type, for retirees

Note: Retirees are defined as households where the reference person is aged 65 or older and is no longer in the labour force. Household wealth has been equivalised using the OECD equivalence scale in order to take account of differences in a household’s size and composition. Values in 2017-18 dollars. ABS, Retirement Incomes Review

Note: Retirees are defined as households where the reference person is aged 65 or older and is no longer in the labour force. Household wealth has been equivalised using the OECD equivalence scale in order to take account of differences in a household’s size and composition. Values in 2017-18 dollars. ABS, Retirement Incomes Review

Most people do not regard their home as a retirement asset, a view compounded by rules that exempt it from taxes and the pension assets test.

They are also reluctant to borrow against the value of their home using facilities such as the Pension Loans Scheme[4], for the same reasons they are reluctant to touch any of the wealth they retire with.

Data provided to the review by a large super fund shows its members typically die with 90% of what they had at retirement.

Most retirees don’t use what they’ve got

Another study finds age pensioners die with about 90% of what they had on retirement.

Partly the reasons are psychological. The review says words such as “investments”, “savings” and “nest eggs” imply the assets aren’t for living on.

Before compulsory super, employer-sponsored schemes usually paid “defined” benefits that could be measured in terms of income per year.

In the new system, designed to break the connection between workers and specific employers, benefits were “accumulated” in funds that could most easily be measured by the amount in them.

Read more: Why we should worry less about retirement - and leave super at 9.5%[5]

It is difficult for most people to see how a lump sum converts into income stream, and even more difficult when it depends on the interaction with the pension.

Another reason retirees hang on to what they had on retirement might be a genuine (if misplaced) concern about the unexpected.

In fact, health and aged care costs are heavily subsidised. Most people’s spending on them doesn’t increase significantly throughout retirement, yet many people seem unaware of how little of their own funds they will need.

Partly this is because of the complexity of the aged care and health care systems and how poorly they are explained.

It’s created two systems

Providing help to retirees who actually need it (mainly renters, many of them single women) and getting people with assets in the form of superannuation, savings and housing to actually use them rather than pass them on in bequests are the two key challenges identified in the report.

They are problems that boosting the rate of compulsory super contributions (as pushed for by the funds and presently leglislated[6]) won’t help with.

They are set to become worse.

Although home ownership rates remain high for people over the age of 65, a growing number of Australians are not entering the housing market.

Over 15 years, the number of Australians over 65 who do not own their home outright is expected to double[7].

Read more: Fall in ageing Australians' home-ownership rates looms as seismic shock for housing policy[8]

As the amount in super funds grows (boosted by the legislated increase in compulsory contributions, should it take place), Australians with super are going to have even more relative to what they need and even less need to make use of it.

The report makes no recommendations, and doesn’t suggest that the solutions are easy.

Widening the pension asset test to include the home would leave many homeowners worse off and could generate distrust and destabilise the system.

Read more: Retirement incomes review finds problems more super won't solve[9]

Getting more Australians into home ownership has proved difficult and could never be a solution for all Australians, in any case.

We already have in place rules that require retirees to draw down their super, but often they withdraw the minimum amount permitted and then reinvest much of it in another savings vehicle outside of super.

We’ve created a system where most have enough or more than enough to retire on and others get nothing like enough.

References

- ^ Retirement Incomes Review (treasury.gov.au)

- ^ huge exception (treasury.gov.au)

- ^ Source: Analysis of ABS Survey of Income and Housing Confidentialised Unit Record File, 2017-18 (treasury.gov.au)

- ^ Pension Loans Scheme (www.servicesaustralia.gov.au)

- ^ Why we should worry less about retirement - and leave super at 9.5% (theconversation.com)

- ^ presently leglislated (theconversation.com)

- ^ expected to double (theconversation.com)

- ^ Fall in ageing Australians' home-ownership rates looms as seismic shock for housing policy (theconversation.com)

- ^ Retirement incomes review finds problems more super won't solve (theconversation.com)

Authors: Helen Hodgson, Professor, Curtin Law School and Curtin Business School, Curtin University