how do police undertake major crime investigations?

- Written by Terry Goldsworthy, Associate Professor in Criminology, Bond University

Recent high-profile criminal cases, such as the suspected death of William Tyrrell[1] and the abduction of Chloe Smith[2], have captured the attention of the media and the public.

As a former detective inspector, I investigated and managed more than 25 homicide investigations and many other major crimes during 28 years with the Queensland Police Service.

So what happens behind the scenes in a major crime investigation. And how does the investigation of major crime differ from volume crime?

The difference between major crime and volume crime

Homicides are the most obvious type of major crime, but it can also include robbery, rape and other serious offences such as organised crime.

The Queensland Crime and Corruption Commission’s list of major crime offences[3] includes drug trafficking, fraud, money laundering, criminal paedophilia and homicide.

The Australian Institute of Criminology defines volume crime[4] as offences that account for the largest proportion of crime recorded by the police. These include unlawful entry, assaults, motor vehicle theft and theft.

There is a difference between the way major crime and volume crime are investigated. Major crime investigations can take years for some cases, such as the murder of 13-year-old Daniel Morcombe[5], which took 11 years to reach a conviction.

In major crime, there is a clear division of labour rather then just one officer doing everything, as is usually the case in volume crime investigations. Assigned roles include the investigation manager, the arrest team, other investigators, an intelligence cell and specialist support staff.

Major crimes such as homicides involve dedicated taskforces or operations containing large teams of detectives, conducting parallel lines of inquiry.

Usually, a major incident room is set up.

Read more: Cleo Smith case: how 'cognitive interviewing' can help police compile the most reliable evidence[6]

Clear up rates for major crime

This ability to put greater investigative effort and specialist support into major crime investigations contributes to much higher “clear-up rates” – when a suspect is identified and proceedings are begun – for these types of offences.

A New South Wales[7] study showed that, from 2007 to 2016, 65% of murders were cleared by police within 90 days. The same study noted clear-up rates for property offences were much lower than for violent offences, including murder. In Queensland, 96% of murders reported[8] in 2019–20 were cleared.

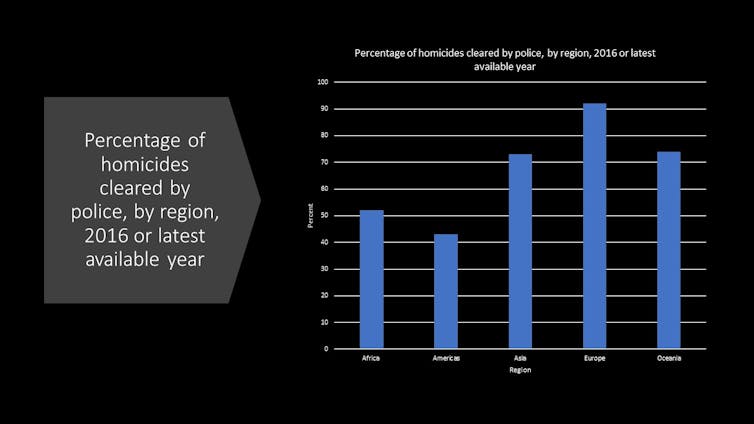

Australia’s clearance rates for homicide compare well to the rest of the world. The United Nations Global study on homicide[9] indicates clearance rates range between 50% and 90%.

The hunt for information

Most major investigations are a process of moving from having little information about the crime to having a lot. It is essentially an exercise in information management. Investigators need to acquire information to build a plausible account of what has happened.

Investigators do this by identifying, interpreting and assembling information into a form that shows whether a crime has been committed, and who is responsible for that crime. Sources of information can include crime scene material, intelligence databases, witnesses, victims and the media.

An investigative model

There is no standardised investigative process or model. The United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime provides some guidance on how to progress through a generic reactive investigation in its crime investigation toolkit[10].

In the United Kingdom, the College of Policing[11] provides guidance on the investigative process. However, it notes that every investigation is different, and so may require a different path to solving the case.

In 2001, as part of a research project in conjunction with the Queensland Police Service, I developed an investigative model[12]. It outlined several stages:

- crime scene

- initial assessment

- investigation

- target

- arrest.

In the course of an investigation, police can return to any stage and begin a new line of inquiry. We have seen this occur with the disappearance of William Tyrrell, with police returning to the original crime scene[13] some seven years later after receiving new information.

Read more: How do police forensic scientists investigate a case? A clandestine gravesite recovery expert explains[14]

No matter what model is used, there are decisions that the management team of the investigation will need to make as it moves through the stages:

knowledge decisions are concerned with how particular information should be interpreted and treated by the investigative team

tactical decisions relate to what should be done, when and by whom

logistical decisions concern the operational supports and resources to be dedicated to an investigation

legal decisions need to be made to ensure any actions taken by the investigative team are legal and admissible in a court case.

The role of media and technology

The media are a great investigative tool and can be used to apply tactical pressure to suspects and drive the search for information from the public. The extensive coverage of high-profile cases, such as that of William Tyrrell[15], is an example of this. The use of the media can also coincide with covert policing strategies, such as listening devices, designed to target potential suspects.

Technology is now also playing a much larger role in major investigations. We all leave digital footprints, be they passive (your mobile phone searching for a signal from a cell tower) or active (using your phone to pay for fuel at a geographic location).

In one triple-murder investigation[16] that I managed, the offenders were tracked up and down the eastern seaboard of Australia, and to the murder scenes, using their mobile phone data.

One thing that hasn’t changed over time is the importance of the investigative effort in the early stages of any major crime, but particularly murders. I have seen first-hand[17] how putting the effort in early in terms of long hours and adequate resources can result in solving major crime.

References

- ^ William Tyrrell (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ abduction of Chloe Smith (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ list of major crime offences (www.ccc.qld.gov.au)

- ^ volume crime (www.aic.gov.au)

- ^ the murder of 13-year-old Daniel Morcombe (theconversation.com)

- ^ Cleo Smith case: how 'cognitive interviewing' can help police compile the most reliable evidence (theconversation.com)

- ^ New South Wales (www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au)

- ^ Queensland, 96% of murders reported (www.qgso.qld.gov.au)

- ^ United Nations Global study on homicide (www.unodc.org)

- ^ crime investigation toolkit (www.un.org)

- ^ College of Policing (www.app.college.police.uk)

- ^ I developed an investigative model (research.bond.edu.au)

- ^ police returning to the original crime scene (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ How do police forensic scientists investigate a case? A clandestine gravesite recovery expert explains (theconversation.com)

- ^ such as that of William Tyrrell (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ one triple-murder investigation (www.goldcoastbulletin.com.au)

- ^ I have seen first-hand (research.bond.edu.au)

Read more https://theconversation.com/explainer-how-do-police-undertake-major-crime-investigations-172610