Most Australians support First Nations Voice to parliament: survey

- Written by Jacob Deem, Lecturer - Law, CQUniversity Australia

The deaths in custody of five Indigenous Australians[1] since March highlight the treatment of First Nations peoples as one of the most pressing policy issues facing the Australian government.

They also come at a time when recognition of First Nations peoples in the Constitution faces many barriers, including diminishing support from within the government[2].

Despite this, our research reveals substantial public support for a First Nations Voice to parliament, pressing the case for action.

A First Nations Voice to parliament has been the focus of the push for constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians since 2015. After being endorsed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders in the Uluru Statement from the Heart[3] in 2017, the proposed Voice has also become the centre of efforts to give Indigenous Australians a permanent say in decisions affecting them, and progress meaningful reconciliation.

There are two different ideas for a Voice. The first is to enshrine it in the Constitution, as outlined in the Uluru Statement; the second is simply to legislate it.

Our research shows greater support for the former, which would require a national referendum. It would also require a change in the government’s current preference for a legislated Voice.

Politically, there is a long history of resistance[4] to First Nations people having a voice in parliament. Recently, there has also been debate over whether enough Australians would support this reform.

Read more: Indigenous recognition is more than a Voice to Government - it's a matter of political equality[5]

Substantial support for a First Nations Voice

In 2017, Griffith University’s Australian Constitutional Values Survey showed solid public support[6] from the start, contrary to the fears of many leaders.

Now, the 2021 Australian Constitutional Values Survey by CQUniversity and Griffith University shows over 60% of Australians remain in favour of a First Nations Voice to parliament in some form.

The nationally representative online survey of over 1,500 Australians was conducted in February. While a quarter of Australians remain undecided, most of those had not heard of the proposal. Only one in eight respondents (12%) was opposed to the idea of a First Nations Voice.

The feedback on why Australians do or don’t value the reform comes at a crucial time, as submissions are being gathered by the federal government’s co-design process[7] on what the Voice should look like.

Asked why they were in favour, most respondents said establishing a First Nations Voice would be the “right thing to do”, including as a step towards reconciliation. Many respondents also acknowledged the Voice’s role in addressing the ongoing effects of European colonisation.

Respondents also viewed the Voice as an important way of listening to First Nations peoples, improving policies and making a practical difference. Others saw the Voice as a way to recognise the special status of First Nations peoples as the country’s traditional owners.

These objectives and principles also have an impact on the form most Australians think the Voice should take.

Read more: Proposed Indigenous 'voice' will be to government rather than to parliament[8]

Preference for constitutional rather than legislated Voice

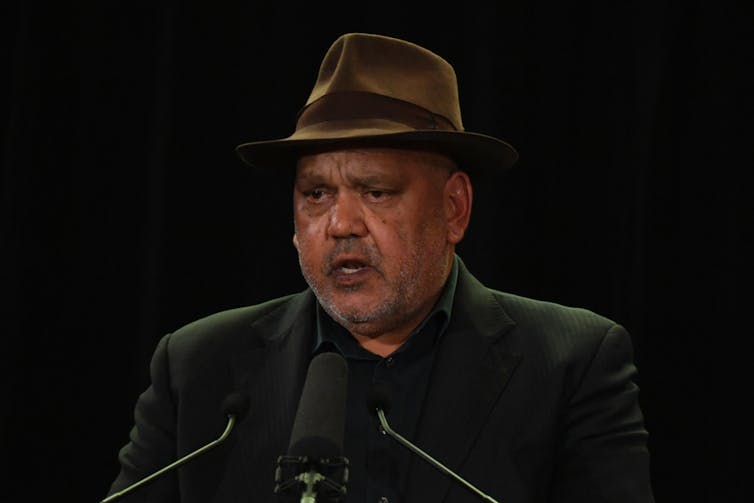

Voice proposals began as the pathway to meaningful recognition of Indigenous peoples in Australia’s Constitution, described by Indigenous leader Noel Pearson[9] as our “longest standing and unresolved project for justice”.

However, some leaders still question the constitutional goal, fearing a lack of public support[10].

Constitutional recognition would require a strong vote in a national referendum, similar to the historic result in 1967[11] that allowed[12] government to make laws for Aboriginal people and include them in the census.

Indigenous leader Noel Pearson describes constitutional recognition as our ‘longest standing and unresolved project for justice’.

AAP/Mick Tsikas

Indigenous leader Noel Pearson describes constitutional recognition as our ‘longest standing and unresolved project for justice’.

AAP/Mick Tsikas

A predictable “fallback” is to simply legislate the Voice rather than enshrine it in the Constitution. This strategy was reinforced by Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s[13] insistence that constitutional change is not on the agenda, claiming a lack of any

clear consensus proposal at this stage, which would suggest mainstream support in the Indigenous community or elsewhere.

But our survey indicates this fallback option would fall short of public expectations. Over half of all respondents (51.3%) said they would be in favour of enshrining the Voice via constitutional change. Only a quarter (26.3%) said they would still be in favour of the Voice as only a legislated reform, with no constitutional recognition.

Read more: Lessons of 1967 referendum still apply to debates on constitutional recognition[14]

Many Australians are still undecided, but the results show that if the plan is said to be supported by Indigenous Australians, this would make a difference for many of those on the fence.

The scope for a positive 1967-style result, therefore, remains substantial and real.

Compared to a legislated Voice, a constitutional Voice would benefit from greater stability because its existence would be guaranteed. A constitutional Voice would also deliver recognition[15] called for by many Indigenous Australians.

The low public support for a legislated option also reinforces arguments that successful constitutional change would give more popular legitimacy than a legislated Voice[16], directly engaging the entire community and making the reform part of Australian history.

The results also indicate Australians see the practical value of making the Voice permanent by putting it in Australia’s founding document. This means it could not be simply abolished by future parliaments.

With only 21% of Australians against a constitutional Voice - as opposed to 34% against a purely legislated one - there is wide opportunity to pave the way to successful constitutional recognition once the co-design process has resolved questions of the Voice’s functions and form.

Creating a First Nations Voice to parliament is now the obvious way forward. The government is committed to establishing it, and general public support is solidifying. This is a remarkable testament to how the idea has resonated with people.

But the important lesson to consider is that the core of public support lies in establishing the Voice in the Constitution as a step on the journey towards reconciliation.

References

- ^ deaths in custody of five Indigenous Australians (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ diminishing support from within the government (nit.com.au)

- ^ Uluru Statement from the Heart (ulurustatement.org)

- ^ long history of resistance (theconversation.com)

- ^ Indigenous recognition is more than a Voice to Government - it's a matter of political equality (theconversation.com)

- ^ solid public support (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ co-design process (www.niaa.gov.au)

- ^ Proposed Indigenous 'voice' will be to government rather than to parliament (theconversation.com)

- ^ Indigenous leader Noel Pearson (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ fearing a lack of public support (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ historic result in 1967 (theconversation.com)

- ^ allowed (www.aph.gov.au)

- ^ Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ Lessons of 1967 referendum still apply to debates on constitutional recognition (theconversation.com)

- ^ recognition (theconversation.com)

- ^ more popular legitimacy than a legislated Voice (theconversation.com)

Read more https://theconversation.com/most-australians-support-first-nations-voice-to-parliament-survey-157964