From Elvis to Dolly, celebrity endorsements might be the key to countering vaccine hesitancy

- Written by Michelle O'Shea, Senior Lecturer, School of Business, Western Sydney University

The Australian government has secured close to 54 million doses[1] of the AstraZeneca vaccine, as well as 20 million doses[2] of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

This is more than enough coronavirus vaccines for the entire population — and then some. But with vaccine hesitancy on the rise[3] in Australia, questions remain over what methods the government will use to persuade enough people to get the jab.

According to a recent study, only three out of five Australians said they are willing[4] to receive the vaccine. However, at least four out of five are needed to ensure herd immunity[5].

In order to create a sense of urgency among Australians and build trust and confidence in the vaccine, the government may need to look beyond its own public communications campaign[6] to the power of influencers.

After all, if people won’t listen to the government[7], they might just roll up their sleeves if a celebrity is doing the same.

Read more: Just the facts, or more detail? To battle vaccine hesitancy, the messaging has to be just right[8]

The power of celebrity

The power of celebrity has been harnessed in vaccination campaigns[9] many times in the past.

Most famously, Elvis Presley[10] was enlisted to receive his polio vaccine on live television in 1956 as a way of encouraging take-up among teenagers. A group called Teens Against Polio then began its own outreach campaign, which included dances only for the vaccinated. The effort was hugely successful in boosting vaccination rates.

Mothers were another group that were adopting a “wait and see” approach to the polio vaccine. Then, in 1957, Queen Elizabeth announced[11] she had vaccinated her children Prince Charles and Princess Anne, disregarding her usual commitment to keeping her family private.

Queen Elizabeth and Prince Phillip also received their COVID-19 vaccines last month in a bid to counter vaccine hesitancy. The queen had a message[12] for those still on the fence: “they ought to think about other people other than themselves”.

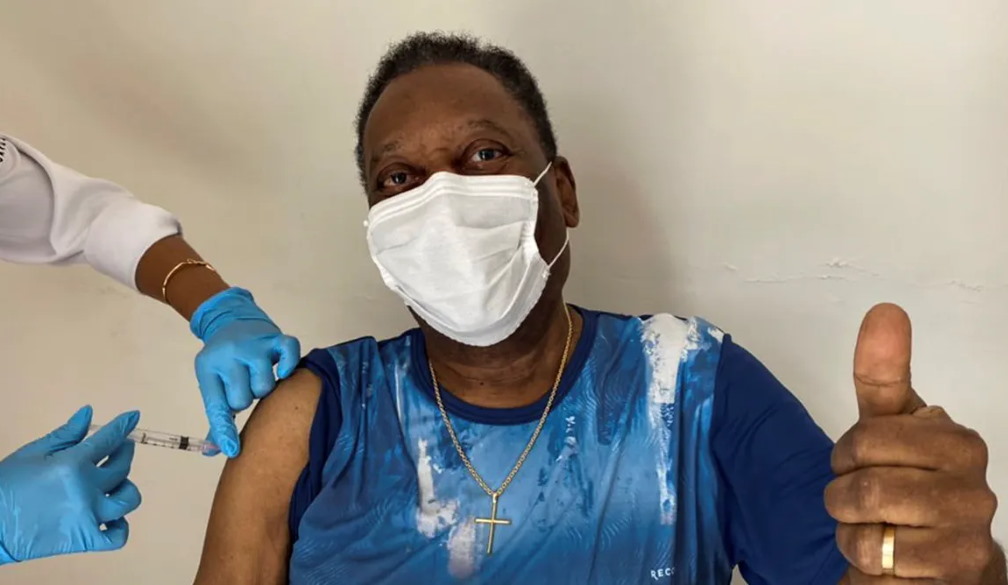

Many other celebrities have also gone public[13] with their COVID vaccines, from Joan Collins to Willie Nelson to Samuel L. Jackson. Politicians, too, have sought to lead by example by receiving their jabs on live television[14].

Celebrity status over science

But does celebrity endorsement always work[15] with public health campaigns, and if so, why?

Research has shown[16] that celebrity endorsements can trigger biological, psychological and social responses in people that make them more trusting[17] of what celebrities say and do, including their endorsement of health information.

It works because the celebrities’ characteristics are transferred[18] to the endorsed products. The most effective celebrity advocates are those viewed as credible — a perception linked to their perceived “success” in life.

People aspire to be like[19] the celebrities they look up to, causing them to behave like them, too. It helps if the celebrities’ advice matches their existing beliefs — an example of confirmation bias[20].

Neuroscience research supports these explanations, finding that celebrity endorsements activate regions in the brain[21] involved in making positive associations, building trust and encoding memories.

Read more: COVID vaccine: celebrity endorsements work – even if people don’t like it[22]

Why vetting of influencers is important

There is ample evidence[23], especially in the social media age, of the power of celebrity endorsements on health issues beyond vaccines.

Kylie Minogue’s public breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, for instance, sparked a 40% rise[24] in breast cancer screenings. And when Magic Johnson announced he was HIV-positive in the early 1990s, a national AIDS hotline reported over 28,000 calls[25] from people wanting more information on HIV/AIDS.

Sometimes, the celebrity effect can backfire. Tennis star Novak Djokovic[26], for instance, was criticised by epidemiologists for making public statements against the COVID vaccination, due to his significant influence in Serbia. Recently, Djokovic has softened his comments, claiming he’s not against vaccines[27] but doesn’t want to be forced to take one.

Celebrity-led health campaigns, if not conducted properly, can also have negative consequences[28].

The federal government received considerable backlash in 2018 for using taxpayer money to hire Instagram influencers to promote its “girls make your move[29]” campaign. It was discovered some of the influencers had made racist remarks or were being paid to promote alcohol brands.

For this reason, careful vetting[30] of the celebrity or influencer is fundamentally important. Their social media reach is swift and significant, which can either amplify the message or blow up into a scandal[31].

Rational arguments and data aren’t enough

But can those who are unsure about COVID vaccines be successfully persuaded? It’s a pertinent and timely question.

Research[32] suggests those who are vehemently dug into their position are unlikely to be persuaded. Those chanting “my body, my choice” at rallies ahead of the vaccine roll-out are likely to be difficult to persuade[33].

Read more: Yeh, nah, maybe. When it comes to accepting the COVID vaccine, it's Australia's fence-sitters we should pay attention to[34]

It’s the malleable middle, those who are merely hesitant[35] about vaccines, the government needs to target with its messages. This is where celebrity or influencer endorsements may help.

For a message to be effective, the use of rational arguments and data alone are not enough. We are persuaded[36] by both the way the message is presented and the messenger (and the desirable attributes we perceive that person to have).

Providing vaccine information on its own might not be enough if it falls on deaf ears.

References

- ^ 54 million doses (www.health.gov.au)

- ^ 20 million doses (www.health.gov.au)

- ^ vaccine hesitancy on the rise (www.news-medical.net)

- ^ said they are willing (www.anu.edu.au)

- ^ herd immunity (theconversation.com)

- ^ own public communications campaign (theconversation.com)

- ^ won’t listen to the government (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ Just the facts, or more detail? To battle vaccine hesitancy, the messaging has to be just right (theconversation.com)

- ^ vaccination campaigns (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ Elvis Presley (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ announced (www.dailymail.co.uk)

- ^ message (www.reuters.com)

- ^ gone public (www.vulture.com)

- ^ on live television (www.cbsnews.com)

- ^ always work (www.bmj.com)

- ^ shown (link.springer.com)

- ^ more trusting (www.emerald.com)

- ^ transferred (www.emerald.com)

- ^ aspire to be like (theconversation.com)

- ^ confirmation bias (www.nature.com)

- ^ activate regions in the brain (link.springer.com)

- ^ COVID vaccine: celebrity endorsements work – even if people don’t like it (theconversation.com)

- ^ evidence (journals.sagepub.com)

- ^ 40% rise (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ reported over 28,000 calls (systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com)

- ^ Tennis star Novak Djokovic (www.espn.com)

- ^ claiming he’s not against vaccines (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ negative consequences (systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com)

- ^ girls make your move (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ careful vetting (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ amplify the message or blow up into a scandal (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ Research (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ persuade (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ Yeh, nah, maybe. When it comes to accepting the COVID vaccine, it's Australia's fence-sitters we should pay attention to (theconversation.com)

- ^ hesitant (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ persuaded (www.sciencedirect.com)