what are preference deals and how do they work?

- Written by Josh Sunman, PhD candidate, Flinders University

In the run up to the federal election, there is growing discussion of “preference deals[1]” between political parties.

But what are preference deals and how do they work?

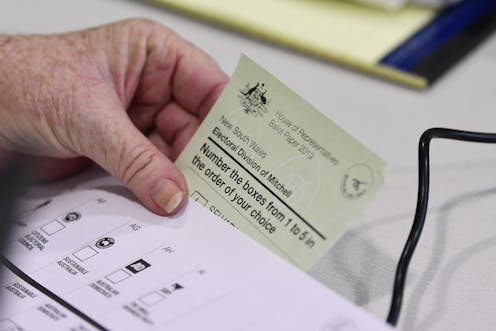

In Australian federal elections, voters fill in ordinal ballots for both the house and the senate. This means voters are required to number the candidates who appear on the ballot paper in order of their preference.

On House of Representatives ballots, voters must number every candidate on the ballot paper. Senate ballots meanwhile, afford voters the choice of numbering at least six party groups in above-the-line voting, or numbering at least 12 individual candidates below-the-line.

In the 151 house electorates, candidates must achieve a vote total of “50% plus one” of valid votes in order to be elected. If no candidate achieves this on their primary vote – the number of votes that preference that candidate first – the preferences of unsuccessful candidates are distributed.

To do this, the candidate with the lowest primary is excluded from the count, and the ballots that preference them first are then allocated according to their second nominated preference. This process continues until a candidate achieves the “50% plus one” required to be elected.

Read more: Explainer: how does preferential voting work in the House of Representatives?[2]

Preferences matter more than they used to

The 2019 federal election saw the continuation of a downward trend in the primary votes of the two major parties. The Coalition and Labor received a combined 74.78% of first preferences in house electorates[3].

This means more than a quarter of voters gave their first preference to a candidate who was not from either of the major parties.

While the major parties still won 145 of the 151 lower house seats, a record 105 seats had to be decided on preferences. In 12 of these, candidates that were behind on primary votes overtook the person with the most primary votes and reached 50% plus one on the basis of preferences[4].

Preferences are becoming more decisive in how MPs are elected, and which governments are formed.

In the UK, Canada and the US, the candidates who achieve the most primary votes win their seat. In Australia, a candidate with fewer initial votes can be elected, if the preferences “flow” to them.

The key difference here is between majoritarian and plurality electoral systems. In Australia, preferential voting operates on a majoritarian principle of representation. It does not elect the candidate most preferred by the plurality of people; rather, elects a representative who wins more votes than all other candidates combined[5].

Where the deals come in

With more seats being decided on preferences, where parties direct their preferences is naturally receiving more attention. Analysis[6] by the ABC’s election analyst, Antony Green, shows 82.2% of Greens preferences flowed to the Labor party, while the Coalition received approximately 65% of One Nation and United Australia Party preferences.

There is an accepted narrative that parties direct preferences through clandestine deals. It is true senior party officials meet with each other to iron out preference recommendations, but these deals do not actually have any power over votes.

Instead, these deals are merely agreements about which preferences political parties recommend to voters on their distributed how-to-vote material.

For the deals to work, parties require volunteers to distribute how-to-vote cards on polling day, as well as postal and online material. Voters then have to follow the material in order for these published recommendations to have effect.

Since the 1960s, there has been a steady decline in voters reporting they used “how-to-vote” cards. At the 2019 election, it was a record low of just 29% of voters[7].

Read more: So, how did the new Senate voting rules work in practice?[8]

However, preference recommendations can still have an impact. In the 2018 South Australian election, the Liberal and Labor parties, facing the threat of an insurgent campaign from the Nick Xenophon-led SA-Best party, broke with long standing practice and recommended their voters preference each other in crucial seats, in order to prevent a third-party breakthrough.

The “party controls preferences” narrative does have some historical truth to it.

Under the previous Senate voting system, voters had the option of simply voting one above the line. If voters took this option, their vote would then be distributed according to party lodged preference tickets – essentially controlling what happened to voter preferences.

This had a huge impact on electoral outcomes, as in the 2013 election (the last held under this system), when 96.5% of voters took this option[9] .

The 2013 result had some undemocratic outcomes, with Ricky Muir from the Australian Motoring Enthusiasts Party winning one of Victoria’s Senate seats on just 0.5% of the above-the-line vote.

This victory was orchestrated by Glenn Druery, dubbed the “preference whisperer[10]”, who arranged preference swaps between micro parties with microscopic vote totals. These then cascaded to deliver Muir the seat.

This result drew scrutiny to above-the-line Senate voting, leading to reforms[11] that abolished preference tickets, and gave more power to voters to direct their preferences conveniently.

Despite the preference deals, it is ultimately the voters who maintain control over which parties receive their preferences.

References

- ^ preference deals (thewest.com.au)

- ^ Explainer: how does preferential voting work in the House of Representatives? (theconversation.com)

- ^ combined 74.78% of first preferences in house electorates (results.aec.gov.au)

- ^ on the basis of preferences (press-files.anu.edu.au)

- ^ than all other candidates combined (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Analysis (antonygreen.com.au)

- ^ low of just 29% of voters (australianelectionstudy.org)

- ^ So, how did the new Senate voting rules work in practice? (theconversation.com)

- ^ when 96.5% of voters took this option (www.aec.gov.au)

- ^ preference whisperer (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ reforms (www.aph.gov.au)

Read more https://theconversation.com/explainer-what-are-preference-deals-and-how-do-they-work-180140