How the Coalition can win the 2022 election

- Written by Mark Kenny, Professor, Australian Studies Institute, Australian National University

This piece is the second in a two-part series. Its companion piece, How Labor can win the 2022 election, can be found here[1].

When the counting’s done, elections obey the iron laws of arithmetic. Yet, in the lead-up to polling day, psychology also plays its part.

At two key federal elections in living memory, the upset winner relied on more malleable things than hard numbers to leaven their poor electoral prospects – unquantifiables such as hope, self-belief, even faith.

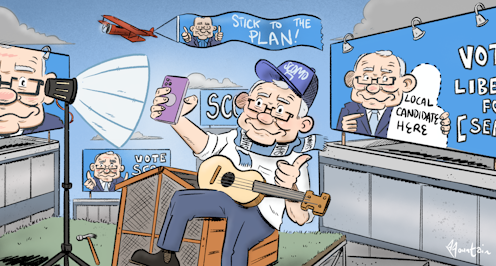

Paul Keating’s “victory for the true believers” in 1993, and Scott Morrison’s “miracle win” in 2019, stand out as elections during which the leaders successfully harnessed these most human of motivations.

Each had used them not merely to steel themselves against a corrosive defeatism to which they might have otherwise succumbed, but also to project that confidence within their inner circle and outwards to their wider base. This “build it and they will come” mindset assisted them to beat the odds and ultimately prevail.

Crucially, both campaigns were designed to give tired governments another term against fresher, if more radical, alternatives: John Hewson’s super-specific Fightback manifesto in 1993, and in 2019, Bill Shorten’s comprehensive tax-and-spend plans.

In 2022, though, Morrison faces a tougher task.

First, he’s already pulled off a stealth victory once, and Anthony Albanese has taken clear lessons from that shock. The Labor leader is determined to make election 2022 a referendum on the government’s failures and not, as it became in 2019, a fear-fight about the opposition’s policy plans. Expect Albanese to direct the spotlight relentlessly at the prime minister himself.

Second, Morrison’s advantage in 2019 was that voters didn’t know him well, which allowed the former marketing executive to fill in the gaps.

Cunningly, he presented as a kind of competent accountant who was reassuringly dull. It worked precisely because he was so unthreatening – a politician, yes, but one who was also a suburban everyman. Voters felt little desire to know more.

Three years later though, they do. They see a polarising figure known for blame-shifting, despised by some who have worked with him closely, and described as deceitful, overbearing and ruthless.

Third, the Coalition is probably further behind in 2022.

Yet, for all this, Morrison has told his colleagues he will win, and few doubt his belief. So, is a fourth term possible? Yes, if Morrison succeeds in keeping the focus on his ground - the economy and national security - enabling him to retain the seats the Coalition holds in net terms.

That won’t be easy, given Labor’s eight-point two-party lead and the fact that Morrison is just one point ahead in the most recent Newspoll’s better PM index.

Read more: Coalition and Greens gain in post-budget Newspoll as an Ipsos poll gives Labor a large lead[2]

Yet, as Morrison has told his colleagues, Labor’s path to a majority is more difficult. It’s harder still if you price in the usual narrowing of opinion polls at the business end of this race.

In raw seats, Morrison starts ahead, with 76 in the 151-member house to Labor’s 69. The opposition needs to hold what it has and gain seven to govern in its own right.

Queensland might be the birthplace of the ALP and friendly ground for Labor’s Annastacia Palaszczuk, but it is hardly propitious for federal Labor. Out of 30 House of Representatives seats, Labor holds just six, and has no great confidence in picking up more.

That said, the veteran Liberal Warren Entsch (Leichhardt) admits the slow responses to the floods and the pandemic have left Far North Queensland voters angry, with some now drifting rightward towards populists Clive Palmer and Pauline Hanson.

In the Northern Territory it is probably status quo also, although Liberals think Lingiari (5.5%) is “gettable” after the retirement of Labor stalwart Warren Snowden. Solomon (3.1%) is also mentioned.

So what about resource-rich Western Australia? Here, Morrison could live or die. Labor is optimistically eyeing five seats but if by some strange “miracle” Liberals hang on to all of them, Morrison would be a long way towards retaining government. Yet going into the campaign, that looks unlikely.

Labor is campaigning hard in Pearce, which has been vacated by Christian Porter and is likely to snare the 5.2% electorate given Porter’s infamy and the shredded Liberal brand in the West.

The next most likely are Swan and Hasluck. The former is being vacated by a retiring Liberal MP Steve Irons. At just 3.2%, it too is a probable Liberal loss. Hasluck, however, held by the respected Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt, would take a 6% Labor swing to change hands.

Moving east, the recent rout of the Liberal state government in South Australia suggests the blue-ribbon jewel of Boothby (1.4%) will fall. But that could easily be the extent of damage in the ten-seat central state. That said, state voting booth-by-booth, if applied to federal boundaries suggests Sturt at 6.9% is also vulnerable.

In Victoria, Labor’s support was high at the last election, which means there are few Labor prospects in 2022 aside from Chisholm (0.5%). However, the Liberal party is under threat in several heartland seats with “teal” independents pushing hard in Higgins, Kooyong and Goldstein.

In New South Wales, Morrison expects to regain Gilmore via a popular ex-state MP for the area, Andrew Constance. In a best-case scenario, the biggest state would otherwise remain fairly static. Still, a squalid factional brawl has left key electoral prospects without Liberal candidates until the death knell. Plus, Liberal seats like Reid (3.2%) and Robertson (4.2%) remain extremely vulnerable.

Liberals say an against-the-play gain in Tasmania is possible, with Morrison eyeing an upset in Labor-held Lyons (5.1%). But the party could also fall short and lose Bass as well, which it holds by a wafer-thin 0.4%.

In the end, all this detail could be swept aside if the electorate is of a clear mind to change government. As they say in political circles, when a swing is on, it’s on.

Read more: Want to understand how the Coalition works? Take a look at climate policy[3]

Nevertheless, Morrison could actually survive a sizeable swing in some areas if he can pick up the odd win here and there to offset losses.

Of course, the wildcard is the rise of the independents. Their success in Liberal strongholds such as Wentworth, Goldstein, Higgins and Curtin could see the Coalition displaced even if Labor falls short of its own majority. And defending these seats will cost money and resources.

After nearly a decade in office, the Coalition carries plenty of scar tissue into this contest, and Morrison himself has attracted extraordinary personal criticism on character grounds - largely from his own side.

Yet he is an ebullient and disciplined campaigner who has shown how to carry a message, dismantle those of his opponents, and frighten voters.

In 2019, voters didn’t need to like him to stick with the status quo. He’ll be hoping that in 2022, his perceived strengths on jobs, economic growth, and national security, will outweigh his low standing personally.

And who knows? Surely that’s the key lesson of 2019 for both sides: it’s not over until it’s over. Morrison believes this even if others have their doubts.

References

- ^ here (theconversation.com)

- ^ Coalition and Greens gain in post-budget Newspoll as an Ipsos poll gives Labor a large lead (theconversation.com)

- ^ Want to understand how the Coalition works? Take a look at climate policy (theconversation.com)

Read more https://theconversation.com/how-the-coalition-can-win-the-2022-election-179942