Australia's stubborn growth problems are moving at a geologic pace

- Written by Richard Holden, Professor of Economics and PLuS Alliance Fellow, UNSW

Vital Signs is a regular economic wrap from UNSW economics professor and Harvard PhD Richard Holden (@profholden). Vital Signs aims to contextualise weekly economic events and cut through the noise of the data affecting global economies.

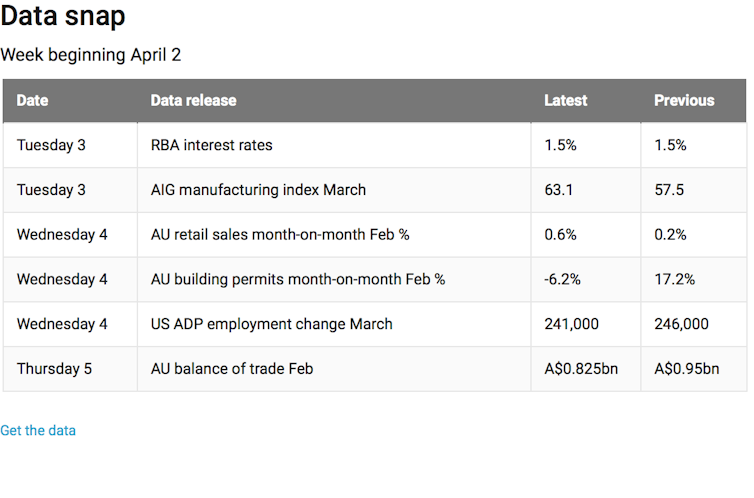

This week: Interest rates remain on hold as the RBA talks up employment growth, green shoots remain in manufacturing, and China strikes back in the Trump-led trade war.

On Tuesday, the RBA left official interest rates unchanged at 1.50% for the 18th consecutive meeting, tying their all-time record. They will break that record next month when they do the same thing.

And the official statement[1] by governor Philip Lowe sounded like it came from a guy who had gone from crossing his fingers to crossing his toes as well. For example:

“The Australian economy grew by 2.4 per cent over 2017. The Bank’s central forecast remains for faster growth in 2018.”

Um, why? The same macro model that got 2017 wrong is now going to get 2018 right?

Or this one:

“The unemployment rate has declined over the past year, but has been steady at around 5½ per cent over the past six months. The various forward-looking indicators continue to point to solid growth in employment in the period ahead, with a further gradual reduction in the unemployment rate expected.”

But a few months ago, those same forward-looking indicators were saying the plateau in the unemployment rate wouldn’t happen.

And finally (but only because I have space constraints):

“Notwithstanding the improving labour market, wages growth remains low. This is likely to continue for a while yet, although the stronger economy should see some lift in wages growth over time.”

If “over time” is read analogous to “life in the Mesazoic Era evolved over time” then I suppose that may be right.

Unfortunately for the RBA, the health of the economy is not measured on the Geologic Time Scale. Stubbornly low inflation, persistently hopeless wage growth, and with the Australian population growing at 1.6% p.a.[2], that 2.4% GDP growth number looks pretty weak. The real question is whether the RBA is not cutting rates because it thinks monetary policy is ineffective at this level, or because it’s scared of fuelling (further fuelling?) a (the?) housing price bubble.

Read more:

What economics has to say about housing bubbles[3]

ABS data[4] released Wednesday showed a drop in building approvals in February. Total dwelling approvals were down 6.2%, driven by a 16.4% drop in apartments, compared to a 1.9% rise in houses. For the 12 months to February 2018, that puts the total down 3.1%, again driven by a large (14.8%) drop in apartments and a rise (6.1%) in houses.

This is all evidence that demand – often from offshore – has dried up in one important sector of the market: apartments. It is still too early to know what the fallout will be, but this is exactly the kind of pattern one sees in property markets when the music has stopped.

The Australian Industry Group’s Performance of Manufacturing Index[5], released this week, hit a record high of 63.1 index points for March. Perhaps more importantly, the survey indicated that capacity utilisation was at a record high of 81.2%. This matters because it suggests stronger employment and wage growth in the sector.

On the other hand, manufacturing is about 6.5% of GDP, so even strong growth in the sector has a relatively modest overall effect. But, as they say in baseball, you can’t boo a home run.

US jobs figures continued to impress, with payroll processor ADP releasing figures Thursday Australian time that the economy added 241,000 jobs in March. The official figures from the BEA come out Friday US time, with market expectations at an addition of 185,000. So if the official figures line up with ADP, this will be further evidence of strong employment growth.

This week, China struck back, again. The Trump administration recently instituted roughly US$50 billion worth of tariffs on steel, cars, automotive and aircraft parts, consumer products like televisions, and other goods. Almost immediately, China responded with tariffs of a similar value on 106 types of American goods.

Read more:

America's allies will bear the brunt of Trump's trade protectionism[6]

Those 106 types of goods include soybeans and others produced in the Trump heartland. This was a cleverly designed, targeted measure, designed to hurt Trump politically.

His response:

That reveals his mercantilist view of trade: that it’s a zero-sum game rather than something that increases the size of the economic pie and makes both countries better off. But hey, maybe he has a big reading backlog and isn’t up to 1817, when David Ricardo pointed this out with his theory of “comparative advantage”[7].

Let’s hope it does, and President Trump gets the message that he needs to knock this off. All he is doing is making America poorer. And the game theory of it is worse. Tariffs beget tariffs.

On Tuesday, the RBA left official interest rates unchanged at 1.50% for the 18th consecutive meeting, tying their all-time record. They will break that record next month when they do the same thing.

And the official statement[1] by governor Philip Lowe sounded like it came from a guy who had gone from crossing his fingers to crossing his toes as well. For example:

“The Australian economy grew by 2.4 per cent over 2017. The Bank’s central forecast remains for faster growth in 2018.”

Um, why? The same macro model that got 2017 wrong is now going to get 2018 right?

Or this one:

“The unemployment rate has declined over the past year, but has been steady at around 5½ per cent over the past six months. The various forward-looking indicators continue to point to solid growth in employment in the period ahead, with a further gradual reduction in the unemployment rate expected.”

But a few months ago, those same forward-looking indicators were saying the plateau in the unemployment rate wouldn’t happen.

And finally (but only because I have space constraints):

“Notwithstanding the improving labour market, wages growth remains low. This is likely to continue for a while yet, although the stronger economy should see some lift in wages growth over time.”

If “over time” is read analogous to “life in the Mesazoic Era evolved over time” then I suppose that may be right.

Unfortunately for the RBA, the health of the economy is not measured on the Geologic Time Scale. Stubbornly low inflation, persistently hopeless wage growth, and with the Australian population growing at 1.6% p.a.[2], that 2.4% GDP growth number looks pretty weak. The real question is whether the RBA is not cutting rates because it thinks monetary policy is ineffective at this level, or because it’s scared of fuelling (further fuelling?) a (the?) housing price bubble.

Read more:

What economics has to say about housing bubbles[3]

ABS data[4] released Wednesday showed a drop in building approvals in February. Total dwelling approvals were down 6.2%, driven by a 16.4% drop in apartments, compared to a 1.9% rise in houses. For the 12 months to February 2018, that puts the total down 3.1%, again driven by a large (14.8%) drop in apartments and a rise (6.1%) in houses.

This is all evidence that demand – often from offshore – has dried up in one important sector of the market: apartments. It is still too early to know what the fallout will be, but this is exactly the kind of pattern one sees in property markets when the music has stopped.

The Australian Industry Group’s Performance of Manufacturing Index[5], released this week, hit a record high of 63.1 index points for March. Perhaps more importantly, the survey indicated that capacity utilisation was at a record high of 81.2%. This matters because it suggests stronger employment and wage growth in the sector.

On the other hand, manufacturing is about 6.5% of GDP, so even strong growth in the sector has a relatively modest overall effect. But, as they say in baseball, you can’t boo a home run.

US jobs figures continued to impress, with payroll processor ADP releasing figures Thursday Australian time that the economy added 241,000 jobs in March. The official figures from the BEA come out Friday US time, with market expectations at an addition of 185,000. So if the official figures line up with ADP, this will be further evidence of strong employment growth.

This week, China struck back, again. The Trump administration recently instituted roughly US$50 billion worth of tariffs on steel, cars, automotive and aircraft parts, consumer products like televisions, and other goods. Almost immediately, China responded with tariffs of a similar value on 106 types of American goods.

Read more:

America's allies will bear the brunt of Trump's trade protectionism[6]

Those 106 types of goods include soybeans and others produced in the Trump heartland. This was a cleverly designed, targeted measure, designed to hurt Trump politically.

His response:

That reveals his mercantilist view of trade: that it’s a zero-sum game rather than something that increases the size of the economic pie and makes both countries better off. But hey, maybe he has a big reading backlog and isn’t up to 1817, when David Ricardo pointed this out with his theory of “comparative advantage”[7].

Let’s hope it does, and President Trump gets the message that he needs to knock this off. All he is doing is making America poorer. And the game theory of it is worse. Tariffs beget tariffs.

References

- ^ official statement (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ Australian population growing at 1.6% p.a. (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ What economics has to say about housing bubbles (theconversation.com)

- ^ ABS data (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ Performance of Manufacturing Index (www.aigroup.com.au)

- ^ America's allies will bear the brunt of Trump's trade protectionism (theconversation.com)

- ^ “comparative advantage” (www.investopedia.com)

Authors: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics and PLuS Alliance Fellow, UNSW