Australia has truly excellent food security

- Written by Steve Hatfield-Dodds, Executive Director, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES)

COVID-19 has taken Australia and the world by surprise. Coming after severe droughts in eastern Australia, concerns have been raised about Australian food security.

The concerns are understandable, but they are misplaced.

Despite temporary shortages of some food items in supermarkets caused by an unexpected surge in demand, Australia does not have a food security problem.

An Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences study[1] released today outlines why Australia is one of the most food-secure countries in the world.

Supermarket shelves reflect a surge in demand

Uncertainties around the impacts of COVID-19 have triggered a rapid increase in purchasing by consumers seeking to stockpile a range of items, resulting in disruption to stocks of some basic food items.

This disruption is temporary and not an indication of food shortages.

Rather, it is a result of logistics[2] taking time to adapt to an unexpected surge in purchasing.

We are highly food-secure

Food security refers to the physical availability of food, and to whether people have the resources and opportunity to get reliable economic access to it.

Australia ranks among the most food secure nations in the world, and is in the top 10 countries[3] for food affordability and availability.

Australians are wealthy by global standards and can choose from diverse and high-quality foods from all over the world at affordable prices.

Most Australians can afford to purchase healthy food that meets their nutritional needs, and as a result, Australia has the world’s equal-lowest level of undernourishment.

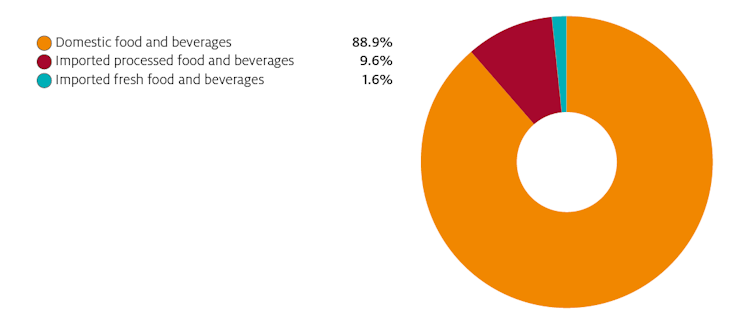

We import only 11% of our food

Most food and beverages consumed in Australia are produced in Australia.

But not everything that Australians like to eat is produced here. So we import about 11% of the food and beverages we consume by value.

The imports are mainly processed products (including coffee beans, frozen vegetables, seafood products, and beverages), along with small amounts of out-of-season fresh food.

Imported products account for 11% of expenditure on food and beverages

Imports of processed and fresh (primary) food and beverages, as a share of total food and beverage consumption (including tobacco and alcohol) by value, three year average 2016-17 to 2018-19. Does not include takeaway and restaurant meals.

ABS 5368.0, 5204.0[4]

Imports of processed and fresh (primary) food and beverages, as a share of total food and beverage consumption (including tobacco and alcohol) by value, three year average 2016-17 to 2018-19. Does not include takeaway and restaurant meals.

ABS 5368.0, 5204.0[4]

It is possible that disruptions to food imports from COVID-19 (or something else) could result in temporary shortages of some products, restricting consumer choice in the same way as cyclones have restricted access to Australian bananas.

It would be unlikely to have a material impact on food security – in terms of ensuring a sufficient supply of healthy and nutritious food, even if higher prices for or limited availability of specific products disappoints or inconveniences some consumers.

Australia produces more food than it consumes

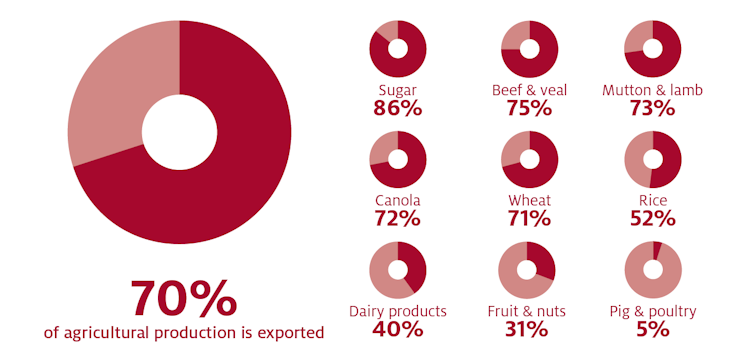

Australia typically exports about 70% of agricultural production.

The level of exports varies across sectors. Some of our largest industries, such as beef and wheat, are heavily export-focused. Others, like horticulture, pork and poultry, sell most of their products in Australia, with an emphasis on supplying fresh produce.

Most Australian agricultural production is export oriented

Share of agricultural production exported by sector, 3 year average, 2015-16 to 2017-18.

Source: ABARES 2020[5]

Share of agricultural production exported by sector, 3 year average, 2015-16 to 2017-18.

Source: ABARES 2020[5]

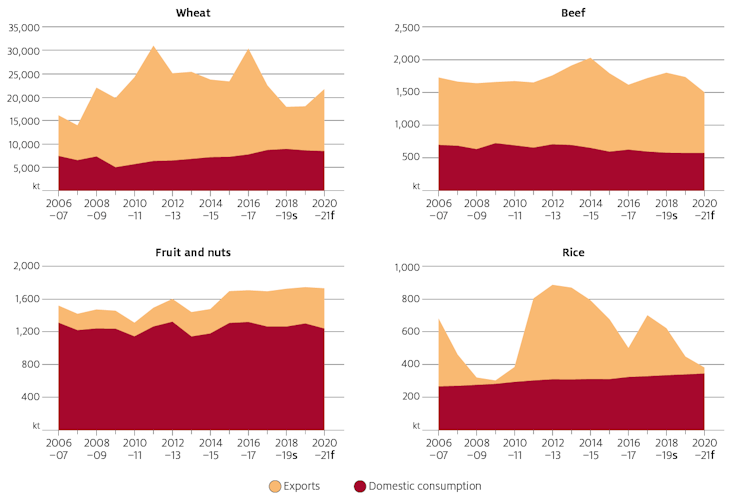

Australia’s large exports, even in severe drought years, act as a shock absorber for domestic supply.

They allow domestic consumption to remain stable while exports vary, absorbing the ups and downs associated with Australia’s variable climate and seasonal conditions.

Domestic food consumption is stable, while agricultural exports vary

Domestic consumption and export estimates for wheat, beef, rice, fruit and nuts, 2006-07 to 2020-21. Fruit and nuts covers table grapes, apples, pears, oranges, mandarins, peaches, mangoes, bananas, almonds and macadamias. f = forecast.

Source: ABARES 2020[6]

Domestic consumption and export estimates for wheat, beef, rice, fruit and nuts, 2006-07 to 2020-21. Fruit and nuts covers table grapes, apples, pears, oranges, mandarins, peaches, mangoes, bananas, almonds and macadamias. f = forecast.

Source: ABARES 2020[6]

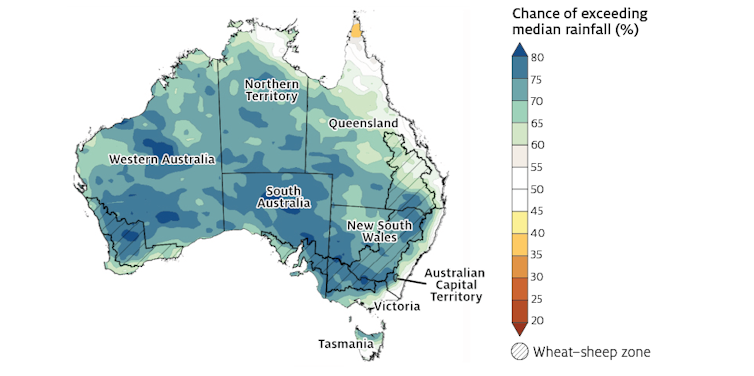

The outlook for rain is good

After a hot and dry 2019 and widespread drought conditions in NSW and Queensland, above-average recent rains and positive forecasts[7] provide the basis for the best start to Australia’s agricultural production season in years.

While current prospects for winter crops are good, more rain is required for these to be realised.

The Bureau is forecasting that grain production is likely to return to close to average levels, with a significant chance of higher production given the good start to the winter cropping season.

Wetter than average conditions are likely across agricultural areas from May to July 2020

Map shows chance of exceeding median rainfall for the period May to July 2020, showing above average rainfall is likely or very likely across all inland areas of Australia, including the wheat sheep zone.

Source: BOM, April 9, 2020[8]

Map shows chance of exceeding median rainfall for the period May to July 2020, showing above average rainfall is likely or very likely across all inland areas of Australia, including the wheat sheep zone.

Source: BOM, April 9, 2020[8]

For livestock producers, better seasonal conditions provide the opportunity to rebuild herds and flocks following a relatively long period of destocking.

Our access to food is secure

Australia is one of the most food-secure countries in the world, with ample supplies of safe, healthy food. The vast majority of it is produced here in Australia, and domestic production more than meets our needs, even in drought years.

While we import about 11% of our food and beverages, disruptions to these imports would not threaten the food security of most Australians.

The Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences is forecasting a return to close to average levels of grain production, with a significant chance of higher production, given the good start to the winter cropping season.

Read more: Helping farmers in distress doesn't help them be the best: the drought relief dilemma[9]

The analysis released today[10] explores related issues in more depth, including the contribution of irrigated agriculture to Australian food security, levels of global grain stocks, and the contributions of international trade and Australian exports to food security in other countries.

Australia’s agricultural producers do rely on global supply chains and imported inputs. Shortages or disruptions to these inputs have not yet been significant or widespread, but could reduce productivity and profitability.

While action is already in train to address key issues, it will be important for business and government to continue actively monitoring and managing these risks.

References

- ^ study (www.agriculture.gov.au)

- ^ logistics (www.investopedia.com)

- ^ top 10 countries (foodsecurityindex.eiu.com)

- ^ ABS 5368.0, 5204.0 (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ Source: ABARES 2020 (www.agriculture.gov.au)

- ^ Source: ABARES 2020 (www.agriculture.gov.au)

- ^ positive forecasts (www.bom.gov.au)

- ^ Source: BOM, April 9, 2020 (www.bom.gov.au)

- ^ Helping farmers in distress doesn't help them be the best: the drought relief dilemma (theconversation.com)

- ^ analysis released today (www.agriculture.gov.au)

Authors: Steve Hatfield-Dodds, Executive Director, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES)

Read more https://theconversation.com/dont-panic-australia-has-truly-excellent-food-security-136405