Tim Fischer had his blind spots, but he was an unsung champion of an Asian-facing Australia

- Written by Tim Harcourt, J.W. Nevile Fellow in Economics and host of The Airport Economist, UNSW

Amid the tributes to former deputy prime minister Tim Fischer and the stories of his authenticity, courage and quirky interests – like trains[1] and military history – what has struck me most are the examples of his personal kindness.

Read more: Tim Fischer – a man of courage and loyalty – dies from cancer[2]

One of those stories is how Fischer helped a desperate Laotian refugee[3] who in 1986 pulled a gun at the Immigration office in Albury, near Fischer’s office. It turned into a siege. Fischer walked in alone and defused the situation. He then travelled to Thailand in an attempt to get the man’s family out of the refugee camp in which they were stuck.

There are many similar stories – from army mates, farmers, journalist and politicians of all parties. I experienced Fischer’s personal kindness several times.

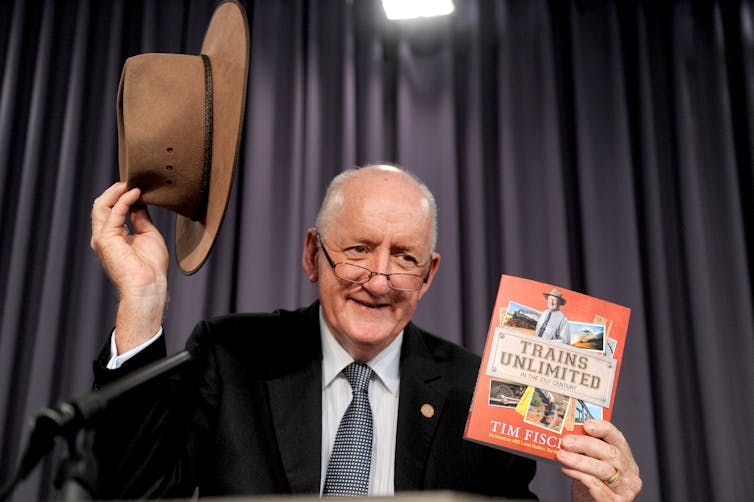

Tim Fischer with his book ‘Trains Unlimited in the 21st century’. Fischer had six books published, three of them about trains.

Alan Porritt/AAP

Tim Fischer with his book ‘Trains Unlimited in the 21st century’. Fischer had six books published, three of them about trains.

Alan Porritt/AAP

Austrade memories

The first was when I was appointed chief economist at Austrade in 1999. That made Fischer, who was the federal trade minister as well as deputy prime minister, my boss.

My appointment was heavily criticised in The Australian newspaper – presumably because my previous job was with the Australian Council of Trade Unions. It called my appointment “payback” for Fischer’s chief of staff, Craig Symon, getting a senior executive role at Austrade.

I was a bit worried. But then I got a phone call from Fischer. “You got the job on your abilities as an economist,” he said to me. “If you get any political crap, let me know.”

Austrade staff loved working for Fischer. Every time he made a speech at a public event, he would single out an Austrade employee and recall something good they had done. It it made the person feel like a million bucks.

The second was when my book The Airport Economist[4] was published, in 2008. Fischer took a copy to Thailand and gave it to the Thai prime minister, Abhisit Vejjajiva, an avid reader of economic literature.

At a later APEC summit, when world leaders were asked their favourite book, Abhisit replied: “The Airport Economist.” Straight away the Bangkok Post published the book in the Thai language. We had a book launch at the Bangkok Stock Exchange with Australia’s Ambassador to Thailand and Thai TV anchor Rungthip Chotnapalai. The book became a best seller in Thailand, all thanks to Fischer.

Tim Fischer (in doorway) watches a re-enactment of the Kelly Gang holding up the Glenrowan train in June 2008. The steam train was making its final journey along the broad-gauge track between Seymour and Albury in Victoria.

Paddy Milne/AAP

Tim Fischer (in doorway) watches a re-enactment of the Kelly Gang holding up the Glenrowan train in June 2008. The steam train was making its final journey along the broad-gauge track between Seymour and Albury in Victoria.

Paddy Milne/AAP

An unsung hero of Asian engagement

Fischer is in many ways the unsung hero of Australia’s changed attitudes to Asia in the 20th century. Labor’s legends Gough Whitlam, Bob Hawke and Paul Keating are all known for championing Asian economic engagement. But Fischer also played a huge role in cementing relationships. He laid his Akubra hat on negotiating tables in most of Asia’s capitals, spruiked deals and hammered out treaties.

A veteran of the Vietnam war, his army days no doubt affected how he thought Australia should view our neighbours. His passion for improved ties with Asia generally, not just in trade, was genuine and authentic. He loved Thailand and Bhutan in particular.

He was in some ways, part of a tradition of Country/National party leaders who pushed Australia towards Asia, largely for economic reasons. For example, John “Black Jack” McEwen negotiated the Commerce Agreement with Japan[5] in 1957, just 12 years after World War II. In the 1970s, Doug Anthony also championed our interests in Asia. Fischer similarly saw Asia as “Our Near North” rather than that quaint old term “The Far East”.

Fischer had his blind spots, to be sure. He failed to appreciate the High Court’s Mabo and Wik decisions, for example. He was a sucker for conspiracy theories at times. But you can’t have everything.

Tm Fischer joins National Disability Insurance Scheme campaigners outside Parliament House in 2012.

Alan Porritt?AAP

Tm Fischer joins National Disability Insurance Scheme campaigners outside Parliament House in 2012.

Alan Porritt?AAP

His political career was long, beginning with election to the New South Wales parliament at age 24. But his ministerial career was quite short – just three years. In 1999 he quit his ministerial posts, and the leadership of the National Party, to spend more time to his family – especially his son Harrison, then aged five, who had been diagnosed with autism.

But the impression Fischer made makes it seem he spent much longer at the top. He was like cricketer Mike Whitney and rugby union player Peter Fitzsimmons. Neither played many tests for Australia but they sure leveraged that time into successful subsequent careers. Fischer did the same.

Now the train has finally left the station.

References

- ^ trains (www.theaustralian.com.au)

- ^ Tim Fischer – a man of courage and loyalty – dies from cancer (theconversation.com)

- ^ Fischer helped a desperate Laotian refugee (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ The Airport Economist (www.allenandunwin.com)

- ^ Commerce Agreement with Japan (www.aph.gov.au)

Authors: Tim Harcourt, J.W. Nevile Fellow in Economics and host of The Airport Economist, UNSW