Amid talk of recessions, our progress on wages and unemployment is almost non-existent

- Written by Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

Legend has it that, when asked by US President Richard Nixon in 1972 what he thought about the impact of the French Revolution, Chinese Premier Zhou En Lai replied: “it’s too early to say”.

Waiting for progress on wages and unemployment in Australia may not be a multi-century enterprise (the French Revolution was in 1789) but Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe’s testimony[1] to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics on Friday was reminiscent of Zhou’s caution:

In the central scenario that I have sketched today, inflation will be below the target band for some time to come and the unemployment rate will remain above the level we estimate to be consistent with full employment.

While this remains the case, the possibility of lower interest rates will remain on the table. The board is prepared to ease monetary policy further if there is additional accumulation of evidence that this is needed to achieve our goals of full employment and inflation consistent with the target. Time will tell.

That was a week ago, but since then “old man time[2]” has given us two less than completely encouraging pieces of information.

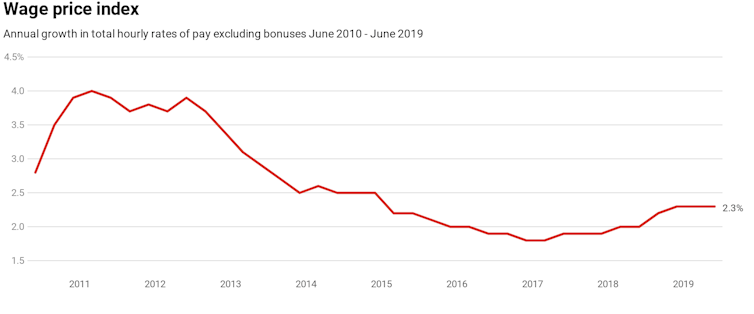

Wage growth isn’t really climbing

On Wednesday the Bureau of Statistics released the June quarter Wage Price Index[3] which showed wages rising 0.6% for the quarter and 2.3% on the year.

It provides two things to worry about.

First, wage growth isn’t rising. Annual growth has remained unchanged for three quarters.

ABS 6345.0[4]

Second, the growth that is there is driven more by the public sector (0.8% over the quarter) than the private sector (0.5%).

As the Bureau’s chief economist Bruce Hockman puts it

Wage growth continues at a steady rate in the Australian economy on the back of strong public sector growth over the quarter. The most significant contribution to wage growth this quarter came from the public sector component of the health care and social assistance industry, where a number of large increases were recorded in Victoria under a plan to ensure wage parity with other states.

Things might improve when and if the Reserve Bank interest rate cuts of June 5 and July 2 start changing the way consumers and employers think.

But the Reserve Bank cash rate has been at a record low of 1.5% since September 2016. All through those three years Governor Lowe has told us to be patient, that soon wage growth will climb and unemployment will fall.

We’ve had little progress on wages, and since January none on unemployment.

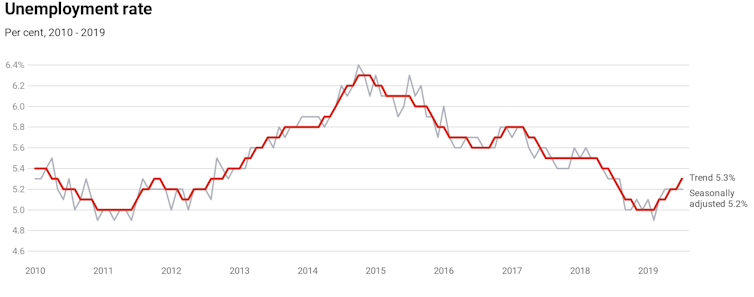

Unemployment isn’t really falling

On Thursday the bureau followed up with the latest unemployment figures[5].

Although job creation was strong in July – 24,600 jobs were added to the economy, 15,100 of which were full-time – the trend unemployment rate ticked up to 5.3%, from 5.2%.

The “trend” is a smoothed out extension of the way the way the Bureau of Statistics algorithm thinks the rate is going.

ABS 6345.0[4]

Second, the growth that is there is driven more by the public sector (0.8% over the quarter) than the private sector (0.5%).

As the Bureau’s chief economist Bruce Hockman puts it

Wage growth continues at a steady rate in the Australian economy on the back of strong public sector growth over the quarter. The most significant contribution to wage growth this quarter came from the public sector component of the health care and social assistance industry, where a number of large increases were recorded in Victoria under a plan to ensure wage parity with other states.

Things might improve when and if the Reserve Bank interest rate cuts of June 5 and July 2 start changing the way consumers and employers think.

But the Reserve Bank cash rate has been at a record low of 1.5% since September 2016. All through those three years Governor Lowe has told us to be patient, that soon wage growth will climb and unemployment will fall.

We’ve had little progress on wages, and since January none on unemployment.

Unemployment isn’t really falling

On Thursday the bureau followed up with the latest unemployment figures[5].

Although job creation was strong in July – 24,600 jobs were added to the economy, 15,100 of which were full-time – the trend unemployment rate ticked up to 5.3%, from 5.2%.

The “trend” is a smoothed out extension of the way the way the Bureau of Statistics algorithm thinks the rate is going.

ABS 6202.0[6]

In part it is going up because more people not previously regarded as unemployed are looking for work (and not finding it).

It isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but it is also exactly what would be expected when wage growth was sluggish. Households are doing what they can to assemble more income.

The world economy is in trouble

Global economic conditions are concerning. This week Eurpoe’s second-biggest economy Germany[7] announced that its economy shrank by 0.1% in the second quarter of 2019, putting it on track to meet what some people call the technical definition of a recession.

Figures out of China regarding industrial production were also worrying, with factory output climbing more slowly than at any time in the last 17 years.

The US stock market climbed 1.5% on Tuesday after the Trump administration announced it would delay some of its new tariffs on China, but slid twice that amount the next day on the news from Germany and China.

Read more:

Are Trump's tariffs legal under the WTO? It seems not, and they are overturning 70 years of global leadership[8]

The fall in stocks led to a flight to the relative safety of government bonds. This caused the yield on 10 year US government bonds to fall below that of the 2 year bonds, a so-called “inverted yield curve” of the kind usually seen before a recession. The last time the US yield curve inverted was before the US Great Recession of 2008.

None of this is good for Australia. With roughly 20% of our economy powered by exports, we need the countries we export to to be doing well.

As Reserve Bank deputy governor Guy Debelle put it in a speech[9] on Thursday

Australia also has significant exports to China in both tourism and education. To date, these have been broadly unaffected by the slowdown in the Chinese economy. But a further significant slowing in the Chinese economy and household incomes would clearly pose a risk.

There’s no telling how low rates will go

There have been plenty of competing views[10] about the state of the Australian economy over the past few years.

Not long ago most economists who thought interest rates would move thought they would rise[11]. The Reserve Bank governor suggested the same.

But its increasingly clear that secular stagnation[12] is gripping advanced economies around the world. In response, the US Federal Reserve has recommenced cutting rates and markets predict it will cut another full percentage point[13] by this time next year.

Markets also expect the European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, and the Reserve Bank to cut rates significantly.

Read more:

Vital Signs. If we fall into a recession (and we might) we'll have ourselves to blame[14]

The Bank’s “house position[15]” on unemployment is that we can go down to 4.5% before worrying about triggering inflation (not that there’s much sign of that happening).

Another way to say that is that unemployment has to reverse course and get down to a barely-precedented 4.5% before there’s much hope of the Reserve Bank meeting the inflation target it is meant to be aiming for.

Perhaps the most important question facing the Australian economy is how aggressively the bank will act to attempt to get it there and to keep the economy afloat. Time will tell.

Read more:

RBA update: Governor Lowe points to even lower rates[16]

ABS 6202.0[6]

In part it is going up because more people not previously regarded as unemployed are looking for work (and not finding it).

It isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but it is also exactly what would be expected when wage growth was sluggish. Households are doing what they can to assemble more income.

The world economy is in trouble

Global economic conditions are concerning. This week Eurpoe’s second-biggest economy Germany[7] announced that its economy shrank by 0.1% in the second quarter of 2019, putting it on track to meet what some people call the technical definition of a recession.

Figures out of China regarding industrial production were also worrying, with factory output climbing more slowly than at any time in the last 17 years.

The US stock market climbed 1.5% on Tuesday after the Trump administration announced it would delay some of its new tariffs on China, but slid twice that amount the next day on the news from Germany and China.

Read more:

Are Trump's tariffs legal under the WTO? It seems not, and they are overturning 70 years of global leadership[8]

The fall in stocks led to a flight to the relative safety of government bonds. This caused the yield on 10 year US government bonds to fall below that of the 2 year bonds, a so-called “inverted yield curve” of the kind usually seen before a recession. The last time the US yield curve inverted was before the US Great Recession of 2008.

None of this is good for Australia. With roughly 20% of our economy powered by exports, we need the countries we export to to be doing well.

As Reserve Bank deputy governor Guy Debelle put it in a speech[9] on Thursday

Australia also has significant exports to China in both tourism and education. To date, these have been broadly unaffected by the slowdown in the Chinese economy. But a further significant slowing in the Chinese economy and household incomes would clearly pose a risk.

There’s no telling how low rates will go

There have been plenty of competing views[10] about the state of the Australian economy over the past few years.

Not long ago most economists who thought interest rates would move thought they would rise[11]. The Reserve Bank governor suggested the same.

But its increasingly clear that secular stagnation[12] is gripping advanced economies around the world. In response, the US Federal Reserve has recommenced cutting rates and markets predict it will cut another full percentage point[13] by this time next year.

Markets also expect the European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, and the Reserve Bank to cut rates significantly.

Read more:

Vital Signs. If we fall into a recession (and we might) we'll have ourselves to blame[14]

The Bank’s “house position[15]” on unemployment is that we can go down to 4.5% before worrying about triggering inflation (not that there’s much sign of that happening).

Another way to say that is that unemployment has to reverse course and get down to a barely-precedented 4.5% before there’s much hope of the Reserve Bank meeting the inflation target it is meant to be aiming for.

Perhaps the most important question facing the Australian economy is how aggressively the bank will act to attempt to get it there and to keep the economy afloat. Time will tell.

Read more:

RBA update: Governor Lowe points to even lower rates[16]

References

- ^ testimony (rba.gov.au)

- ^ old man time (youtu.be)

- ^ Wage Price Index (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ ABS 6345.0 (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ unemployment figures (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ ABS 6202.0 (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ Germany (www.destatis.de)

- ^ Are Trump's tariffs legal under the WTO? It seems not, and they are overturning 70 years of global leadership (theconversation.com)

- ^ speech (rba.gov.au)

- ^ competing views (theconversation.com)

- ^ thought they would rise (theconversation.com)

- ^ secular stagnation (www.afr.com)

- ^ another full percentage point (rba.gov.au)

- ^ Vital Signs. If we fall into a recession (and we might) we'll have ourselves to blame (theconversation.com)

- ^ house position (theconversation.com)

- ^ RBA update: Governor Lowe points to even lower rates (theconversation.com)

Authors: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW