Did someone say ‘election’?: how politics met pandemic to create ‘fortress Queensland’

- Written by Chris Salisbury

Government responses to COVID-19 in Australia have received, by and large, bipartisan support. An exception, it seems, is the imposition of restrictions on interstate movement. State borders have become a lightning rod for political friction and feverish commentary. With elections in the frame, this has escalated into apparent “border wars”.

Going hard on borders

The latest salvos follow alarming coronavirus outbreaks in Victoria and, in lesser numbers, Greater Sydney.

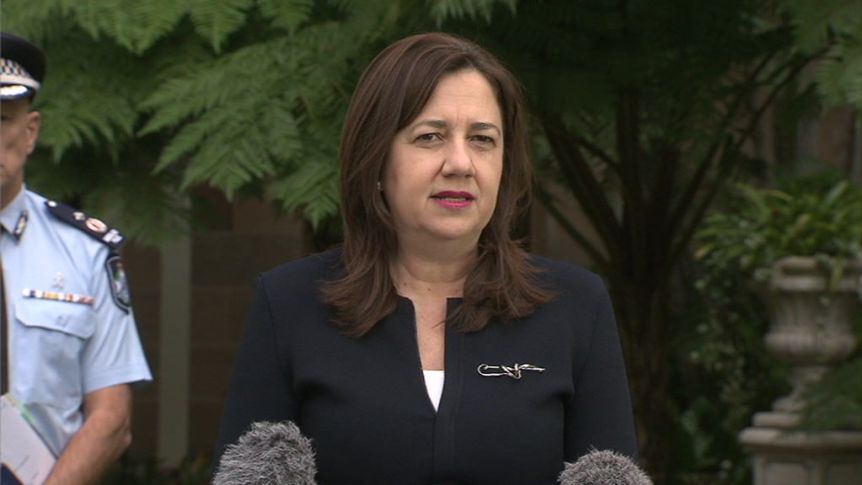

After partially reopening Queensland’s borders mere weeks ago, Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk surprised some by reimposing a “hard” border closure effective from the weekend. As case numbers ballooned in Melbourne and instances occurred of infected returning travellers “breaching” quarantine measures, many Queenslanders anticipated toughened restrictions – and indeed welcomed them.

Read more: Naming and shaming two young women shows the only 'enemies of the state' are the media

Get your politics analysis from academic experts, not vested interests.

It should be remembered that the Queensland government’s generally successful handling of the pandemic crisis, including its readiness to close borders, enjoys broad approval. Some wondered why this latest border closure extended to the ACT as well, where there are no active cases.

But a hard line on borders to effectively “put Queenslanders’ health first” is a popular move. Support for the closures even came from a possibly unexpected source in Gold Coast Mayor Tom Tate. Amid heightened anxiety, residents here will take comfort from the seeming security of “fortress Queensland”.

Election fever in the air

In Queensland, pandemic conditions currently favour the incumbent premier – in stark comparison to Daniel Andrews’s situation in Victoria. With community transmission largely under control, Palaszczuk has played a steady hand in easing lockdown restrictions, informed by her chief health officer’s advice.

While impacts on the state’s economy and unemployment levels remain worrying – and potentially politically damaging – everything is viewed through the prism of the government’s ability to manage the crisis. These circumstances seemingly lend themselves to taking an “abundance” of caution.

This has in turn invited criticism from some business quarters, but it’s an approach that suits both the times and the premier’s style.

A recent coronavirus outbreak in Brisbane’s south tested the premier’s leadership and her government’s responsiveness, providing a reminder of the disease’s unpredictability. Subsequently, taking a resolute stance on border measures, in defiance especially of naysayers from southern states and Canberra, will only boost Palaszczuk’s standing in her (often parochial) home state. With an election less than 12 weeks away, there are, variously, more rewards than risks in unapologetically prioritising the protection of Queenslanders’ health.

But as that election nears, both the premier and her LNP counterpart, Deb Frecklington, will look to turn circumstances more clearly to their political advantage. Opinion polls show the LNP holding a slim two-party-preferred lead – yet, perhaps significantly, Palaszczuk has a distinct lead as voters’ preferred premier.

The premier adopting a position of ‘strength’

Many in Queensland see Palaszczuk as personable and a “safe pair of hands”. This reassuring attribute might be well suited to these uncertain times.

With Palaszczuk’s leadership stocks running high, Queensland voters can anticipate a presidential-style election campaign come October. Messaging has already surfaced singling out Palaszczuk as a “strong premier”, suggesting she’s the leader to make “strong decisions”. But Labor may well tread this path warily, remembering what befell Campbell Newman, the last Queensland premier who campaigned relentlessly on “strong” characteristics.

Read more: Coalition maintains Newspoll lead federally and in Queensland; Biden's lead over Trump narrows

Admittedly, accentuating “strength” counters claims of being indecisive or too cautious, critiques that have dogged Palaszczuk’s leadership until now. This approach could work well politically, so long as events – or potentially the federal government – don’t turn against the premier’s handling of the pandemic. If there’s a heightened element to the crisis in coming weeks, the situation could reverse quickly for Palaszczuk’s government, leaving the premier wearing much of the blow-back.

Even Anna Bligh’s much-lauded leadership during the destructive 2010-11 cyclones and floods in Queensland didn’t translate to a long-term boost in support. But the looming state election is a more short-term prospect. The pandemic will remain front and centre, with Palaszczuk’s crisis management still very much in the spotlight.

When to oppose in opposition?

The spread of COVID-19 has presented a political challenge for the opposition in Queensland.

The LNP’s past criticism of the Palaszczuk government over the state’s border closure has come back to bite it. Echoing their leader, throughout June several LNP MPs (supported by the prime minister no less) called repeatedly for the border’s reopening. Events since, understandably, have forced an about-face from LNP figures. They’re now advocating “tougher” border measures at the risk of appearing inconsistent.

Regardless, the opposition finds itself – ironically – having to be cautious about the limits of striking a point of difference. This much is obvious in Frecklington’s newly struck tone of resigned consensus with the government’s border position. This is a bind opposition parties are experiencing nationwide, a hard reality especially in states and territories with elections nearing.

The LNP, having gambled on criticising the government’s border restrictions, now wears the fallout. Labor has pounced on the opportunity, in early signs of a de facto election campaign. Social media posts have highlighted how Frecklington – who’s had to endure her own party’s turmoil of late – called for Queensland’s borders to be opened “early” on dozens of occasions.

Queenslanders can expect to be reminded of this “rashness” from now until the election. The LNP, meanwhile, must identify issues not necessarily coronavirus-related – such as law and order or water security in regional Queensland – to provide it some campaign cut-through.

Palaszczuk in the driver’s seat

Notably, for ten of the past 13 years, a woman has been premier of Queensland. Whichever major party wins October’s election, a woman will be leader for (likely) a further four years. With Palaszczuk emphasising – in the face of LNP criticisms – that “the lady’s not for turning” from her border stance, she gives herself every chance to remain that leader.

This article first appeared in The Conversation. It is republished with permission