Westpac's panicked response to its money-laundering scandal looks ill-considered

- Written by Louis de Koker, Professor of Law, La Trobe University

Westpac’s board has jettisoned its chief executive, Brian Hartzer[1], just hours after he reportedly told his team mainstream Australia was not overly concerned about the bank’s 23 million alleged breaches[2] of anti-money-laundering laws, including handling transactions potentially involving child sex abuse.

Westpac's announcement to the Australian Securities Exchange.[3]

Harzter will receive a year’s salary in lieu of notice, worth A$2.68 million. Had he stayed on, he would have been eligible for share rights worth $20 million.

Westpac’s chairman, Lindsay Maxted, will bring forward his own retirement to the first half of 2020.

But far more customers have already been thrown overboard.

The emergency response[4] Westpac rushed out a few days ago abandoned thousands throughout the Pacific and other regions.

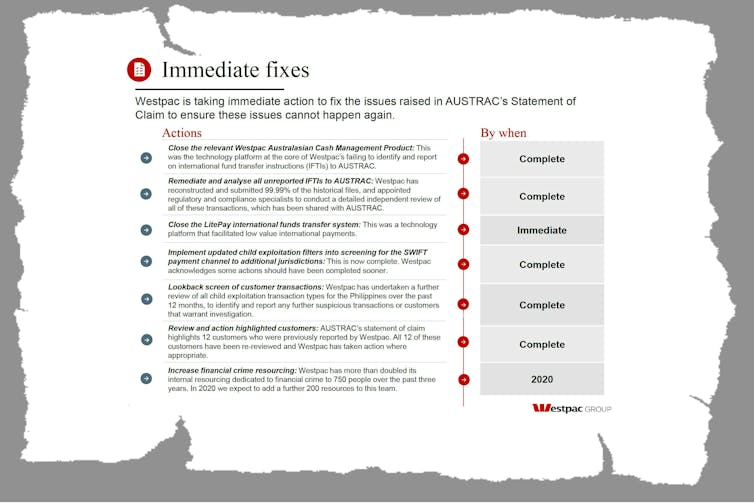

Westpac announced its “immediate fixes” included immediately shutting down “LitePay”, its low-cost system for customers to transfer money from one country to another.

Westpac's announcement to the Australian Securities Exchange.[3]

Harzter will receive a year’s salary in lieu of notice, worth A$2.68 million. Had he stayed on, he would have been eligible for share rights worth $20 million.

Westpac’s chairman, Lindsay Maxted, will bring forward his own retirement to the first half of 2020.

But far more customers have already been thrown overboard.

The emergency response[4] Westpac rushed out a few days ago abandoned thousands throughout the Pacific and other regions.

Westpac announced its “immediate fixes” included immediately shutting down “LitePay”, its low-cost system for customers to transfer money from one country to another.

Extract from Westpac's weekend response.[5]

Customers used LitePay to send “remittances” to family members outside Australia.

The bank’s response statement implicitly acknowledged the importance of these remittances. It noted LitePay was launched as part of a broader initiative with Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs “to improve the livelihoods of men and women in the Pacific”.

Shutting down LitePay, without providing customers viable alternatives, is likely to do the opposite.

Westpac has abandoned customers who need it

The United Nations recognises[6] remittances as vital in helping millions out of poverty. It estimates about one in nine people around the world rely on remittances from family members working abroad.

Remittances are particularly important throughout the Pacific, from the Philippines to a small island nation like Tonga, where the money adults working abroad send home accounts[7] for more than 40% of their GDP.

Read more:

If Australia cares about Pacific nations, we should also invest in their care givers[8]

Extract from Westpac's weekend response.[5]

Customers used LitePay to send “remittances” to family members outside Australia.

The bank’s response statement implicitly acknowledged the importance of these remittances. It noted LitePay was launched as part of a broader initiative with Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs “to improve the livelihoods of men and women in the Pacific”.

Shutting down LitePay, without providing customers viable alternatives, is likely to do the opposite.

Westpac has abandoned customers who need it

The United Nations recognises[6] remittances as vital in helping millions out of poverty. It estimates about one in nine people around the world rely on remittances from family members working abroad.

Remittances are particularly important throughout the Pacific, from the Philippines to a small island nation like Tonga, where the money adults working abroad send home accounts[7] for more than 40% of their GDP.

Read more:

If Australia cares about Pacific nations, we should also invest in their care givers[8]

A Western Union branch facade in Cebu City, Philippines.

Shuttersock

Remittances can be sent via companies like Western Union and Moneygram, but these are relatively expensive and generally focused on urban customers. In Australia members of expatriate communities with connections to their home countries established lower-cost remittance services. These small businesses facilitated the transfer of small amounts – generally[9] less than A$500 a month – at an affordable price. They did so using accounts with banks like Westpac.

From 2011, remitters were required to register with the anti-money-laundering agency, AUSTRAC, and comply with anti-money-laundering laws. Compliance obligations include identifying customers and verifying their identities, generally known as “know your customer” or “KYC” measures.

Then, in 2013, Australian banks joined a global trend to “de-bank” small remitters, due to money-laundering and terrorist-financing risks. Over the next few years the accounts of more than 700 small Australian remitters[10], many of which were AUSTRAC-registered, were closed.

Compliance obligations

Westpac was the last of Australia’s big four banks to withdraw from servicing remitters. In November 2014 then chief executive Gail Kelly said[11]:

The regulatory requirements for anti-money laundering are you need to know your customer and, in the case of remitters, you need to know your customer’s customers. That’s quite a responsibility. You do millions of these transactions and if one goes wrong and is connected with terrorism financing, that’s a real problem.

The need to “know your customer’s customers” was not, however, a clear regulatory obligation. In 2015 the global standard-setter for controls on money laundering and terrorist financing, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF),

stated[12] it did not require this.

The task force had also stated since 2014 that risks relating to remittances should be assessed on a case-by-case basis[13]. The low risk of criminals or terrorism financiers sending money through remittance providers from Australia to Pacific island countries has since been confirmed by a 2017 report[14] by AUSTRAC and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Read more:

With increased anti-money laundering measures, banks are shutting out women[15]

Whatever the potential risk small remitters pose, the fact of de-banking created real risks. As research by myself and Supriya Singh[16] into the effect on African communities found:

Some worry that if the money stops their parents will starve. Young people will join terrorist groups or decide to flee hunger by joining the boats. One Eritrean community leader said his cousin fled to the Mediterranean shores and died in the attempt to reach Europe.

De-banking remitter accounts lessened the compliance obligations of Westpac and others. But it had the ironic effect of reducing the transparency of remittance flows for law enforcement. In many cases payments continued to flow using unregulated channels and even cash[17], giving rise to crime risks to users and to Australia.

Leaving customers high and dry

It is a further irony that having de-banked small remittances services due to compliance concerns, Westpac ran afoul of anti-money-laundering obligations with LitePay, which it launched in 2016[18].

AUSTRAC’s charges against Westpac outline 12 cases involving repeated suspicious payments to the Philippines using LitePay. The money transfers matched known child-exploitation transaction patterns. Westpac failed to identify and report these prior to 2018 because it lacked appropriate detection measures for those transaction patterns.

But AUSTRAC says Westpac fixed the problems with LitePay in June 2018. Instead, AUSTRAC alleges, it is in its non-LitePay channels where the bank has still not implemented such measures. It is therefore in those channels that it continued to fail “to identify activity indicative of child exploitation risks[19]”.

So why shut down LitePay? Why leave high and dry all its honest customers and the families who depend on remittances?

Read more:

How states rocked by conflict could harness funds from their diasporas[20]

Westpac has options. It could improve its control measures further. It could launch a collaborative[21], risk-based program aimed at re-banking small registered community-based remitters, starting with those servicing low-risk regions in the Pacific.

These remitters know their communities and users well. Together with Westpac’s improved systems, they could deliver an even safer system.

Jettisoning LitePay looks like a classic case of throwing out the baby with the bathwater – and doing so with scant regard for Westpac’s corporate social responsibilities.

A Western Union branch facade in Cebu City, Philippines.

Shuttersock

Remittances can be sent via companies like Western Union and Moneygram, but these are relatively expensive and generally focused on urban customers. In Australia members of expatriate communities with connections to their home countries established lower-cost remittance services. These small businesses facilitated the transfer of small amounts – generally[9] less than A$500 a month – at an affordable price. They did so using accounts with banks like Westpac.

From 2011, remitters were required to register with the anti-money-laundering agency, AUSTRAC, and comply with anti-money-laundering laws. Compliance obligations include identifying customers and verifying their identities, generally known as “know your customer” or “KYC” measures.

Then, in 2013, Australian banks joined a global trend to “de-bank” small remitters, due to money-laundering and terrorist-financing risks. Over the next few years the accounts of more than 700 small Australian remitters[10], many of which were AUSTRAC-registered, were closed.

Compliance obligations

Westpac was the last of Australia’s big four banks to withdraw from servicing remitters. In November 2014 then chief executive Gail Kelly said[11]:

The regulatory requirements for anti-money laundering are you need to know your customer and, in the case of remitters, you need to know your customer’s customers. That’s quite a responsibility. You do millions of these transactions and if one goes wrong and is connected with terrorism financing, that’s a real problem.

The need to “know your customer’s customers” was not, however, a clear regulatory obligation. In 2015 the global standard-setter for controls on money laundering and terrorist financing, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF),

stated[12] it did not require this.

The task force had also stated since 2014 that risks relating to remittances should be assessed on a case-by-case basis[13]. The low risk of criminals or terrorism financiers sending money through remittance providers from Australia to Pacific island countries has since been confirmed by a 2017 report[14] by AUSTRAC and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Read more:

With increased anti-money laundering measures, banks are shutting out women[15]

Whatever the potential risk small remitters pose, the fact of de-banking created real risks. As research by myself and Supriya Singh[16] into the effect on African communities found:

Some worry that if the money stops their parents will starve. Young people will join terrorist groups or decide to flee hunger by joining the boats. One Eritrean community leader said his cousin fled to the Mediterranean shores and died in the attempt to reach Europe.

De-banking remitter accounts lessened the compliance obligations of Westpac and others. But it had the ironic effect of reducing the transparency of remittance flows for law enforcement. In many cases payments continued to flow using unregulated channels and even cash[17], giving rise to crime risks to users and to Australia.

Leaving customers high and dry

It is a further irony that having de-banked small remittances services due to compliance concerns, Westpac ran afoul of anti-money-laundering obligations with LitePay, which it launched in 2016[18].

AUSTRAC’s charges against Westpac outline 12 cases involving repeated suspicious payments to the Philippines using LitePay. The money transfers matched known child-exploitation transaction patterns. Westpac failed to identify and report these prior to 2018 because it lacked appropriate detection measures for those transaction patterns.

But AUSTRAC says Westpac fixed the problems with LitePay in June 2018. Instead, AUSTRAC alleges, it is in its non-LitePay channels where the bank has still not implemented such measures. It is therefore in those channels that it continued to fail “to identify activity indicative of child exploitation risks[19]”.

So why shut down LitePay? Why leave high and dry all its honest customers and the families who depend on remittances?

Read more:

How states rocked by conflict could harness funds from their diasporas[20]

Westpac has options. It could improve its control measures further. It could launch a collaborative[21], risk-based program aimed at re-banking small registered community-based remitters, starting with those servicing low-risk regions in the Pacific.

These remitters know their communities and users well. Together with Westpac’s improved systems, they could deliver an even safer system.

Jettisoning LitePay looks like a classic case of throwing out the baby with the bathwater – and doing so with scant regard for Westpac’s corporate social responsibilities.

References

- ^ jettisoned its chief executive, Brian Hartzer (www.asx.com.au)

- ^ 23 million alleged breaches (www.austrac.gov.au)

- ^ Westpac's announcement to the Australian Securities Exchange. (www.asx.com.au)

- ^ emergency response (www.westpac.com.au)

- ^ Extract from Westpac's weekend response. (cdn.theconversation.com)

- ^ recognises (www.un.org)

- ^ accounts (data.worldbank.org)

- ^ If Australia cares about Pacific nations, we should also invest in their care givers (theconversation.com)

- ^ generally (www.un.org)

- ^ 700 small Australian remitters (www.austlii.edu.au)

- ^ Gail Kelly said (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ stated (www.fatf-gafi.org)

- ^ case-by-case basis (www.fatf-gafi.org)

- ^ a 2017 report (www.austrac.gov.au)

- ^ With increased anti-money laundering measures, banks are shutting out women (theconversation.com)

- ^ research by myself and Supriya Singh (theconversation.com)

- ^ unregulated channels and even cash (classic.austlii.edu.au)

- ^ launched in 2016 (www.reuters.com)

- ^ to identify activity indicative of child exploitation risks (www.austrac.gov.au)

- ^ How states rocked by conflict could harness funds from their diasporas (theconversation.com)

- ^ collaborative (classic.austlii.edu.au)

Authors: Louis de Koker, Professor of Law, La Trobe University