They've cut deeming rates, but what are they?

- Written by Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has cut deeming rate for large investments from 3.25% to 3%, and for smaller ones from 1.75% all the way down to 1%, backdated to the start of July[1].

But exactly is a deeming rate, and why does it matter so much to about one million Australians on benefits, among them around about 630,000 age pensioners?

It’s a topic I covered in The Conversation mid last week in an explainer[2] that went all the way back to the beginning, or at least the most recent beginning, when treasurer Paul Keating brought deeming rates back to Australia’s benefits system in 1991.

Read more: Deeming rates explained. What is deeming, how does it cut pensions, and why do we have it?[3]

Before that, applicants for the pension were able to pass income tests by ensuring that their assets didn’t earn much income, a service banks and other institutions were happy to provide for them.

From 1991, on applicants for the age pension (and later other benefits) were “deemed” to have earned from their financial assets amounts set by the government, whatever they actually earned.

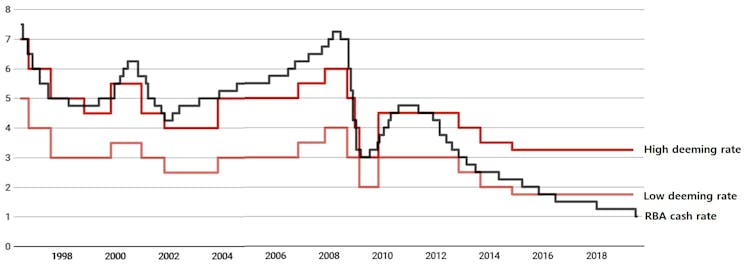

For most of the past two decades both the high deeming rate (which at the moment applies to financial assets in excess of A$51,800 for singles and $86,200 for couples) and also the low deeming rate (for lesser assets) have been below the Reserve Bank’s cash rate, benefiting applicants who could earn more than those low rates while continuing to get benefits.

Deeming rates versus RBA cash rate, July 1996 - July 2019, per cent

Australian government, RBA[4]

Then, beginning with prime minister Kevin Rudd (who, to be fair to him, in 2009 delivered the biggest ever increase in the pension[5] – $100 a fortnight for singles and $76 for couples) and continuing under his successors Gillard, Abbott, Turnbull and Morrision, the government adjusted the deeming rate more slowly, meaning that as the Reserve Bank’s cash rate fell, both the high and low deeming rates ended up above it.

Australian government, RBA[4]

Then, beginning with prime minister Kevin Rudd (who, to be fair to him, in 2009 delivered the biggest ever increase in the pension[5] – $100 a fortnight for singles and $76 for couples) and continuing under his successors Gillard, Abbott, Turnbull and Morrision, the government adjusted the deeming rate more slowly, meaning that as the Reserve Bank’s cash rate fell, both the high and low deeming rates ended up above it.

The new deeming rates: 3% and 1%

The decisions announced by Frydenberg on Sunday go a long way to putting things right.

The lower deeming rate will once more be close to the cash rate (exactly at the cash rate, for as long as the cash rate stays at 1%). The higher deeming rate will not be, but then it probably shouldn’t be.

The higher rate applies to the return on financial assets (including shares) worth more than $51,800. As Frydenberg pointed out on Sunday, many of those assets return much more, not much less, than the deeming rate:

It could apply to superannuation returns, and that’s averaging around 5.5%. Or to yields on ASX 200 stocks, which are averaging about 4.5%

The low deeming rate is on the face of it unfair, because few bank deposits pay 1%. The special retirees accounts offered by ANZ and the Commonwealth pay 0.25%. Many deposit accounts pay nothing.

But the low rate applies to financial assets all the way up to $51,800 ($86,200 for couples), and to all types of assets. Many pension applicants are likely to earn a total return on those assets well above 1%.

Deeming is by design, rough and ready. There will always be complaints, and of late those complaints had force. They are now back broadly where they should be.

Read more:

Deeming rates explained. What is deeming, how does it cut pensions, and why do we have it?[6]

The new deeming rates: 3% and 1%

The decisions announced by Frydenberg on Sunday go a long way to putting things right.

The lower deeming rate will once more be close to the cash rate (exactly at the cash rate, for as long as the cash rate stays at 1%). The higher deeming rate will not be, but then it probably shouldn’t be.

The higher rate applies to the return on financial assets (including shares) worth more than $51,800. As Frydenberg pointed out on Sunday, many of those assets return much more, not much less, than the deeming rate:

It could apply to superannuation returns, and that’s averaging around 5.5%. Or to yields on ASX 200 stocks, which are averaging about 4.5%

The low deeming rate is on the face of it unfair, because few bank deposits pay 1%. The special retirees accounts offered by ANZ and the Commonwealth pay 0.25%. Many deposit accounts pay nothing.

But the low rate applies to financial assets all the way up to $51,800 ($86,200 for couples), and to all types of assets. Many pension applicants are likely to earn a total return on those assets well above 1%.

Deeming is by design, rough and ready. There will always be complaints, and of late those complaints had force. They are now back broadly where they should be.

Read more:

Deeming rates explained. What is deeming, how does it cut pensions, and why do we have it?[6]

References

- ^ backdated to the start of July (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ explainer (theconversation.com)

- ^ Deeming rates explained. What is deeming, how does it cut pensions, and why do we have it? (theconversation.com)

- ^ Australian government, RBA (guides.dss.gov.au)

- ^ biggest ever increase in the pension (www.sbs.com.au)

- ^ Deeming rates explained. What is deeming, how does it cut pensions, and why do we have it? (theconversation.com)

Authors: Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

Read more http://theconversation.com/theyve-cut-deeming-rates-but-what-are-they-120333