The behavioural economics of discounting, and why Kogan would profit from discount deception

- Written by Ralph-Christopher Bayer, Professor of Economics , University of Adelaide

Kogan Australia has grown from a garage to an online retail giant in a little more than a decade. Key to its success have been its discount prices.

But apparently not all of those discounts have been legit, according to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.

The consumer watchdog has accused[1] the home electronics and appliances retailer of misleading customers, by touting discounts on more than 600 items whose prices it had sneakily raised by at least the same percentage.

Kogan is yet to have its day in court[2], so we won’t dwell on its case specifically.

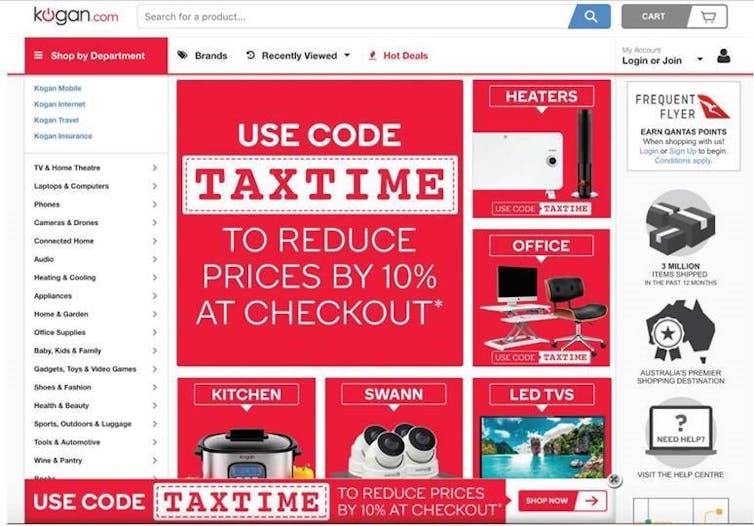

The ACCC alleges Kogan’s ‘TAXTIME’ promotion offered a 10% discount on items whose prices had all been raised by the equivalent percentage.

ACCC[3]

The ACCC alleges Kogan’s ‘TAXTIME’ promotion offered a 10% discount on items whose prices had all been raised by the equivalent percentage.

ACCC[3]

But the scenario does raise an interesting question. How effective are these types of price manipulation? After all, checking and comparing prices is dead easy online. So what could a retailer possibly gain?

Well, as it happens, potentially quite a lot.

Because consumers are human beings, our actions aren’t necessarily rational. We have strong emotional reactions to price signals. The sheer ubiquity of discounts demonstrate they must work.

Lets review a couple of findings from behavioural (and traditional) economics that help explain why discounting – both real and fake – is such an effective marketing ploy.

Save! Save! Save!

In standard economics, consumers are assumed to base their purchasing decisions on absolute prices. They make “rational” decisions, and the “framing” of the price does not matter.

Psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky[4] challenged this assumption with their insights into consumer behaviour. Their best-known contribution to behavioural economics is “prospect theory[5]” – a psychologically more realistic alternative to the classical theory of rational choice.

Kahneman and Tversky argued that behaviour is based on changes, which were relative. Framing a price as involving a discount therefore influences our perception of its value.

The prospect of buying something leads us to compare two different changes: the positive change in perceived value from taking ownership of a good (the gain); and the negative change experienced from handing over money (the loss). We buy if we perceive the gain to outweigh the loss.

Suppose you are looking to buy a toaster. You see one for $99. Another is $110, with a 10% discount – making it $99. Which one would you choose?

Evaluating the first toaster’s value to you is reasonably straightforward. You will consider the item’s attributes against other toasters and how much you like toast versus some other benefit you might attain for $99.

Standard economics says your emotional response involves weighing the loss of $99 against the gain of owning the toaster.

For the second toaster you might do all the same calculations about features and value for money. But behavioural economics tells us the discount will provoke a more complex emotional reaction than the first toaster.

Research shows most of us will tend to “segregate” the price from the discount; we will feel separately the emotion from the loss of spending $99 and the gain of “saving” $11.

Economist Richard Thaler demonstrated this in a study involving 87 undergraduate students[6] at Cornell University. He quizzed them on a series of scenarios like the following:

Mr A’s car was damaged in a parking lot. He had to spend $200 to repair the damage. The same day the car was damaged, he won $25 in the office football pool. Mr B’s car was damaged in a parking lot. He had to spend $175 to repair the damage. Who was more upset?

Just five students said both would be equally upset, while 67 (more than 72%) said Mr B. Similar hypotheticals elicited equally emphatic results.

Economists now refer to this as the “silver lining effect[7]” – segregating a small gain from a larger loss results in greater psychological value than integrating the gain into a smaller loss.

The result is we feel better handing over money for a discounted item than the same amount for a non-discounted item.

Annual ‘Black Friday’ sales, associated with frenzied shopping behaviour, have spread from the United States to other parts of the world. Here shoppers scramble for discounted television sets in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in November 2018.

Sebastiao Moreira/EPA

Annual ‘Black Friday’ sales, associated with frenzied shopping behaviour, have spread from the United States to other parts of the world. Here shoppers scramble for discounted television sets in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in November 2018.

Sebastiao Moreira/EPA

Must end soon!

Another behavioural trick associated with discounts is creating a sense of urgency, by emphasising the discount period will end soon.

Again, the fact people typically evaluate prospects as changes from a reference point comes into play.

The seller’s strategy is to shift our reference points so we compare the current price with a higher price in the future. This makes not buying feel like a future loss. Since most humans are loss-averse, we may be nudged to avoid that loss by buying before the discount expires.

Expiry warnings also work through a second behavioural channel: anticipated regret.

Some of us are greatly influenced to behave according to whether we think we will regret it in the future.

Economic psychologist Marcel Zeelenberg and colleagues demonstrated this in experiments with students at the University of Amsterdam. Their conclusion: regret-aversion better explains choices[8] than risk-aversion, because anticipation of regret can promote both risk-averse and risk-seeking choices.

Depending to what extent we have this trait, an expiry warning can compel us to buy now, in case we need that item in the future and will regret not having taken the opportunity to buy it when discounted.

Discounting is thus an effective strategy to get us to buy products we actually don’t need.

Look no further!

But what about the fact that it is so easy to compare prices online? Why doesn’t this fact nullify the two effects we’ve just discussed?

Here the standard economics of consumer search would agree that consumers might be misled despite being perfectly rational.

If a consumer judges a discount promotion is genuine, they have a tendency to assume it is less likely they will find a lower price elsewhere. This belief makes them less likely to continue searching.

In experiments on this topic[9], my colleague Changxia Ke and I have found a discernible “discount bias”. The effect is not necessarily large, depending on circumstances, but even a small nudge towards choosing a retailer with discounted items over another could end up being worth millions.

Read more: Why consumers fall for 'sales', but companies may be using them too much[10]

Once a consumer has made a decision and bought an item, they are even less likely to search for prices. They therefore may never learn a discount was fake.

There are entire industries where it is general practice to frame prices this way. Paradoxically, because this makes consumers search less for better deals, it allows all sellers to charge higher prices.

The bottom line: beware the emotional appeal of the discount. Whether real or fake, the human tendency is to overrate them.

References

- ^ consumer watchdog has accused (www.accc.gov.au)

- ^ have its day in court (www.accc.gov.au)

- ^ ACCC (www.accc.gov.au)

- ^ Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (www.newyorker.com)

- ^ prospect theory (www.its.caltech.edu)

- ^ a study involving 87 undergraduate students (bear.warrington.ufl.edu)

- ^ silver lining effect (pdfs.semanticscholar.org)

- ^ regret-aversion better explains choices (pure.uva.nl)

- ^ experiments on this topic (eprints.qut.edu.au)

- ^ Why consumers fall for 'sales', but companies may be using them too much (theconversation.com)

Authors: Ralph-Christopher Bayer, Professor of Economics , University of Adelaide