Those future tax cut promises... they're nowhere near as big as you'd think

- Written by Matthew Gray, Director, ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods, Australian National University

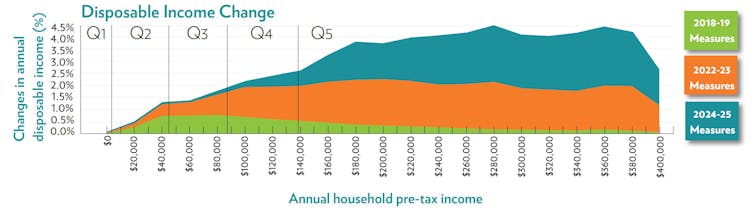

The 2018 budget contained big tax measures – worth A$143 billion over the next decade[1] – initially targeted at lower and middle income Australians, but after five or so years to be heavily weighted towards higher income Australians. The 2019 Budget doubled down, including an extra $158 billion of measures[2], again heavily weighted towards higher income earners.

It’s possible to draw graphs showing that if the tax cuts came to pass, higher earners would be enormously better off[3] compared to everyone else, but the graphs miss a really important point.

National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling[4]

The point is that high end tax rates would have been wound back over time anyway to stop people moving into higher tax brackets as their income grew.

The graph below shows the average personal income tax rate paid by households since 2000 and projections of what they will be through to 2029 under four assumptions – the (unlikely) scenario of no tax change; the 2018-19 Budget change; the combined 2018-19 and 2029-20 Budget changes; and the same combined scenario but with lower than average wage growth (2.5% per year).

Household average tax rates, 2000 to 2029

National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling[4]

The point is that high end tax rates would have been wound back over time anyway to stop people moving into higher tax brackets as their income grew.

The graph below shows the average personal income tax rate paid by households since 2000 and projections of what they will be through to 2029 under four assumptions – the (unlikely) scenario of no tax change; the 2018-19 Budget change; the combined 2018-19 and 2029-20 Budget changes; and the same combined scenario but with lower than average wage growth (2.5% per year).

Household average tax rates, 2000 to 2029

Takes account of tax changes in 2018 and 2019 budgets and one-off energy supplement.

ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods[5]

This tells a very interesting story. The average household tax rate reached a peak of 15.5% in 2002 and then declined to 11.7% in 2010. Since then it has climbed to reach 13.7% in 2017.

Our modelling finds that without the tax changes announced in the 2018 and 2019 budgets wage growth and bracket creep would push the average rate to a record high of 16.4% in 2029.

It is unlikely that either side of politics would let this happen. The effects of bracket creep would almost certainly be at least partly eliminated through adjustments to tax thresholds or rates much earlier.

Read more:

NATSEM: federal budget will widen gap between rich and poor[6]

Our analysis shows shows that the 2018 budget tax cuts[7] would have reduced but not entirely eliminated the effects of bracket creep.

The tax cuts announced in the 2019 budget[8] go further and mean that the average tax rate in 2024 would be much the same as in 2017, but that it would then start to grow again to be quite a bit higher at 14.5% by 2029 (assuming the wage increases projected in the Budget are correct).

While no one knows what wage growth will be over the next decade, the experience of the past decade suggests it could be substantially lower than the budget projection of 3.5% per year.

If it was 2.5% the average tax rate would be lower in 2024 than today and remain lower through to 2029.

Of course, projecting wages growth out that far is crystal ball territory and it is impossible to have much idea.

The biggest beneficiaries of the tax cuts are certainly households in the upper half of the income distribution. But this doesn’t mean their tax cuts weren’t necessary.

Welfare payments are largely “set-and-forget”. The rates increase over time with either prices or earnings. But tax rates need to be adjusted over time in order to stop more and more people being pushed into higher tax brackets.

Analysis of tax changes that ignores this will exaggerate their effects.

Read more:

What just happened to our tax? Here's an explanation you'll understand[9]

Takes account of tax changes in 2018 and 2019 budgets and one-off energy supplement.

ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods[5]

This tells a very interesting story. The average household tax rate reached a peak of 15.5% in 2002 and then declined to 11.7% in 2010. Since then it has climbed to reach 13.7% in 2017.

Our modelling finds that without the tax changes announced in the 2018 and 2019 budgets wage growth and bracket creep would push the average rate to a record high of 16.4% in 2029.

It is unlikely that either side of politics would let this happen. The effects of bracket creep would almost certainly be at least partly eliminated through adjustments to tax thresholds or rates much earlier.

Read more:

NATSEM: federal budget will widen gap between rich and poor[6]

Our analysis shows shows that the 2018 budget tax cuts[7] would have reduced but not entirely eliminated the effects of bracket creep.

The tax cuts announced in the 2019 budget[8] go further and mean that the average tax rate in 2024 would be much the same as in 2017, but that it would then start to grow again to be quite a bit higher at 14.5% by 2029 (assuming the wage increases projected in the Budget are correct).

While no one knows what wage growth will be over the next decade, the experience of the past decade suggests it could be substantially lower than the budget projection of 3.5% per year.

If it was 2.5% the average tax rate would be lower in 2024 than today and remain lower through to 2029.

Of course, projecting wages growth out that far is crystal ball territory and it is impossible to have much idea.

The biggest beneficiaries of the tax cuts are certainly households in the upper half of the income distribution. But this doesn’t mean their tax cuts weren’t necessary.

Welfare payments are largely “set-and-forget”. The rates increase over time with either prices or earnings. But tax rates need to be adjusted over time in order to stop more and more people being pushed into higher tax brackets.

Analysis of tax changes that ignores this will exaggerate their effects.

Read more:

What just happened to our tax? Here's an explanation you'll understand[9]

References

- ^ A$143 billion over the next decade (budget.gov.au)

- ^ extra $158 billion of measures (budget.gov.au)

- ^ enormously better off (theconversation.com)

- ^ National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling (www.ausbudget.org)

- ^ ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods (csrm.cass.anu.edu.au)

- ^ NATSEM: federal budget will widen gap between rich and poor (theconversation.com)

- ^ 2018 budget tax cuts (csrm.cass.anu.edu.au)

- ^ 2019 budget (budget.gov.au)

- ^ What just happened to our tax? Here's an explanation you'll understand (theconversation.com)

Authors: Matthew Gray, Director, ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods, Australian National University