NSW deputy premier threatens to sue FriendlyJordies, reminding us that parody hits in a way traditional media can't

- Written by Laura Glitsos, Lecturer in Arts and Humanities, Edith Cowan University

New South Wales Deputy Premier John Barilaro is reportedly threatening legal action[1] against YouTuber and political satirist Jordan Shanks, better known as friendlyjordies, over allegedly defamatory and “racist” comments. Shanks’s parodying of Barilaro has included imitating him with a strong Italian accent.

In 2019, Shanks received a similar legal threat[2] from then-politician Clive Palmer after labelling him a “dense humpty dumpty”, among other profanities. Shanks’s video responding[3] to Palmer’s lawsuit has been viewed more than one million times, with a likes-to-dislikes ratio indicating overwhelming support from viewers.

The latest threat against Shanks reminds us of the key role parody and satirisation now play in the nation’s political discourse. This type of humour provides a way to discuss issues in a way traditional media outlets can’t risk doing. Perhaps this is because parody, by its very nature, is expected to be cheeky (and even offensive).

Add to this contemporary Western society’s desire for freedom of speech[4] — coupled with our increasing connectedness afforded by the internet — and one could argue it has never been easier to create and consume political satire.

But where does the value of this content lie? And is there evidence to suggest it can influence people’s personal politics?

Necessary provocation?

Effective political satire will often cause outrage[5]. Anger may be directed at the satirist or the issue being discussed; in either case, a strong emotional response indicates the audience is tuned in.

Take Shanks, who has been criticised repeatedly for his offensive[6] brand of comedy. And despite being quite open about his political allegiance to the Labor Party[7], he has offended people right across the political spectrum[8].

But regardless of anyone’s personal views on him, one could argue Shanks’s brashness and crudity, combined with scathing wit, are what make him relatable to Australians. As former Curtin University academic Rebecca Higgie[9] explains in her research, Australians’ unique sense of larrikinism[10] popularises this particular brand of political discourse.

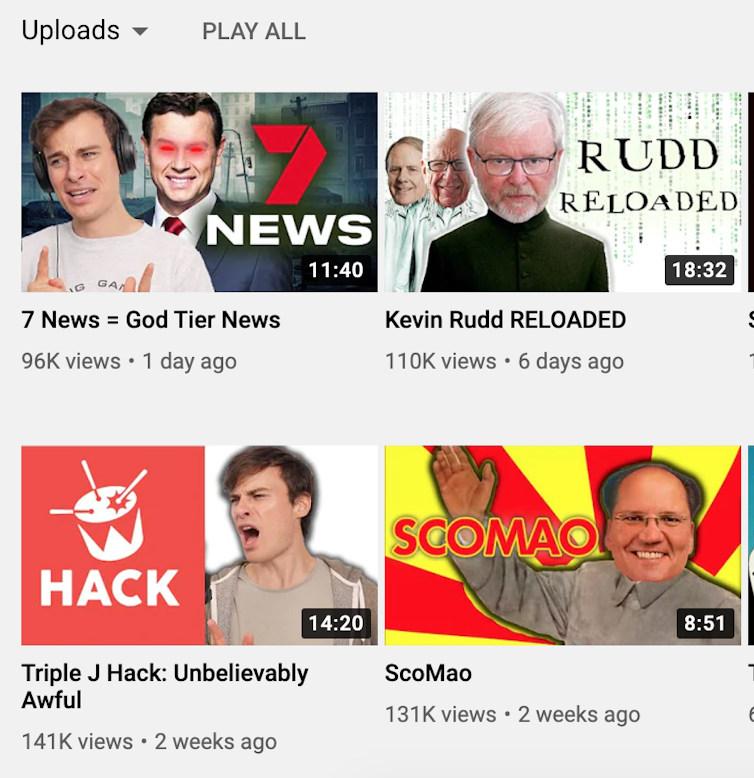

Shanks joined YouTube in 2013 and his videos have since amassed more than 127 million views.

Screenshot/Youtube

Shanks joined YouTube in 2013 and his videos have since amassed more than 127 million views.

Screenshot/Youtube

Prior to[11] the pandemic, a major study[12] of the 2019 federal election found trust in government was at its lowest since the 1970s. In such a landscape, where there is widespread concern regarding how democracy is performing, it becomes easier to understand why some people may trust satirists over politicians and/or mainstream media.

The former, at least, are more willing to put their brand on the line and embrace vitriol from the public.

At last count, Shanks had more than 480,000 subscribers on YouTube. As a crude comparison, the Australian government’s official channel had just over 600[13], while SBS Australia[14] had about 42,000. (The ABC[15] and SkyNews both had many more.)

Sick of old formats

Research[16] published in March confirmed that “user-generated parodies”, such as those made by Shanks, are far better received by audiences than parodies produced through mainstream or commercial media outlets.

This is in keeping with the general trend towards the fracturing of legacy media institutions, as well as increasing calls for media diversity — manifested in ex-Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s bid for a royal commission[17] into News Corp’s ideological domination of Australia’s media landscape.

Myriad studies and surveys carried out in a marketing context have also found user-generated content, as opposed to “professional” or “traditional” content, is more likely to resonate[18], be trusted[19], be remembered[20] and influence[21] consumers.

This is particularly illuminating in light of the federal government’s recent problematic “consent” videos[22], attempting to teach sexual consent by using tacos and milkshakes as metaphors for sex. The videos were heavily criticised by the media and public.

How social media changed the game

According to research[23], the explosion of social media has unsurprisingly generated an increase in political parodies. And these have certainly become difficult to ignore for anyone engaged in Australia’s broader political conversation.

Apart from friendlyjordies, major satirists leading on this front include the fake news publication The Betoota Advocate[24], satirical comedy group The Chaser[25] and YouTube channel The Juice Media[26], which gave us “Honest Government Ads”.

That said, there’s still contention as to whether political parodies can “change people’s minds” on political issues. One 2006 study[27] found the political comedy of The Daily Show With Jon Stewart led to audiences having a more negative view of the politicians being parodied, as well as a more cynical view of the overall US electoral system.

Similarly, researchers[28] from Paris’s Sorbonne Business School claim funny YouTube videos had a real stake in negatively impacting Donald Trump’s “Build a Wall” policy.

The YouTube video[29] “Do You Wanna Build a Wall? Donald Trump (Frozen Parody)” received more than 37 million views and 467,000 interactions, while a similar Peppa Pig-themed parody was viewed more than 49 million times.

Then again, there is research that suggests otherwise. In one study[30] focusing on US television presenter Stephen Colbert’s brand of political satire, researchers analysed how the show was received by both liberal and conservative audiences. They found

[…] there was no significant difference between the groups in thinking Colbert was funny, but conservatives were more likely to report that Colbert only pretends to be joking.

This suggests while viewers from all ends of the political spectrum can “enjoy” Colbert’s political satire, conservatives didn’t necessarily receive the satirical jokes as satire. That is, they didn’t always sense Colbert was being sarcastic.

The researchers suggest this may be because of Colbert’s deadpan delivery style, which could leave ambiguity for some viewers. According to them, conservative viewers found a way to make Colbert’s liberal humour agreeable to their own ideology. They liked the show, but not for the same reason as liberal viewers.

Healthy democracy

Sometimes parody can help all of us see the lighter side of things. For example, the Twitter account “Aus Gov Just Googled[31]” probably gives most people a laugh, except maybe members of the actual government. A recent tweet mocking the government’s misguided sexual consent videos could be enjoyed by both ends of the political spectrum:

It remains to be seen how Barilaro’s legal threats against Shanks will play out. But Australia has a legacy of political satire that connects to our sense of larrikinism and our egalitarian brand of “taking the piss”. Shanks is an example of how, in the age of the internet, anyone can extend and champion this legacy.

And while some online parodies might be absolute shockers — especially if you’re on the receiving end — they remain a sign of a healthy democracy.

References

- ^ threatening legal action (www.youtube.com)

- ^ similar legal threat (www.bbc.com)

- ^ responding (www.youtube.com)

- ^ freedom of speech (humanrights.gov.au)

- ^ cause outrage (ijoc.org)

- ^ offensive (law.anu.edu.au)

- ^ allegiance to the Labor Party (www.youtube.com)

- ^ right across the political spectrum (au.rollingstone.com)

- ^ Rebecca Higgie (static1.squarespace.com)

- ^ larrikinism (www.britannica.com)

- ^ Prior to (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ a major study (www.anu.edu.au)

- ^ 600 (www.youtube.com)

- ^ SBS Australia (www.youtube.com)

- ^ ABC (www.youtube.com)

- ^ Research (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ bid for a royal commission (www.aph.gov.au)

- ^ resonate (info.photoslurp.com)

- ^ be trusted (www.business2community.com)

- ^ be remembered (www8.gsb.columbia.edu)

- ^ influence (www8.gsb.columbia.edu)

- ^ problematic “consent” videos (theconversation.com)

- ^ According to research (www.annualreviews.org)

- ^ The Betoota Advocate (www.betootaadvocate.com)

- ^ The Chaser (chaser.com.au)

- ^ The Juice Media (www.youtube.com)

- ^ One 2006 study (journals.sagepub.com)

- ^ researchers (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ YouTube video (www.youtube.com)

- ^ one study (journals.sagepub.com)

- ^ Aus Gov Just Googled (twitter.com)