“Providing an opportunity for people to apply for a visa that will probably never come seems both cruel and unnecessary”.

This was the view of an expert panel, commissioned by Home Affairs Minister Clare O'Neil, on Australia’s dysfunctional parent migration system. Parents wanting to migrate to Australia to join their children face extreme delays, even if they can afford a contributory visa, which costs almost $50,000 per person.

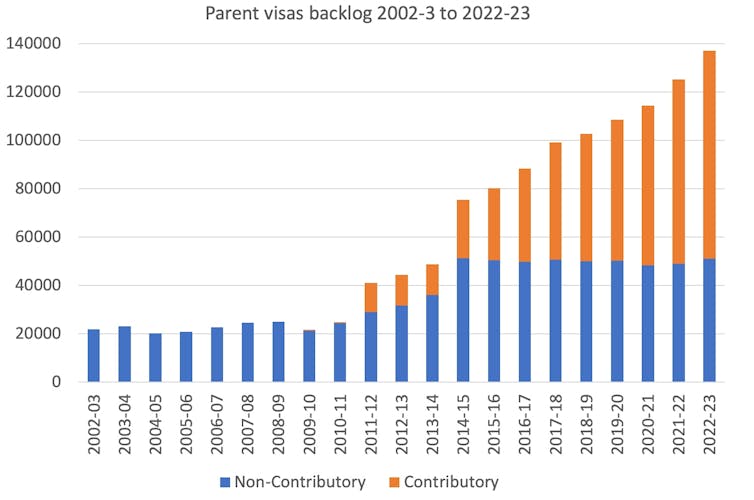

My report for the Scanlon Foundation Research Institute, published today, finds the backlog of applications for permanent parent visas is approaching 140,000 and has tripled in a decade. Wait times for a contributory visa are at least 12 years, or at least 30 years for a cheaper visa.

How can we fix this? Whichever way the government turns, it faces unpalatable policy choices with unwanted electoral consequences.

The parent visa conundrum

The parent visa pipeline includes 86,000 applications for so-called “contributory” visas, and 51,000 for “non-contributory” visas.

These are first- and second-class migration options, with price tags to match.

The $47,955 per person charge for a contributory visa is justified on the basis that these first-class parents “contribute” to the cost of the public services they will access as they age. But the Productivity Commission argues the revenue raised is “a fraction of the fiscal costs” that parents will impose, especially by drawing on health services.

The charge is better understood as a premium paid in return for “quicker” processing. Initially, this worked. When the Howard government first introduced contributory visas in 2003, well-off families were able to swiftly settle parents in Australia, usually within two years. But program numbers were capped from the start, and demand rapidly outstripped supply.