Australia's anti-lockdown tribe battles on against the evidence

- Written by Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

You might have thought the “lockdown wars” in Australia were over.

After all, Australia navigated the pandemic better than essentially any other country in 2020.

We closed our international border in March, used an early and relative light lockdown in NSW to get contact testing and tracing up and running, squelched costly hotel quarantine leaks in Victoria with more dramatic measures, and generally kept Australia as COVID-free as possible.

We adopted the wise principle, borne out by so much tragic international experience, that we could not have a functioning economy with a pandemic raging.

The overwhelming focus of public policy has now shifted to getting people vaccinated. But some of the anti-lockdown tribe are battling on, suggesting our border controls and lockdown didn’t save lives.

Are they right? No.

Their latest argument uses a US National Bureau of Economic Research working paper[1] by academics from the University of Southern California and the RAND Corporation that looks at “excess deaths”. That is, it compares total deaths from all causes in a particular jurisdiction with an estimate of “expected” deaths in that jurisdiction based on historical data.

Their data covers all 50 US states and 43 nations, including Australia. Their conclusion is that “shelter-in-place” policies were associated with an increase in excess mortality, with the exception of three countries: Australia, Malta and New Zealand.

So this isn’t a good argument against our approach. Nor did the authors find any statistical significant result covering more than the immediate weeks following shelter-in-place implementation in the more internally comparable US data.

Nonetheless it’s worth examining this paper, and also looking at what Australian data on excess deaths is showing.

Read more: Yes, lockdowns are costly. But the alternatives are worse[2]

A brave empirical method

The National Bureau of Economic Research is a distinguished organisation. It has published nine of my working papers[3]. But this does not bestow some kind of magical status on them. It doesn’t mean they are peer-reviewed. Rather, it is an automatic privilege accompanying bureau affiliation.

Thus every paper comes with the disclaimer that “working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes” and “have not been peer-reviewed”.

The paper latched on to by the anti-lockdown tribe uses an empirical method known as an “event study”. Such studies were popularised in financial economics thanks to an influential 1969 paper[4] on stock prices by American economist Gene Fama and colleagues.

Eugene Fama 1969 paper ‘The Adjustment of Stock Prices to New Information’. CC BY-SA[5]

Eugene Fama 1969 paper ‘The Adjustment of Stock Prices to New Information’. CC BY-SA[5]

Fama has been called “father of modern finance[6]” for his work on the “efficient markets hypothesis” – the idea that asset prices reflect all available information, so it is impossible in the long run to “beat” the market.

The efficient markets hypothesis is a big and important idea in financial economics. It rightly led to the 2013 Nobel prize for economics, which Fama shared with University of Chicago colleague Lars Peter Hansen and Yale University’s Robert Shiller, who built on Fama’s work and concluded that markets are often very far from efficient.

Whatever one’s view about the rationality of asset prices, it is important to understand the “event study” method relies crucially on rationality in financial markets and the efficiency of securities prices. As one survey article of event studies[7] notes:

The usefulness of such a study comes from the fact that, given rationality in the marketplace, the effects of an event will be reflected immediately in security prices. Thus a measure of the event’s economic impact can be constructed using security prices observed over a relatively short time period.

Using an event study to assess a noisy measure of mortality in decidedly inefficient political markets (if one can even call them that in this case) is a million miles away from the purpose and internal logic of event studies in securities markets.

The nice way to describe using an event study to assess pandemic policy is that it’s “brave”.

Bridge Street in central Sydney, June 29 2021. Mick Tsikas/AAP

Bridge Street in central Sydney, June 29 2021. Mick Tsikas/AAP

Australian data on deaths

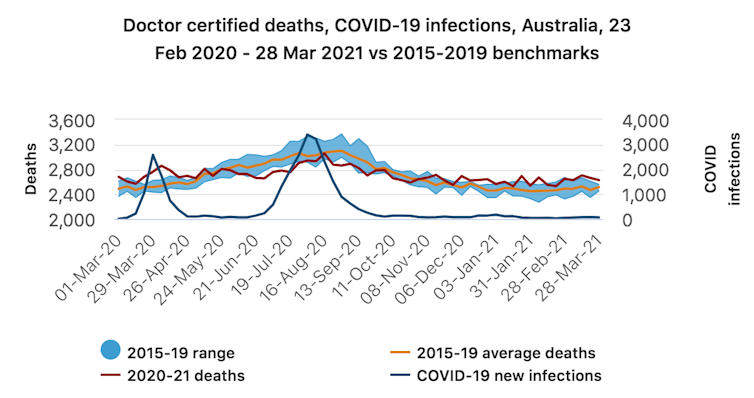

The Australian Bureau of Statistic collates definitive statistics about deaths after reports from state coroners are finalised. It usually publishes these annually, in September.

Due to the interest in deaths due to the pandemic, however, the bureau has been publishing monthly “provisional mortality statistics” based on doctor-certified deaths. (About 80-85% of all deaths are certified by doctors, without a coroner determining the cause.)

The provisional statistics[8] show Australia had slightly fewer non-COVID-related deaths in 2020 than normally the case (an average of 385.6 deaths per day, compared to the baseline average of 385.8.)

ABS, CC BY-SA[9] In 2020 and so far in 2021[10] Australians have been less likely than normal to die of heart disease and strokes, and dramatically less likely to die from flu. Read more: You can't fix the economy if you can't see it: how the ABS became our secret weapon[11] What about suicides? A common claim by the anti-lockdown tribe is that suicides have risen due to people being socially isolated and losing work. But early evidence from insurance companies[12] on suicides shows the opposite. There’s a good reason for this. As Simon Swanson, the chief executive of ClearView Life Assurance, told the House Standing Committee[13] on Economics on June 25: If you read our annual report last year you would have seen we increased assumptions for suicide. That did not actually happen — suicide actually went down —and in our research part of that was because people were participating in a global pandemic and everyone was in this together. The second impact was there was an incredible increase in telehealth, which was an interesting part of technology actually delivering to consumers. Everyone was in this together. There may, of course, be other mental health impacts from lockdowns. But there are no perfect options. We will have a greater array of policy options when at least 80% of the population are vaccinated. With apologies to John Keating (played by Robin Williams) in Dead Poets Society: “‘Twas always thus, and always thus will be.”

ABS, CC BY-SA[9] In 2020 and so far in 2021[10] Australians have been less likely than normal to die of heart disease and strokes, and dramatically less likely to die from flu. Read more: You can't fix the economy if you can't see it: how the ABS became our secret weapon[11] What about suicides? A common claim by the anti-lockdown tribe is that suicides have risen due to people being socially isolated and losing work. But early evidence from insurance companies[12] on suicides shows the opposite. There’s a good reason for this. As Simon Swanson, the chief executive of ClearView Life Assurance, told the House Standing Committee[13] on Economics on June 25: If you read our annual report last year you would have seen we increased assumptions for suicide. That did not actually happen — suicide actually went down —and in our research part of that was because people were participating in a global pandemic and everyone was in this together. The second impact was there was an incredible increase in telehealth, which was an interesting part of technology actually delivering to consumers. Everyone was in this together. There may, of course, be other mental health impacts from lockdowns. But there are no perfect options. We will have a greater array of policy options when at least 80% of the population are vaccinated. With apologies to John Keating (played by Robin Williams) in Dead Poets Society: “‘Twas always thus, and always thus will be.” References

- ^ working paper (www.nber.org)

- ^ Yes, lockdowns are costly. But the alternatives are worse (theconversation.com)

- ^ nine of my working papers (www.nber.org)

- ^ an influential 1969 paper (www.jstor.org)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ father of modern finance (www.chicagobooth.edu)

- ^ survey article of event studies (www.jstor.org)

- ^ The provisional statistics (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ so far in 2021 (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ You can't fix the economy if you can't see it: how the ABS became our secret weapon (theconversation.com)

- ^ evidence from insurance companies (thewest.com.au)

- ^ told the House Standing Committee (parlinfo.aph.gov.au)

Authors: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW