NFTs hit the big league, but not everyone will win from this new sports craze

- Written by Adam Karg, Associate Professor, Business School, Swinburne University of Technology

Some buy sporting memorabilia for love. Others for money.

The world record for most money paid for a sports-related item goes to the original Olympic manifesto written in 1892 by International Olympic Committee founder Pierre de Coubertin. It changed hands in 2019 for US$8.8 million[1]. In second place is the New York Yankees jersey worn by legendary American baseball player Babe Ruth, sold in 2012 for USA$4.4 million[2].

As in all markets for collectibles, scarcity equals value.

Which is why sport organisations, memorabilia sellers and collectors are getting excited about non-fungible tokens – or NFTs – a blockchain-enabled technology that proves unique ownership of digital content.

NFTs open up a huge new market to sell limited-edition images, videos and artwork. They also enable the original licensees – be it sports organisations or individual athletes – to share in resale profits.

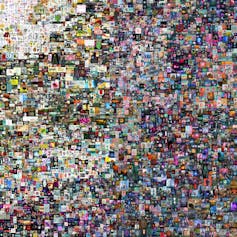

Beeple’s collage ‘Everydays: The First 5000 Days’ sold at Christie’s for US$69 million. Christie's/AP

Beeple’s collage ‘Everydays: The First 5000 Days’ sold at Christie’s for US$69 million. Christie's/AP

NFTs are already sweeping the art market. In March, auction house Christie’s sold an NFT of a work by American digital artist Mike Winkelmann[3], known as Beeple, for US$69 million. Auction house Sotheby’s last month sold a single pixel[4] for $US1.36 million.

Could we see similar NFT values in the sports collectibles market? Quite possibly.

Though tangible items such as uniforms, balls and bats will likely continue to be prized collectibles, collectors are already paying big bucks for digital versions of old favourites such as trading cards.

Leading the game is the US National Basketball Association, which began selling limited-edition “Top Shots” – digitally packaged and NFT-authenticated video highlight clips – in October 2020[5]. Like traditional trading cards, these are sold in “packs”. Some videos are common, others rare. One such rare “moment” – in reality about half a moment – of basketball superstar LeBron James dunking reportedly changed hands in April for US$387,000[6].

Who knows what someone might pay for that moment in decades to come?

It might be millions more. Or much much less. Because this market, for all its early promises of rich rewards, is not without its downsides, with potential for significant environmental and social costs.

What are non-fungible tokens (NFTs)?

Something is fungible when it has a standardised and interchangeable value. It is replaceable by something else just like it. Cash is the obvious example. Non-fungible essentially means something unique, non-replaceable.

So NFTs[7] are essentially digital certificates, secured with blockchain technology, that authenticate an item’s provenance – that it is a limited edition or one of kind – and enable it to be bought and sold as such.

An NFT provides scarcity of digital content that can be relatively easily copied – a photo of Indian cricket great Sachin Tendulkar making a world-record score, for example, or a video of tennis No. 1 Ash Barty winning at Wimbledon.

Sports trading cards for sale in a department store in California. TonelsonProductions/Shutterstock

Sports trading cards for sale in a department store in California. TonelsonProductions/Shutterstock

Read more: What are NFTs and why are people paying millions for them?[8]

There are big opportunities

The potential riches are evident from the NBA’s Top Shot[9] sales, which accounted for US$500 million in transactions[10] in the first three months of the year. This was a third of the total US$1.5 billion in NFT transactions, according to DappRadar[11], which tracks blockchain markets.

Last month San Francisco-based NBA team the Golden State Warriors was the first US professional sports team to issue its own NFT collection, which includes limited-edition digital versions of championship rings and ticket stubs[12].

Individual athletes are also selling their own branded items in NFT form. NFL quarterback Patrick Mahomes, for example, is selling signed digital artwork[13]. Champion skateboarder Mariah Duran and paralympian Scout Bassett are among a group of elite women athletes who will release NFTs this month[14]. Expect to see many more selling NFTs in the wake of the Toyko Olympics.

There are also risks

But there are some big downsides.

The first is environmental – because of the energy used in blockchain verification processes.

Of course, making and transporting physical goods has a range of environmental impacts, but by one calculation the carbon footprint of selling an NFT artwork is almost 100 times that[15] of selling and transporting a print version. In February, French digital artist Joanie Lemercier cancelled the sale of six works, and urged others to do the same[16], after calculating those sales would use the same amount of electricity in ten seconds as his studio used in two years.

Eliminating this downside of NFTs will depend on more efficient technology and more renewable energy.

Read more: NFTs: why digital art has such a massive carbon footprint[17]

The second is social – of people only seeing NFTs as a way to make money.

As in any market where prices are rising rapidly, there is the danger of a speculative bubble. Here, the risk is that buyers spend big on virtual items that may end up being virtually worthless when the bubble bursts.

Last year also saw large and continuing market growth in traditional sport collectibles such as trading cards[18], along with retail investment in cryptocurrencies and stock markets more generally. So, while the value attached to NFTs may prove to be enduring, it is possible some part of the early interest in sport NFTs is driven by “irrational exuberance” and patterns of people spending more time and money online due to the COVID pandemic.

Read more: NFTs are much bigger than an art fad – here's how they could change the world[19]

There are likely to be many more sport organisations and athletes peddling their digital wares in the near future. It is though, difficult to predict whether sales will continue this trajectory, how and when this trend might “normalise”, or if NFTs indeed represent a speculative bubble.

Particularly for fans playing in this market, care should be taken to not let emotions trump prudence and good judgment.

References

- ^ in 2019 for US$8.8 million (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ in 2012 for USA$4.4 million (www.espn.com)

- ^ Mike Winkelmann (www.beeple-crap.com)

- ^ a single pixel (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ in October 2020 (www.foxsports.com.au)

- ^ for US$387,000 (www.si.com)

- ^ NFTs (theconversation.com)

- ^ What are NFTs and why are people paying millions for them? (theconversation.com)

- ^ Top Shot (www.si.com)

- ^ US$500 million in transactions (www.forbes.com)

- ^ according to DappRadar (dappradar.com)

- ^ championship rings and ticket stubs (www.espn.com.au)

- ^ signed digital artwork (www.espn.com.au)

- ^ release NFTs this month (www.sportico.com)

- ^ 100 times that (qz.com)

- ^ urged others to do the same (twitter.com)

- ^ NFTs: why digital art has such a massive carbon footprint (theconversation.com)

- ^ such as trading cards (www.forbes.com)

- ^ NFTs are much bigger than an art fad – here's how they could change the world (theconversation.com)

Authors: Adam Karg, Associate Professor, Business School, Swinburne University of Technology