Are too many corporate mergers harming consumers? We won't know if we don't check

- Written by Caron Beaton-Wells, Professor, Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne

Compared with the grand cause of climate change or the pointed self-interest of income tax, competition policy is a decidedly unsexy election issue. So it’s hardly surprising that no party is running hot on the issue – not even the Labor Party, although it has put some notable reforms[1] on the election slate.

But competition policy matters to all of us.

It’s what stands between being able to pick and choose goods and services with a range of prices and quality on the one hand, and on the other being dictated to by one or a handful of sellers charging as much and offering as little possible.

Keeping markets competitive necessitates a debate about economics, law and regulation. It may be technical but we pay dearly if we don’t have it.

Existing policies to protect competition in Australia are not in bad shape. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) is regarded as one of the world’s best[2] competition regulators. But there is always more that can be done.

Most of all, the commission needs more empirical evidence to know if it is doing enough to prevent competitive markets being distorted by a few dominant companies.

Highly concentrated

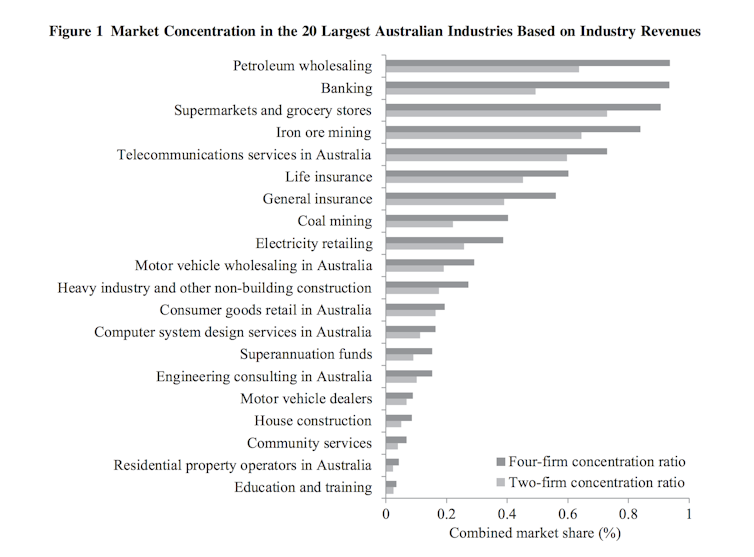

Many Australian markets are concentrated[3] – dominated by a few big players. Think of banks, energy retailers, telecommunications, supermarkets and petrol sellers.

Market concentration in the 20 largest Australian industries based on industry revenues, calculated by Andrew Leigh and Adam Triggs using IBISWorld data in 2016.

The Australian Economic Review, FAL[4][5]

Market concentration in the 20 largest Australian industries based on industry revenues, calculated by Andrew Leigh and Adam Triggs using IBISWorld data in 2016.

The Australian Economic Review, FAL[4][5]

Each year the ACCC considers hundreds of mergers or acquisitions that add to concentration.

The competition watchdog has the power to begin formal proceedings to block a merger if it is judged to give the merged entity too much market power. In reality, however, the regulator opposes very few acquisitions.

In 2017-18[6], for example, the ACCC examined 281 mergers. It “pre-assessed” 252 as not requiring a review. Of the 29 reviewed, 17 (61%) were cleared unconditionally. This means just 4% of all examined mergers were opposed. The previous year it was also just 4%[7].

Whether Australia’s high concentration levels are due to lax merger control standards is open for debate. So too is whether concentration necessarily harms competition.

The Grattan Institute has pointed the finger at other factors[8]: too much regulation in some sectors, creating barriers to entry (such as zoning laws for grocery retailers), and too little regulation in others (such as access conditions for ports).

It is generally accepted that a higher degree of industrial consolidation may be justified to enable efficiencies of scale in an economy that is relatively small and geographically dispersed. Enhanced efficiency should mean lower prices for consumers.

At least, that’s what the economic theory tells us. But is that what has been happening in practice?

Merger retrospectives

In other countries, economists and policy makers have the benefit of empirical studies that measure what effect mergers or acquisitions have had on prices and other aspects of market performance. The studies look at merger deals not blocked by competition authorities. They examine whether acquisitions live up to the claims made by the merging parties at the time of the deal.

These “merger retrospectives” have shown that mergers, in reducing the number of competitors, do indeed raise prices. A comprehensive review of merger retrospectives [9] in the US found prices rose by 4.3% in nearly 95% of cases where mergers led to six or fewer significant competitors in a market. This finding is not unique to the US. A 2016 study in Europe[10] had similar results.

Retrospective analyses are regularly done by agencies overseas, including in Canada and Britain. But not in Australia.

Doing so would tell us if the ACCC’s system for making merger assessments is working. Depending on their scope, merger retrospectives might also provide valuable data for other important policy debates, such as whether concentration levels suppress investment, innovation and wage growth, or increase inequality[11].

Labor proposals

In 2013 the Abbott government initiated a major independent review[12] of Australia’s competition policy framework and laws. Known as the Harper review, it was completed in 2015. Several significant amendments were made as a result. The most prominent was introducing an “effects test” – to determine if unilateral conduct has the purpose or likely effect of substantially lessening competition.

Read more: Explainer: what is the competition 'effects test'?[13]

Now federal Labor is supporting further reforms, including retrospective analysis[14] of mergers.

These reviews may be complex and expensive, but Labor is also proposing an increase in the ACCC budget.

It is also proposing higher fines for companies breaking competition laws. This is based on Australia being an outlier on the international stage[15] in terms of the relatively low fines[16] it imposes to punish and deter breaches of competition laws.

The proposal is to increase the maximum penalty for a breach of consumer and competition laws from A$10 million to A$50 million, or 30% of the annual sales of the product or service relating to the breach, multiplied by the duration of the infringement. This emulates the European approach to calculating fines. It would mean the starting point for the fine imposed in the notorious Visy price-fixing case would have been more than A$200 million[17], instead of A$36 million.

Read more: Cartels caught ripping off Australian consumers should be hit with bigger fines[18]

The ACCC supports increasing corporate fines[19], so this proposal should be taken seriously.

But reforms should not just be concerned with anti-competitive conduct after it happens. That won’t undo the damage to businesses, workers and consumers.

What matters as much, if not more, is having a legal framework to ensure markets do not become overly concentrated, affording undue power to just a handful of firms, in the first place.

References

- ^ some notable reforms (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ one of the world’s best (www.accc.gov.au)

- ^ are concentrated (adamtriggs.files.wordpress.com)

- ^ The Australian Economic Review (adamtriggs.files.wordpress.com)

- ^ FAL (artlibre.org)

- ^ 2017-18 (www.accc.gov.au)

- ^ it was also just 4% (www.accc.gov.au)

- ^ pointed the finger at other factors (grattan.edu.au)

- ^ comprehensive review of merger retrospectives (mitpress.mit.edu)

- ^ 2016 study in Europe (publications.europa.eu)

- ^ increase inequality (www.oecd.org)

- ^ major independent review (competitionpolicyreview.gov.au)

- ^ Explainer: what is the competition 'effects test'? (theconversation.com)

- ^ retrospective analysis (www.andrewleigh.com)

- ^ outlier on the international stage (www.oecd.org)

- ^ relatively low fines (pursuit.unimelb.edu.au)

- ^ A$200 million (theconversation.com)

- ^ Cartels caught ripping off Australian consumers should be hit with bigger fines (theconversation.com)

- ^ increasing corporate fines (www.accc.gov.au)

Authors: Caron Beaton-Wells, Professor, Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne