To fix Australia's housing affordability crisis, negative gearing must go

- Written by Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

House prices are back in the news, and out of control.

In the past three months the median house price in Sydney has risen by more than A$100,000 to A$1.12 million. Sydney’s median residential property price (including houses and apartments) is now 2.6% above its previous high-water mark[1], recorded in August 2017, before lending criteria were tightened (and COVID-19 struck).

Even areas far from central Sydney, such as the Central Coast, have recorded double-digit percentage increases.

What exactly is driving these sharp rises is a matter of debate. Australia’s economic recovery from COVID-19 has been stronger than many thought. The prospect of most Australians being vaccinated and international borders reopening provides further hope – even if our vaccine roll-out has been less than stellar in its planning and execution.

Of course, interest rates are at historic lows. More to the point, loans that can be fixed for three or five years have become much cheaper and more widely used as well. This has given borrowers the capacity to borrow larger sums.

The federal government has contributed, too, with a suite of measures targeted at first-home buyers. Like all such measures, these look attractive at the individual level but simply translate into higher prices. Schemes like the “first home owner grant” should really be called the “seller subsidy”.

Finally there is the elephant in the room: irrational exuberance.

Who knows how much “fear of missing out” has played into price rises. Against the backdrop of a worldwide public health and economic crisis, one might think buyers would be a little more circumspect about their future incomes.

But apparently not so much.

Our housing affordability problem

Sadly, there is little new about the fact that Australia – and the largest capital cities in particular – have a serious housing affordability problem. It has been that way for at least a decade.

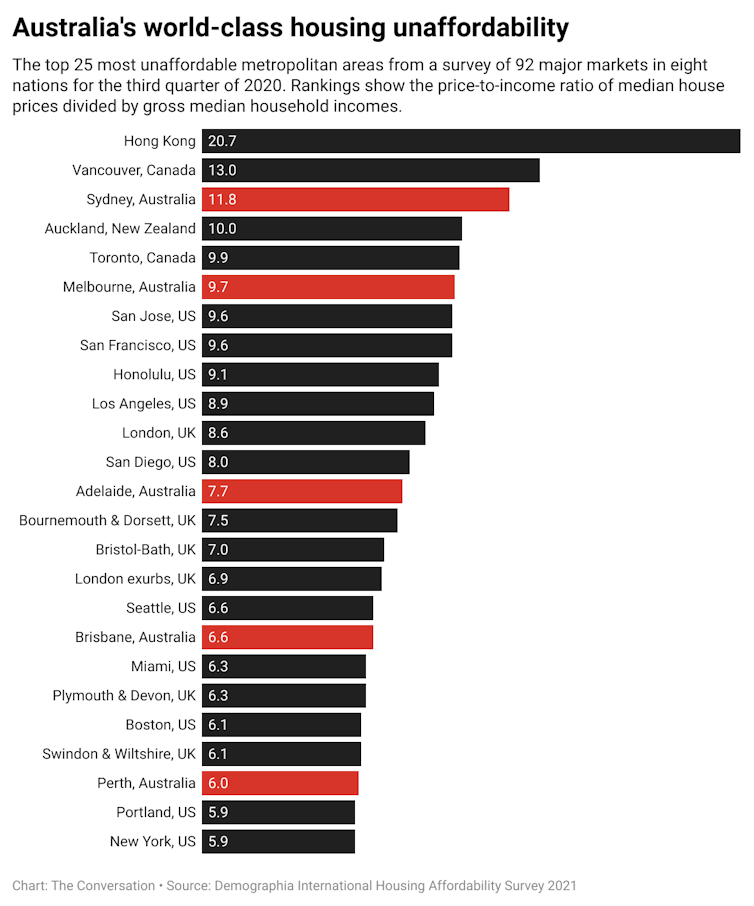

Sydney and Melbourne are routinely ranked among the top half-dozen most expensive cities in the world when comparing housing prices to average incomes earned in those cities.

Home ownership rates have fallen more or less constantly. Young people are basically excluded from home ownership unless they have very high incomes or parents with the means and inclination to provide financial help.

CC BY-SA[2] On top of this, household debt levels in Australia are disturbingly high – reflecting the large mortgages people who do manage to claw their way into the housing market have to take out. Sure, that is matched against the high asset values of the property they have bought. But as any student on economic history knows, that’s little comfort when an asset price bubble bursts. To put it another way: asset prices come and go, but debt is forever. So here we are again. The housing market is so frothy it has seriously reduced financial mobility at the individual level, and it threatens financial stability at the macro level. Read more: Zoning isn’t to blame for Australia’s soaring house prices[3] Quick fixes that won’t work Let’s start by ruling out some of the supposed quick fixes for getting property prices under control. Some say the Reserve Bank of Australia should hike interest rates to make it harder for borrowers to pay such high prices. But the RBA should mainly focus on its inflation target (one it has missed year after year), getting unemployment down and wages growth up. Those things all require low interest rates. To calm the frenzy, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority could use so-called “macroprudential tools”. These are requirements on financial institutions to limit systemic risks. In the past the financial regulator has set policies to limit credit growth and curb the proportion of “interest-only mortgages” (mortgages that don’t require principal payments). It can and should do these things, though it has a pretty spotty track record at acting in a timely and effective manner. Perhaps most importantly, both sides of politics need to revisit Australia’s almost unique and certainly odd system of allowing interest payments on rental properties to be offset against a person’s taxable income – that is, “negative gearing”. Read more: Negative gearing reforms could save A$1.7 billion without hurting poorer investors[4] Phasing out negative gearing Such deductions are permissible for other asset classes such as stocks – and have been for 100 years or so. But no “ordinary” Australian wage earner can get big loans to bet on the stock market. Even wealthy investors cannot get anything like the leverage they can in residential property in other asset classes. This is a peculiarity flowing from the amount of capital banks need to hold against property loans. It’s a market failure that should be addressed. The best way to do this – as I pointed out in a report for the McKell Institute[5] in mid-2015 – is to gradually phase out negative gearing over time, and allow it only for new dwellings in future. Expanding housing supply would also be very helpful. Labor took a policy based on this report to two elections. It lost both – although perhaps the last loss had more to with other things, including a quite separate and less appealing franking credit policy. Read more: Words that matter. What’s a franking credit? What’s dividend imputation? And what's 'retiree tax'?[6] The Coalition almost pre-empted Labor by reforming negative gearing in 2015/16. But then prime minister Malcolm Turnbull bowed to pressure from then treasurer and negative-gearing fan Scott Morrison. Housing affordability remains a serious problem in Australia. We need to tackle it now, and with a multi-pronged approach. If we don’t, we risk the future of young Australians and our financial system at the same time.

CC BY-SA[2] On top of this, household debt levels in Australia are disturbingly high – reflecting the large mortgages people who do manage to claw their way into the housing market have to take out. Sure, that is matched against the high asset values of the property they have bought. But as any student on economic history knows, that’s little comfort when an asset price bubble bursts. To put it another way: asset prices come and go, but debt is forever. So here we are again. The housing market is so frothy it has seriously reduced financial mobility at the individual level, and it threatens financial stability at the macro level. Read more: Zoning isn’t to blame for Australia’s soaring house prices[3] Quick fixes that won’t work Let’s start by ruling out some of the supposed quick fixes for getting property prices under control. Some say the Reserve Bank of Australia should hike interest rates to make it harder for borrowers to pay such high prices. But the RBA should mainly focus on its inflation target (one it has missed year after year), getting unemployment down and wages growth up. Those things all require low interest rates. To calm the frenzy, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority could use so-called “macroprudential tools”. These are requirements on financial institutions to limit systemic risks. In the past the financial regulator has set policies to limit credit growth and curb the proportion of “interest-only mortgages” (mortgages that don’t require principal payments). It can and should do these things, though it has a pretty spotty track record at acting in a timely and effective manner. Perhaps most importantly, both sides of politics need to revisit Australia’s almost unique and certainly odd system of allowing interest payments on rental properties to be offset against a person’s taxable income – that is, “negative gearing”. Read more: Negative gearing reforms could save A$1.7 billion without hurting poorer investors[4] Phasing out negative gearing Such deductions are permissible for other asset classes such as stocks – and have been for 100 years or so. But no “ordinary” Australian wage earner can get big loans to bet on the stock market. Even wealthy investors cannot get anything like the leverage they can in residential property in other asset classes. This is a peculiarity flowing from the amount of capital banks need to hold against property loans. It’s a market failure that should be addressed. The best way to do this – as I pointed out in a report for the McKell Institute[5] in mid-2015 – is to gradually phase out negative gearing over time, and allow it only for new dwellings in future. Expanding housing supply would also be very helpful. Labor took a policy based on this report to two elections. It lost both – although perhaps the last loss had more to with other things, including a quite separate and less appealing franking credit policy. Read more: Words that matter. What’s a franking credit? What’s dividend imputation? And what's 'retiree tax'?[6] The Coalition almost pre-empted Labor by reforming negative gearing in 2015/16. But then prime minister Malcolm Turnbull bowed to pressure from then treasurer and negative-gearing fan Scott Morrison. Housing affordability remains a serious problem in Australia. We need to tackle it now, and with a multi-pronged approach. If we don’t, we risk the future of young Australians and our financial system at the same time. References

- ^ 2.6% above its previous high-water mark (www.nation.lk)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Zoning isn’t to blame for Australia’s soaring house prices (theconversation.com)

- ^ Negative gearing reforms could save A$1.7 billion without hurting poorer investors (theconversation.com)

- ^ a report for the McKell Institute (research.economics.unsw.edu.au)

- ^ Words that matter. What’s a franking credit? What’s dividend imputation? And what's 'retiree tax'? (theconversation.com)

Authors: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW