The budget sets us up for an unreasonably slow recovery. Here's how

- Written by Brendan Coates, Program Director, Household Finances, Grattan Institute

Josh Frydenberg has told us his 2020 Budget is “all about jobs[1]”.

What he hasn’t said is that it is actually aiming for a slower recovery from the recession, as far as unemployment goes, than from most recessions in Australia’s history.

That’s both the budget’s explicit forecast and the result of the measures in it.

You would be forgiven for expecting the recovery from this recession to be faster than the recoveries from previous recessions. Previous recessions haven’t involved the government requiring businesses close their doors.

In most recessions the government isn’t able to switch things back on.

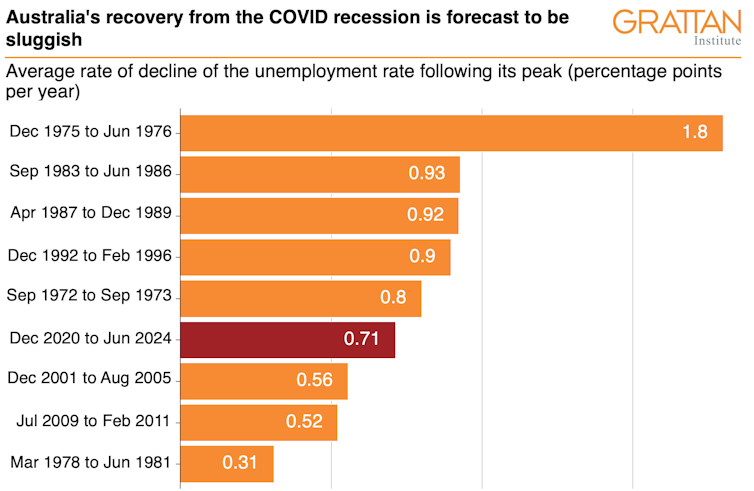

Yet Australia’s recovery from this COVID recession is officially forecast to be on the sluggish side, as our graph of the recovery in the unemployment rate after each of the past eight recessions and slowdowns shows.

The budget expects the unemployment rate to peak at 8% in December this year, but then take three-and-a-half years[2] to fall to 5.5% by mid-2024.

That’s an average decline of 0.71 percentage points per year in the unemployment rate.

Three-month moving average of unemployment rate used. The end date is the month with the lowest unemployment rate in the four years following the. recession peak, excluding any that occur after a subsequent recession. Excludes ’micro recoveries: defined as those with less than 6 months or 0.5 percentage points between peak and trough. Recessions defined using the Sahm Rule. OECD.Stat and Grattan calculations[3]

Three-month moving average of unemployment rate used. The end date is the month with the lowest unemployment rate in the four years following the. recession peak, excluding any that occur after a subsequent recession. Excludes ’micro recoveries: defined as those with less than 6 months or 0.5 percentage points between peak and trough. Recessions defined using the Sahm Rule. OECD.Stat and Grattan calculations[3]

In the 1990s recession – Australia’s most recent major recession – the unemployment rate peaked at 11.1% in late 1992, then fell to 8.3% by 1996.

That’s an average decline of 0.9 percentage points per year – a good deal faster than expected after this recession.

With, rather than ahead of, the pack

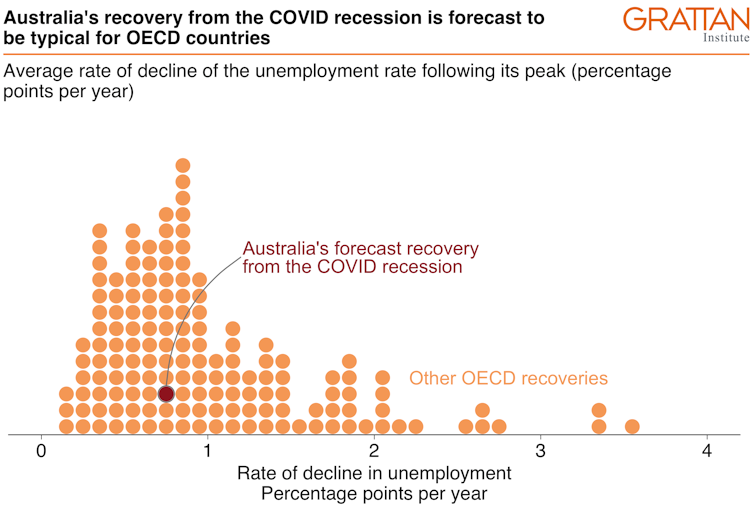

By the standards of past overseas recessions, our recovery is expected to be no more than typical.

We examined 150 past recessions in the countries that make up the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and found that typically unemployment falls by 0.85 percentage points per year – about the same as what Australia expects this time.

This analysis uses all the labour force data kept by the OECD – which in Australia’s case goes back to 1966.

Three-month moving average of unemployment rate used. The end date is the the month with the lowest unemployment rate in the four years following the recession peak, excluding any that occur after a subsequent recession. Excludes ’micro recoveries’, defined as those With less than 6 months or 0.5 percentage points between peak and trough. Recessions defined using the Sahm Rule. Source: OECD.Stat and Grattan calculations

Three-month moving average of unemployment rate used. The end date is the the month with the lowest unemployment rate in the four years following the recession peak, excluding any that occur after a subsequent recession. Excludes ’micro recoveries’, defined as those With less than 6 months or 0.5 percentage points between peak and trough. Recessions defined using the Sahm Rule. Source: OECD.Stat and Grattan calculations

The initial phase of the Australian recovery is forecast to be quite brisk, as you’d expect given the nature of this recession and the budget assumption that a COVID-19 vaccine will be found soon.

After peaking at 8% in late 2020, unemployment is expected to fall to 7.25% by mid-next year. That decline – 0.75 percentage points in 6 months, a 1.5-percentage-point annualised fall – is on the fast side.

We’re removing support too soon

But from there on, the recovery is forecast to stall, particularly in 2022-23 and 2023-24 when only 0.5 percentage points per year is expected to be knocked off the unemployment rate.

The budget papers show that support to date has kept unemployment much lower than it would have been.

Treasury believes that without it the unemployment rate would have peaked at about 13% instead of the predicted 8%.

Read more: High-viz, narrow vision: the budget overlooks the hardest hit in favour of the hardest hats[4]

Which raises the question: why isn’t the government being more ambitious and aiming to bring unemployment down faster?

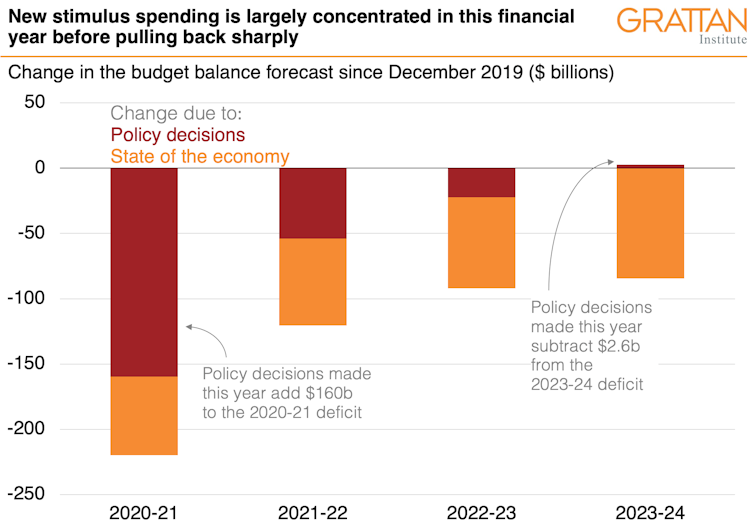

The rapid recovery in unemployment peters out from mid-2022 because, as this graph shows, the stimulus is set to be withdrawn quickly – the deficit is set to more or less halve next year, and then halve again over the following two years.

Policy decisions made this year actually subtract from the deficit by 2023-24.

Source: Budget 2020-21, Paper 1, Statement 2 And the stimulus is made up of measures not particularly likely to create jobs, such as income tax cuts (where much of the money is likely to be saved rather than spent) and transport infrastructure, which creates fewer jobs per dollar spent than services such as child care, health and aged care. We shouldn’t be content with a recovery that putters along at a below-average pace. Read more: Morrison is right. All governments will need to spend more to get us out of the crisis[5] We calculate that extra stimulus of about $50 billion over and above what was announced in the budget will be needed over the next two years to drive unemployment back down to 5%, a result that would kickstart wages growth nearly two years ahead of the government’s schedule. Some may appear in upcoming state budgets[6], but there’s no doubt the Treasurer has more work left to do. We could get unemployment down quickly Every year that unemployment remains too high is another year that Australians can expect close to zero real wages growth, and another year that Australians young and old will continue to confront a dearth of job opportunities. Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe said last week he wanted to achieve more than just “progress towards” full employment. For him and his board, addressing high unemployment was an “important national priority[7]”. It ought to also be an important government priority.

Source: Budget 2020-21, Paper 1, Statement 2 And the stimulus is made up of measures not particularly likely to create jobs, such as income tax cuts (where much of the money is likely to be saved rather than spent) and transport infrastructure, which creates fewer jobs per dollar spent than services such as child care, health and aged care. We shouldn’t be content with a recovery that putters along at a below-average pace. Read more: Morrison is right. All governments will need to spend more to get us out of the crisis[5] We calculate that extra stimulus of about $50 billion over and above what was announced in the budget will be needed over the next two years to drive unemployment back down to 5%, a result that would kickstart wages growth nearly two years ahead of the government’s schedule. Some may appear in upcoming state budgets[6], but there’s no doubt the Treasurer has more work left to do. We could get unemployment down quickly Every year that unemployment remains too high is another year that Australians can expect close to zero real wages growth, and another year that Australians young and old will continue to confront a dearth of job opportunities. Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe said last week he wanted to achieve more than just “progress towards” full employment. For him and his board, addressing high unemployment was an “important national priority[7]”. It ought to also be an important government priority. References

- ^ all about jobs (www.liberal.org.au)

- ^ three-and-a-half years (budget.gov.au)

- ^ OECD.Stat and Grattan calculations (blog.grattan.edu.au)

- ^ High-viz, narrow vision: the budget overlooks the hardest hit in favour of the hardest hats (theconversation.com)

- ^ Morrison is right. All governments will need to spend more to get us out of the crisis (theconversation.com)

- ^ upcoming state budgets (theconversation.com)

- ^ important national priority (www.rba.gov.au)

Authors: Brendan Coates, Program Director, Household Finances, Grattan Institute