Surplus before spending. Frydenberg's risky MYEFO strategy

- Written by Stephen Bartos, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

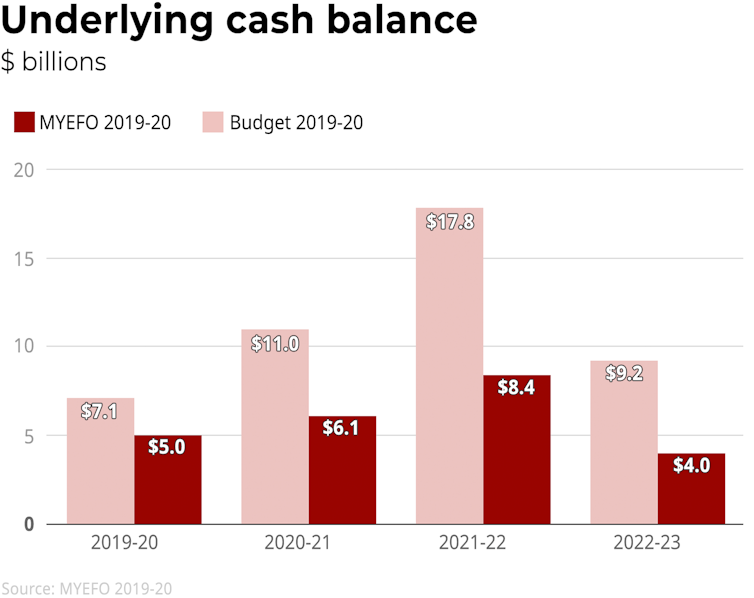

Today’s mid-year economic and fiscal outlook (MYEFO) continues to promise a small budget surplus[1] in 2019-20 and each of the following three years.

But the surpluses are very small, roughly half the size of those promised at the time of the April budget, and highly uncertain.

CC BY-ND[2]

The forecasts for economic growth and wages growth have been adjusted down, but are still optimistic, subject to downside risks, especially if international economic conditions deteriorate.

The lower wage growth forecast is an acknowledgement of the new reality that wage growth is not climbing and remains low.

Uncertainties abound

One key variable is iron ore prices: these affect both economic growth (gross domestic product) and company tax collections.

Recent high prices due in part to mining disasters in Brazil will not continue indefinitely.

Iron ore prices peaked in July at US$120 per tonne but are forecast to fall back to US$55 per tonne by the June quarter 2020.

The key determinant will be demand from China. Its steel mills might require more, or less, than expected.

MYEFO has a sensitivity analysis showing 2019-20 tax receipts could be lower than expected by A$0.8 billion or higher than expected by A$0.5 billion (and lower by $1.1b or higher by $1.3b in 2020-21) depending on how quickly prices fall.

Housing versus households

Another expected source of increased revenue is a recovery in capital city housing markets.

While this won’t have as large an impact on the Commonwealth as it will on the states which are reliant on stamp duties (see for example the recent NSW budget update[3]) the Commonwealth still benefits.

The assumption on households

that some of the recent weakness in consumption reflects timing factors and that the household saving ratio will fall as households increase their consumption in response to higher after-tax income

seems optimistic.

However the treasury acknowledges

there is a risk that consumers remain cautious and the fall in the household saving ratio is slower than expected.

It is possible that households will remain nervous about the future and save rather than spend; or that we are seeing deeper shifts in preferences away from consumer spending.

Surplus before spending

MYEFO includes previously-announced new spending on infrastructure projects, drought and aged care, but there were no major additional announcements.

This is in line with the government’s determination to have a surplus this year, even if smaller than expected at budget time.

The underlying cash surplus of $5.0 billion forecast for 2019-20 is indeed small - a fraction under 1% of the total receipts number, $502.5.

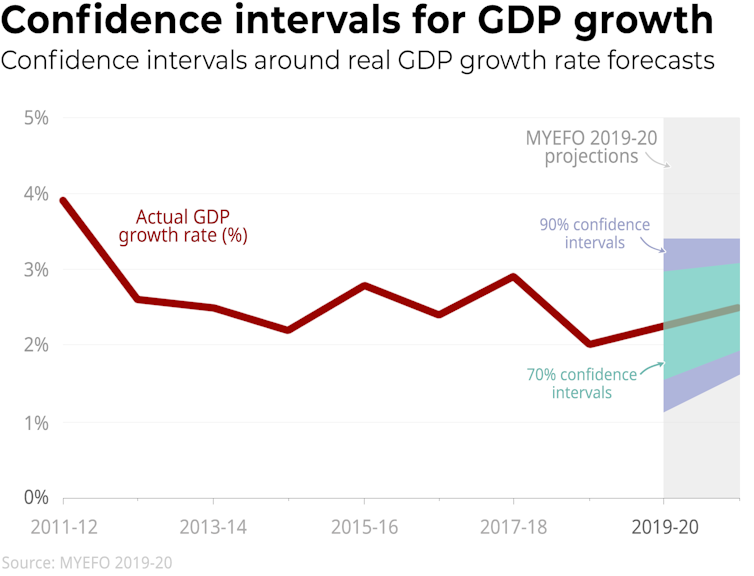

MYEFO graphs the confidence we can have in the surplus forecasts: there is considerable uncertainty.

CC BY-ND[2]

The forecasts for economic growth and wages growth have been adjusted down, but are still optimistic, subject to downside risks, especially if international economic conditions deteriorate.

The lower wage growth forecast is an acknowledgement of the new reality that wage growth is not climbing and remains low.

Uncertainties abound

One key variable is iron ore prices: these affect both economic growth (gross domestic product) and company tax collections.

Recent high prices due in part to mining disasters in Brazil will not continue indefinitely.

Iron ore prices peaked in July at US$120 per tonne but are forecast to fall back to US$55 per tonne by the June quarter 2020.

The key determinant will be demand from China. Its steel mills might require more, or less, than expected.

MYEFO has a sensitivity analysis showing 2019-20 tax receipts could be lower than expected by A$0.8 billion or higher than expected by A$0.5 billion (and lower by $1.1b or higher by $1.3b in 2020-21) depending on how quickly prices fall.

Housing versus households

Another expected source of increased revenue is a recovery in capital city housing markets.

While this won’t have as large an impact on the Commonwealth as it will on the states which are reliant on stamp duties (see for example the recent NSW budget update[3]) the Commonwealth still benefits.

The assumption on households

that some of the recent weakness in consumption reflects timing factors and that the household saving ratio will fall as households increase their consumption in response to higher after-tax income

seems optimistic.

However the treasury acknowledges

there is a risk that consumers remain cautious and the fall in the household saving ratio is slower than expected.

It is possible that households will remain nervous about the future and save rather than spend; or that we are seeing deeper shifts in preferences away from consumer spending.

Surplus before spending

MYEFO includes previously-announced new spending on infrastructure projects, drought and aged care, but there were no major additional announcements.

This is in line with the government’s determination to have a surplus this year, even if smaller than expected at budget time.

The underlying cash surplus of $5.0 billion forecast for 2019-20 is indeed small - a fraction under 1% of the total receipts number, $502.5.

MYEFO graphs the confidence we can have in the surplus forecasts: there is considerable uncertainty.

CC BY-ND[4]

Governments can always introduce either spending cuts or additional revenue raising measures in pursuit of a surplus.

The question is why. It is puzzling that having a surplus has become a sign of good economic management.

Surplus for the sake of surplus

Arguably what is more important is people’s real incomes, whether their chance of unemployment is rising or falling, whether they will be looked after in old age, have their health needs met, and be able to offer their children a good education.

There is a good argument against debt – government debt has to be paid off before the money spent servicing it can be spend on other needs, and excessive debt exposes a country to risk.

Read more:

5 things MYEFO tells us about the economy and the nation’s finances[5]

Within reasonable bounds though, neither ratings agencies nor international financial markets care if a budget is $5b in surplus or $5b in deficit – these are for all intents and purposes the same number in terms of the government’s impact on the economy.

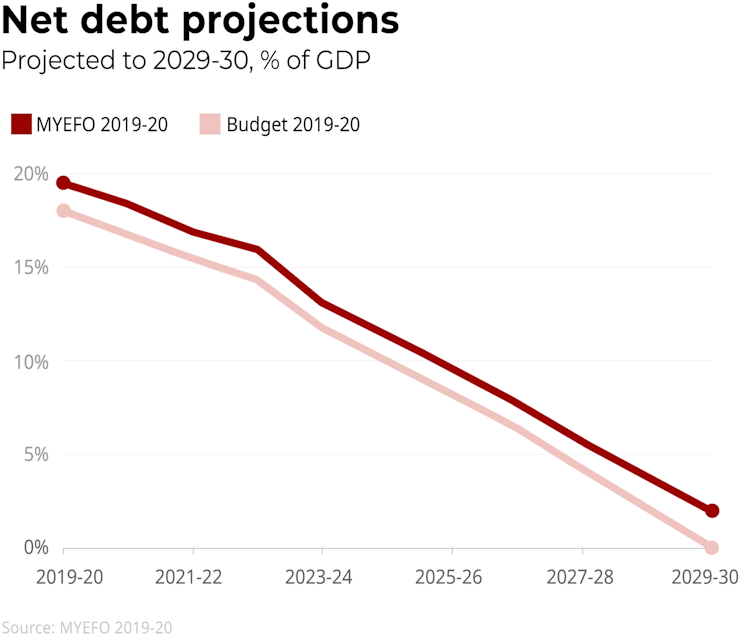

The government is no longer projecting net debt will fall to zero by 2029-30 – instead, it will fall to 1.8% of GDP (still much lower than the 2019-20 net debt of $392.3 billion or 19.5% of GDP).

CC BY-ND[4]

Governments can always introduce either spending cuts or additional revenue raising measures in pursuit of a surplus.

The question is why. It is puzzling that having a surplus has become a sign of good economic management.

Surplus for the sake of surplus

Arguably what is more important is people’s real incomes, whether their chance of unemployment is rising or falling, whether they will be looked after in old age, have their health needs met, and be able to offer their children a good education.

There is a good argument against debt – government debt has to be paid off before the money spent servicing it can be spend on other needs, and excessive debt exposes a country to risk.

Read more:

5 things MYEFO tells us about the economy and the nation’s finances[5]

Within reasonable bounds though, neither ratings agencies nor international financial markets care if a budget is $5b in surplus or $5b in deficit – these are for all intents and purposes the same number in terms of the government’s impact on the economy.

The government is no longer projecting net debt will fall to zero by 2029-30 – instead, it will fall to 1.8% of GDP (still much lower than the 2019-20 net debt of $392.3 billion or 19.5% of GDP).

CC BY-ND[6]

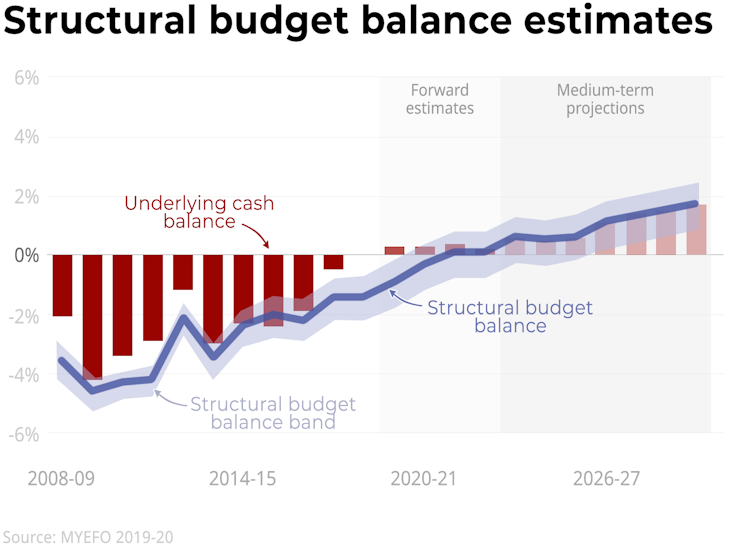

This is however a heroic projection, based on estimates of the structural budget position that are unlikely to be be realised.

The structural estimates (estimates of where the budget would be were it not for whatever was happening in the economy at the time) have surpluses growing every year up to 2029-30; an unlikely scenario in the face of an ageing population together with other pressures on government spending.

The impact of ageing will be analysed in more depth in the next Intergenerational Report to be produced by Treasury.

CC BY-ND[6]

This is however a heroic projection, based on estimates of the structural budget position that are unlikely to be be realised.

The structural estimates (estimates of where the budget would be were it not for whatever was happening in the economy at the time) have surpluses growing every year up to 2029-30; an unlikely scenario in the face of an ageing population together with other pressures on government spending.

The impact of ageing will be analysed in more depth in the next Intergenerational Report to be produced by Treasury.

CC BY-ND[7]

This may explain why the Treasurer today announced the next five-yearly Intergenerational Report[8] will not be published in March next year as scheduled, but held over until July, after the budget and after the report of the government’s retirement incomes inquiry[9].

There are several gaps in the estimates of spending.

Likely costs left out

There is no provision for additional spending on the new services delivery model, Services Australia, previously known as the department of human services, which runs Centrelink. Modelled on Services NSW, which offers a better customer experience, it will be expensive.

Services NSW meets its costs by charging other government agencies, spreading costs across government. There is less scope for this in the Commonwealth, and therefore a potentially higher direct call on the budget.

Read more:

The dirty secret at the heart of the projected budget surplus: much higher tax bills[10]

Although the announced funding for aged care is included, most observers of the work of the aged care royal commission expect this is only a first instalment.

Other pressures on the budget are not included for technical reasons. For example, possible future disasters are not included in the forward estimates because they are unpredictable.

Should climate change make Australia more prone to frequent and costly disasters, future budgets will face additional pressure.

There are thus numerous uncertainties around MYEFO – among them the growth path of the Chinese economy and its impact on iron ore prices, consumer demand, wages, spending pressures.

The projections might be achieved if all goes well – but there are considerable risks all will not.

CC BY-ND[7]

This may explain why the Treasurer today announced the next five-yearly Intergenerational Report[8] will not be published in March next year as scheduled, but held over until July, after the budget and after the report of the government’s retirement incomes inquiry[9].

There are several gaps in the estimates of spending.

Likely costs left out

There is no provision for additional spending on the new services delivery model, Services Australia, previously known as the department of human services, which runs Centrelink. Modelled on Services NSW, which offers a better customer experience, it will be expensive.

Services NSW meets its costs by charging other government agencies, spreading costs across government. There is less scope for this in the Commonwealth, and therefore a potentially higher direct call on the budget.

Read more:

The dirty secret at the heart of the projected budget surplus: much higher tax bills[10]

Although the announced funding for aged care is included, most observers of the work of the aged care royal commission expect this is only a first instalment.

Other pressures on the budget are not included for technical reasons. For example, possible future disasters are not included in the forward estimates because they are unpredictable.

Should climate change make Australia more prone to frequent and costly disasters, future budgets will face additional pressure.

There are thus numerous uncertainties around MYEFO – among them the growth path of the Chinese economy and its impact on iron ore prices, consumer demand, wages, spending pressures.

The projections might be achieved if all goes well – but there are considerable risks all will not.

References

- ^ small budget surplus (budget.gov.au)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ NSW budget update (www.budget.nsw.gov.au)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ 5 things MYEFO tells us about the economy and the nation’s finances (theconversation.com)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Intergenerational Report (treasury.gov.au)

- ^ retirement incomes inquiry (theconversation.com)

- ^ The dirty secret at the heart of the projected budget surplus: much higher tax bills (theconversation.com)

Authors: Stephen Bartos, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

Read more http://theconversation.com/surplus-before-spending-frydenbergs-risky-myefo-strategy-128092