Why we distrust the consumer price index

- Written by Richard Holden, Professor of Economics and PLuS Alliance Fellow, UNSW

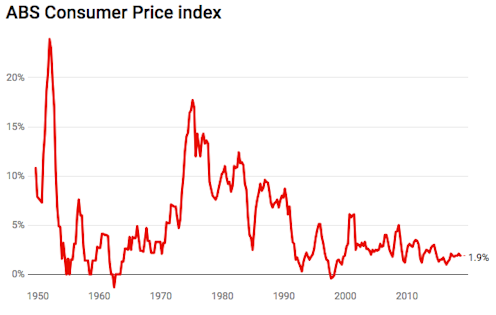

Officially, Australia’s rate of inflation is 1.9%[1].

It’s the lowest it has been on a sustained basis since the 1950s and early 1960s[2].

But try to tell that to anyone and they will laugh at you, or worse.

The Bureau of Statistics is careful to say that the consumer price index isn’t a measure of living costs[3].

It creates that slightly differently, producing a collection of less-reported indexes[4] that were updated this week.

On these measures, over the past year living costs have climbed 2% for households headed by an employee, 2.2% for households headed by Australians on most types of benefits, 2.3% for households headed by age pensioners, and also 2.3% for households headed by self-funded retirees.

The main difference between the consumer price index and the living cost indexes is that “living costs” include interest paid on mortgages whereas “consumer prices” do not.

Regardless, most of us would be pretty certain that even on these measures, what’s reported is too low.

We’re irrational

In part, this is because we are not rational. As Nobel Laureate Richard Thaler has pointed out[5], we often engage in “mental accounting”.

In general this means we notice losses more than gains. In this context, it means we focus more on the things that have gone up in price than on those that have gone down or remained unchanged.

Also, our mental basket of goods is generally not the same as the basket of goods the bureau measures, even though it should be.

It’s not our basket

Four times a year in multiple locations throughout each capital city the bureau attempts to collect information about the prices of the thousands of goods (and some services) that make the “basket” it thinks represent they typical household’s purchases.

The basket is divided into about 100 subgroups; things such as bread, milk, eggs, fruit, men’s footwear, women’s footwear, men’s clothes, women’s clothes, restaurant meals, electricity and so on.

Because it can’t price everything, it zeros in on a few representative items[6] within each category.

For meat and fish the ABS includes beef sausages (1kg) and pink salmon (210g can). For processed fruit and vegetables it includes sliced pineapple (450g can) and frozen peas (500g pkt).

If you buy something different, the exact changes in the prices you pay won’t be fed into either the consumer price index or your living cost index, but the indexes are likely to move in line with your living costs in any case.

Things get left out

Many things are missing from the index, among them recreational drugs, gambling and prostitution.

Being bean counters, rather than priests, the bureau says it excludes these sorts of items on practical rather than moral grounds[7].

Gambling is excluded as it is difficult to establish the service or utility that households derive from gambling, and thus to determine an appropriate price measure. Recreational drugs and prostitution are both excluded as it is very difficult and indeed dangerous to obtain estimates of prices and expenditures, or to measure quality change.

Other things are excluded because their prices are deemed to be too volatile. The price of bank deposits and loans was removed from the main index[8] a few years back.

And goods keep getting better

Where our views about prices are most likely to differ from the bureau’s is where goods get better.

The bureau factors quality improvements into the measures prices it reports. If, for instance, your next mobile phone costs as much as your last one but includes extra features such as more memory or an improved camera, the ABS will report that it has fallen in price.

Read more: Moore's Law is 50 years old but will it continue?[9]

This sort of adjustment for quality makes sense when adjusting down the price of a can of baked beans because it has been replaced by one slightly bigger, but is a grey area when it comes to improved features.

If the speed of the chip on your next laptop doubles, does that really mean the laptop is twice as good as the old one and should be said to have halved in price? Or should its price be recorded as having fallen by a lesser amount, or not at all seeing as the price hasn’t changed and it remains a standard laptop?

Often older models with lesser features are often no longer available. It’s impossible to buy a cheaper replacement.

The CPI is infrequent

The Reserve Bank is worried about the frequency of the index[10]. It comes out only once a quarter, and up to a month after the quarter has finished.

Every developed country other than Australia and New Zealand releases its index monthly[11].

Given that the bank considers changing interest rates once every month, and given that the consumer price index is one of the two key measures it uses to guide its decisions (the other is the unemployment rate), a quarterly index leaves it somewhat in the dark and (when things are changing fast) potentially dangerously misled.

The bureau responds[12] that it is prepared to release its index monthly, if it is paid to do it.

The ABS is persuaded there would be a significant benefit from more timely and responsive economic management if a CPI of equivalent quality to the current quarterly index were available monthly. Additional funding will be required to meet the costs involved in compiling a monthly index.

It’s just what we need – bureaucratic blackmail.

But it’s improving

On the positive side, new technologies have allowed more accurate price collection to make the index more precise. A key innovation is the rise of so-called “scanner data”, tracking expenditures at checkouts based on the prices people actually pay.

Scanner data has been used since 2014 and is now responsible for about one quarter of the prices reported. Field officers compile much of the rest using hand-held devices to type in prices they read off supermarket shelves[13].

The move to scanner data was spearheaded by the work of my UNSW School of Economics colleague Professor Kevin Fox[14].

Read more: A cashless society and the five forms of mobile payment that will get us there[15]

There is a prospect of it becoming more widespread as more and more purchases are made with debit and credit cards and with point-of-sale software on devices such as tablets at coffee shops.

And important

Whether or not we like what it says, the consumer price index is important and lies behind much of what we do.

A whole range of government payments and duties are indexed to it – these change when the consumer price index changes. Benefits such as Newstart and family payments are indexed as are excise duties such as those on petrol and beer.

Even the private sector relies on the consumer price index to adjust payments under contracts such as rental agreements or construction charges.

Read more: Joe Hockey's user pays plan for the ABS doesn't add up[16]

Collecting it is an enormous and painstaking exercise.

Governments of both stripes would do well to remember that when next they think of cutting the bureau’s budget.

References

- ^ is 1.9% (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ since the 1950s and early 1960s (www.datawrapper.de)

- ^ isn’t a measure of living costs (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ less-reported indexes (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ Richard Thaler has pointed out (faculty.chicagobooth.edu)

- ^ representative items (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ practical rather than moral grounds (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ removed from the main index (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ Moore's Law is 50 years old but will it continue? (theconversation.com)

- ^ the frequency of the index (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ monthly (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ responds (www.ausstats.abs.gov.au)

- ^ hand-held devices to type in prices they read off supermarket shelves (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ Professor Kevin Fox (theconversation.com)

- ^ A cashless society and the five forms of mobile payment that will get us there (theconversation.com)

- ^ Joe Hockey's user pays plan for the ABS doesn't add up (theconversation.com)

Authors: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics and PLuS Alliance Fellow, UNSW

Read more http://theconversation.com/vital-signs-why-we-distrust-the-consumer-price-index-106150