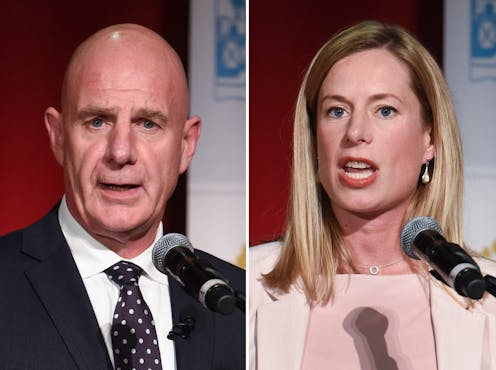

As Tasmanians head to the polls, Liberal Premier Peter Gutwein hopes to cash in on COVID management

- Written by Michael Lester, PhD candidate, University of Tasmania

Tasmanian Liberal Premier Peter Gutwein is gambling on an early election to cash in on his government’s popularity due to its management of the COVID pandemic. It is a reasonable strategy, given how voters in Queensland[1] and Western Australia[2] have rewarded their governments in recent months.

Gutwein announced the May 1 election on March 26 – a year earlier than it is due. This was possible because, while Tasmania has a four-year maximum term, it does not have a fixed term, unlike all other states and territories.

In 2018 the Liberals, under then-Premier Will Hodgman, were returned to government[3] with a bare majority of 13 of the 25 members of the lower house. Gutwein took over the premiership following Hodgman’s resignation[4] in January 2020.

Over the past three years, the majority government has at times looked shaky. This was typified by maverick Liberal Clark MP Sue Hickey winning the speakership ballot[5] with the support of Labor and the Greens against her party’s candidate. She has since voted against government legislation and policy on a number of policy and social reform issues.

Five days before calling the election Gutwein informed Hickey she would not get Liberal re-endorsement for the next election. She resigned[6] from the party, putting the government into minority.

Having engineered a minority government and, despite written assurances from Hickey and ex-Labor, independent MP Madeleine Ogilvie on confidence and supply, Gutwein then called the election to secure “stable majority government”. His reasoning was that this would keep Tasmania in safe hands for ongoing management of COVID.

Read more: Morrison's ratings take a hit in Newspoll as Coalition notionally loses a seat in redistribution[7]

A few days later, Ogilvie was endorsed[8] as a Liberal candidate for Clark. This underlined the artificiality of the minority government argument.

Under Tasmania’s Hare-Clark proportional electoral system[9], five members are elected to each of five multi-member seats. These are Bass in the north, Braddon in the north west, Clark and Franklin in the greater Hobart and southern region, and the sprawling Lyons across the middle of the state.

Going into this election, the Liberals had 12 seats, Labor nine, Tasmanian Greens two and there were two independents.

In March 2020, before the pandemic, Labor leader Rebecca White was matching first Hodgman and then Gutwein as preferred premier.

However, that changed after Gutwein declared a state of emergency[10] and the “toughest border restrictions in Australia”.

Like his counterparts in Queensland and WA, the hard-line stance was widely interpreted as keeping the state safe. Gutwein polled as high as 70% as preferred premier in opinion polls[11] throughout 2020.

The election announcement caught Labor unprepared. The start of its campaign was sidetracked by factional battles over preselection of high-profile Kingborough Mayor Dean Winter[12] for the seat of Franklin. It also had to deal with the resignation[13] of state ALP president Ben McGregor from the campaign over crude text messages he sent to a female colleague some years ago.

The Liberals also have had their share of problems. Franklin candidate Dean Ewington was forced to resign[14] when it was revealed he had attended anti-lockdown rallies against Gutwein’s policy. Ex-minister and now Braddon candidate Adam Brooks also faces police charges[15] over alleged contraventions of gun storage law.

Tasmania has has three minority governments in the modern era. These are the 1989 Labor-Green Accord[16] government, the 1996 Liberal minority government[17] and the 2010 Labor-Green quasi-coalition[18] government. In each case voters punished the major governing party at the following election.

Consequently, the prospect of a hung parliament is always a central election issue in this state. Both Labor and the Liberals have pledged to govern in majority or not at all. However, in their one campaign debate to date, both Gutwein and White indicated they would resign the leadership rather than lead a minority government. This seems to leave open the door for their replacements to take up negotiations to form government.

Federal issues and federal political leaders have had a minimal impact on the Tasmanian election. So far, Prime Minister Scott Morrison has not visited the state during the campaign, even for the Liberal campaign launch. Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese has visited twice, including for Labor’s launch.

While Tasmania’s economy has held up surprisingly well during the pandemic – due in no small part to Commonwealth JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments – the end of those payments is likely to have a negative impact on the state’s economy. Some have pointed to this[19] as an underlying reason for going to an election early.

Concerns about delays to the roll-out of COVID vaccinations and the possible distraction from the key state Liberal campaign theme of management of the pandemic may be another reason for keeping federal ministers away.

Read more: WA election could be historical Labor landslide, but party with less than 1% vote may win upper house seat[20]

For its part, Labor has campaigned on state Liberal failure to reduce hospital[21] and housing waiting lists and the lack of action on a range of key infrastructure development promises made at the 2018 election. The opposition has also raised concerns about future budget spending cuts[22] to fund high-cost COVID economic stimulus measures, TAFE privatisation[23] and delays in replacing[24] the Spirit of Tasmania ferries, which are vital for interstate transport, tourism and freight.

The Greens and key high-profile independent candidates such as Hickey and popular Glenorchy Mayor Kristie Johnston in Clark have raised concerns[25] about government secrecy, ministerial accountability and the state’s weak laws on political donations and, associated with that, poker machine licensing reforms[26].

There have been no public political opinion polls so far during this campaign. However, successive surveys by Tasmanian pollsters EMRS throughout 2020 placed the Liberals as likely to win more than 52%[27] of the vote state-wide.

Since, historically, a party winning anything over 48% is likely to secure majority government in Tasmania, if those polls are reflected in the election outcome on May 1, another majority Liberal government seems likely.

References

- ^ Queensland (theconversation.com)

- ^ Western Australia (theconversation.com)

- ^ returned to government (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ Hodgman’s resignation (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ winning the speakership ballot (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ resigned (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ Morrison's ratings take a hit in Newspoll as Coalition notionally loses a seat in redistribution (theconversation.com)

- ^ was endorsed (www.examiner.com.au)

- ^ Tasmania’s Hare-Clark proportional electoral system (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ declared a state of emergency (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ opinion polls (www.examiner.com.au)

- ^ high-profile Kingborough Mayor Dean Winter (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ the resignation (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ forced to resign (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ also faces police charges (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ 1989 Labor-Green Accord (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ 1996 Liberal minority government (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ 2010 Labor-Green quasi-coalition (theconversation.com)

- ^ pointed to this (www.themercury.com.au)

- ^ WA election could be historical Labor landslide, but party with less than 1% vote may win upper house seat (theconversation.com)

- ^ Liberal failure to reduce hospital (taslabor.com)

- ^ future budget spending cuts (taslabor.com)

- ^ TAFE privatisation (www.theadvocate.com.au)

- ^ delays in replacing (taslabor.com)

- ^ raised concerns (www.themercury.com.au)

- ^ poker machine licensing reforms (www.themercury.com.au)

- ^ as likely to win more than 52% (www.emrs.com.au)