As our research has previously revealed, the man who attacked two mosques in Christchurch in 2019, killing 51 people, posted publicly online for five years before his terrorist atrocity.

Here we provide further information about Brenton Tarrant’s posting. This article has two main goals.

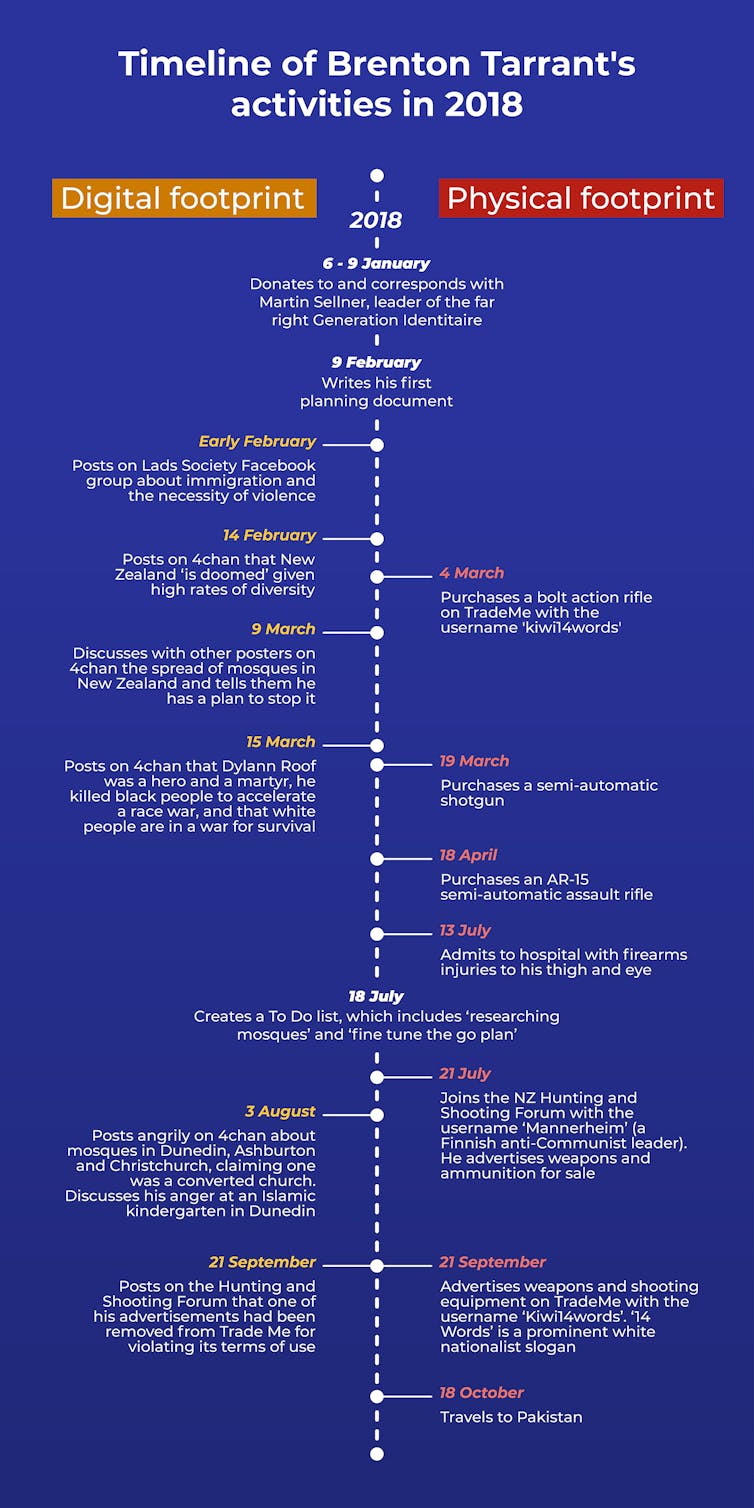

First, by placing his online posting against his other online and offline activities, we gain a far more complete picture of the path to his attack.

Second, we want to show how his online community played a role in his radicalisation. This is important, as the same can happen to others immersed in that community.

In combining his online and offline activity here we do not seek to attribute blame to those who might have been expected to detect this behaviour. It is exceptionally difficult to identify terrorists online.

And yet, history is full of difficult problems that have been overcome. We use the benefit of hindsight to provide greater understanding of Tarrant’s pathway than has previously been available.

The aim is to prevent similar attacks by better understanding how such people act and how they might be detected.

Read more:

Christchurch terrorist discussed attacks online a year before carrying them out, new research reveals

Words and deeds

In the timeline below, we focus on Tarrant’s activity in 2018, following his first visit to Dunedin’s Bruce Rifle Club on December 14 2017, until his final overseas trip in October. It is for this period that we have the most comprehensive online posting history.