Young people may decide the outcome of the Voice referendum – here's why

- Written by Intifar Chowdhury, Associate Lecturer, School of Politics and International Relations, Australian National University

A referendum on a First Nations Voice to Parliament is set to be held in the second half of this year. Australians will be asked if they agree to a constitutional amendment to give First Nations people a voice in government decisions that directly affect them. This body aims to circumvent complicated bureaucracy, address consistently poor life outcomes, and improve the services and support of Indigenous communities in Australia.

Given young Australians, mostly progressive and most engaged in issue-based politics, helped swing the 2022 election[1], it is likely their support will be crucial to the “yes” campaign.

Why is youth support crucial?

Historically, Australians have been reluctant to change the Constitution. Only eight out of 44 referendums[2] carried, with no successful constitutional change since 1977. For the referendum to be successful, the proposed alteration must pass by a “double majority”: this means a majority of voters nationwide and a majority of voters in a majority of the states (that is, at least four out of six states).

Read more: Changing the Australian Constitution is not easy. But we need to stop thinking it's impossible[3]

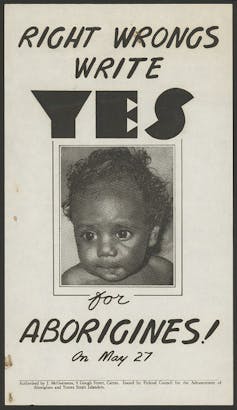

The 1967 referendum had the highest ‘yes’ vote in history, garnering over 90% support. State Library of South AustraliaBut referendums are not bound to fail. Since the referendum is inherently an issue-based vote, the success in the past depended heavily on the issue. Previously, campaigns have been more successful when they focused on principles or outcomes, rather than on the technical and procedural issues concerning particular amendments.

For example, the 1967 referendum on Indigenous constitutional recognition scored[4] the highest percentage of votes (90.77%) in favour of any referendum. In contrast, the 1999 referendum to change Australia from a constitutional monarchy to a republic did not garner majority support from any state.

Since young Australians are more inclined to policy voting[5] than partisan voting, educating young people about the issue will be vital for the Voice referendum. Further, young voters may help inform[6] older non-Indigenous people – the group most likely to vote “no” in the referendum.

Read more: What will young Australians do with their vote – are we about to see a 'youthquake'?[7]

What’s in it for the young person?

For a young Indigenous Australian, an Indigenous Voice to Parliament is important for two key reasons.

First, the national Voice would have a youth advisory group[8] – as one of two permanent groups – that is expected to focus on improving Indigenous peoples’ educational, psychological, health, economic and other social outcomes. Second, and more broadly, it gives a voice to their communities, which all levels of government are obliged to consult.

Read more: The Voice referendum: how did we get here and where are we going? Here's what we know[9]

For a non-Indigenous young person, the proposed body will play an important role in educating and explaining what has happened and is still happening to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Cobble Cobble woman Allira Davis, co-chair of the Uluru Youth Dialogue, said[10] the essential but “harsh business of truth-telling” has been lacking in national conversations, although this is “changing among younger generations of non-Indigenous Australians”.

Why are young people likely to vote in favour?

In a recent nationally representative survey, Australians were asked: “If a referendum were held to recognise Indigenous Australians in the Constitution, would you support or oppose such a change to the Constitution?” Young Australians, aged 18-34, strongly supported a constitutional amendment for Indigenous recognition.

Data from the 2022 Australian Election Study (AES)[11] show that, compared to older age groups, the youngest voter group is most likely to “strongly support” and least likely to “strongly oppose” the referendum.

An analysis of the latest enrolment data[12] from the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) shows that millennials and Gen Z make up about 43% of the electorate[13]. This indicates a major generational replacement as the polls are being populated with more progressive, younger voters.

Read more: Will multicultural Australians support the Voice? The success of the referendum may hinge on it[14]

Although lifecycle theories oppose this idea and predict people become more conservative as they age, this may not apply to millennials and younger people. Evidence from the AES suggests millennials are not becoming more conservative[15] as they get older and are sticking with left-of-centre parties.

Extending the findings in the figure above, and analysing the AEC enrolment data, it is evident that a majority of states (except Tasmania) reflect the high percentage of youth population. That means there is a fair chance mostly progressive young people and younger generations may be driving the “yes” vote in the referendum.

But there is still opposition

Some young people, especially those affiliated with the Liberal Party, raise mixed views[16] about the referendum, demanding more clarity[17] on the proposal in its current form. That is, most do support the need to recognise the historical wrong done to Indigenous communities, but they are not supportive of the approach because, as a young Liberal said[18], isolating a group for benefits or harm “is inherently wrong and should be opposed”.

Plus, there are both right and left-wing opponents[19] of the Voice. Therefore, we must be cautious in thinking a progressive individual will definitely vote “yes”.

Historically, one of the biggest threats to referendums has been a “no” campaign run by a major political party[20]. A strong opposition, or lack of bipartisan approval[21], may render voters vulnerable to scare campaigns[22].

Young people – mostly those who haven’t yet had a chance to participate in a referendum – already have a low level of understanding of constitutional matters. But given they are more likely to strongly support the Indigenous cause than their older counterparts, a transparent and thorough public education campaign is much needed to gather informed youth support.

References

- ^ swing the 2022 election (theconversation.com)

- ^ eight out of 44 referendums (www.aec.gov.au)

- ^ Changing the Australian Constitution is not easy. But we need to stop thinking it's impossible (theconversation.com)

- ^ scored (www.aec.gov.au)

- ^ inclined to policy voting (theconversation.com)

- ^ young voters may help inform (www.canberratimes.com.au)

- ^ What will young Australians do with their vote – are we about to see a 'youthquake'? (theconversation.com)

- ^ youth advisory group (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ The Voice referendum: how did we get here and where are we going? Here's what we know (theconversation.com)

- ^ said (www.canberratimes.com.au)

- ^ Australian Election Study (AES) (australianelectionstudy.org)

- ^ latest enrolment data (www.aec.gov.au)

- ^ 43% of the electorate (theconversation.com)

- ^ Will multicultural Australians support the Voice? The success of the referendum may hinge on it (theconversation.com)

- ^ not becoming more conservative (www.afr.com)

- ^ mixed views (www.afr.com)

- ^ more clarity (www.afr.com)

- ^ said (www.afr.com)

- ^ left-wing opponents (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ “no” campaign run by a major political party (theconversation.com)

- ^ bipartisan approval (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ vulnerable to scare campaigns (theconversation.com)