Exports and immigrants have masked Australia's poor R&D record. Here are some simple fixes

- Written by George A. Tanewski, Professor in Accounting, Deakin University

Australia’s long run of economic growth from the early 1990s to early 2020 inspired much boasting by incumbent politicians.

But behind the hubris and headlines lies a less flattering story — about Australia riding a wave of dumb luck, with exports to China and relatively high levels of immigration masking mundane economic performance.

The most obvious expression of this is investment by Australia’s private sector — overwhelmingly made up of small-to-medium size (SME) enterprises — in innovation.

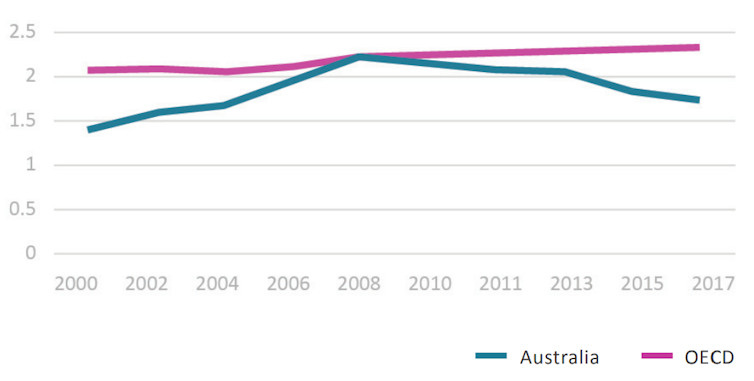

The sector’s expenditure on research & development — measured as a percentage of GDP — is middling at best. After increasing to match the OECD average[1] of about 2.2% in 2008, it slipped to less than 1.8% in 2017. This compares with more than 4% for the two top-ranking nations, Israel and South Korea, and more than 3% for Taiwan, Sweden, Japan and Germany.

But with some fine-tuning of policies and incentives in this area, our analysis[2] suggests the federal government could turn around Australia’s performance on research and development within a decade.

Read more: To become an innovation nation, we really need to think smaller[3]

We can’t rely on China and immigration

Australia’s ability to keep relying on booming Chinese demand for minerals and the stimulatory effect of high immigration rates pushing up GDP is unclear at best.

Though exports to China are at a record high[4], this is overwhelmingly due to demand from Chinese steel makers for iron ore, and to a lesser extent wool. By most other measures, however, our relationship with China is troubled.

Read more: Morrison's dilemma: Australia needs a dual strategy for its trade relationship with China[5]

Housing unaffordability and congestion in our major cities means there will be political pressure to moderate post-COVID immigration rates.

Of all the alternative ways to improve our economic security, the potential of small and medium size businesses to innovate stands out.

Tax incentives

Since 2011 the federal government’s primary mechanism to encourage companies to invest in innovation has been its research and development tax incentive scheme[6]. This provides tax offsets for eligible R&D activities. It has some solid features, in common with schemes in other countries. But the statistics suggest it has not delivered.

Australia’s R&D expenditure as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) declined from 2.18% in 2010 to 1.79% in 2017[7]. The OECD average from 2000 to 2017 was 2.34%.

Business R&D expenditure as a percentage of GDP

Post COVID Policy Options to Enhance Australia’s Innovation Capabilities Small Business White Paper 2021

This failure — and the dire implications for Australia’s long-term economic prosperity — prompted our research team to investigate policy fixes.

How to increase R&D

One clear area for improvement is businesses tapping into the strong research culture of our world-class universities and other government-funded research organisations. A wealth of Australian expertise remains locked within the walls of our research institutions.

Read more:

Want more research commercialisation? Then remove the barriers and give academics real incentives to do it[8]

Some problems are specific to industries. For example, the government’s R&D incentives have excluded software companies from eligibility for incentives. This has arguably been both unfair and unwise, constraining the growth of a potentially huge local industry — as the success of companies such as Atlassian and Canva demonstrate.

Changes to the tax incentives scheme introduced in July, designed to increase incentives for R&D generally, will have the perverse effect of reducing incentives for many smaller and medium-sized companies in the medium to longer term (more than five years).

But there is cause for hope. Australia’s performance on innovation can be turned around within about ten years through judicious fine-tuning of federal industry policies.

These include:

reversing the July changes to the R&D tax incentives scheme

reimbursing R&D offsets quarterly rather than annually, a small administrative change that would help the cash flow of small businesses, enabling them to more readily invest in R&D

increasing financial incentives to companies for research collaboration with research institutions.

One idea to encourage collaboration with research institutions is trialling “innovation vouchers”. These provide conditional funding for R&D, being redeemable only through collaborating with a university or other publicly funded research institution. Such vouchers have already been trialled in the UK and the Netherlands, with strong evidence they stimulate R&D activity by small to medium-sized businesses.

These proposals, in combination with others detailed in our report[9], could help unlock a potentially rich source of growth and prosperity.

Post COVID Policy Options to Enhance Australia’s Innovation Capabilities Small Business White Paper 2021

This failure — and the dire implications for Australia’s long-term economic prosperity — prompted our research team to investigate policy fixes.

How to increase R&D

One clear area for improvement is businesses tapping into the strong research culture of our world-class universities and other government-funded research organisations. A wealth of Australian expertise remains locked within the walls of our research institutions.

Read more:

Want more research commercialisation? Then remove the barriers and give academics real incentives to do it[8]

Some problems are specific to industries. For example, the government’s R&D incentives have excluded software companies from eligibility for incentives. This has arguably been both unfair and unwise, constraining the growth of a potentially huge local industry — as the success of companies such as Atlassian and Canva demonstrate.

Changes to the tax incentives scheme introduced in July, designed to increase incentives for R&D generally, will have the perverse effect of reducing incentives for many smaller and medium-sized companies in the medium to longer term (more than five years).

But there is cause for hope. Australia’s performance on innovation can be turned around within about ten years through judicious fine-tuning of federal industry policies.

These include:

reversing the July changes to the R&D tax incentives scheme

reimbursing R&D offsets quarterly rather than annually, a small administrative change that would help the cash flow of small businesses, enabling them to more readily invest in R&D

increasing financial incentives to companies for research collaboration with research institutions.

One idea to encourage collaboration with research institutions is trialling “innovation vouchers”. These provide conditional funding for R&D, being redeemable only through collaborating with a university or other publicly funded research institution. Such vouchers have already been trialled in the UK and the Netherlands, with strong evidence they stimulate R&D activity by small to medium-sized businesses.

These proposals, in combination with others detailed in our report[9], could help unlock a potentially rich source of growth and prosperity.

References

- ^ the OECD average (dx.doi.org)

- ^ our analysis (www.deakin.edu.au)

- ^ To become an innovation nation, we really need to think smaller (theconversation.com)

- ^ a record high (www.theaustralian.com.au)

- ^ Morrison's dilemma: Australia needs a dual strategy for its trade relationship with China (theconversation.com)

- ^ research and development tax incentive scheme (www.ato.gov.au)

- ^ 1.79% in 2017 (data.oecd.org)

- ^ Want more research commercialisation? Then remove the barriers and give academics real incentives to do it (theconversation.com)

- ^ in our report (www.deakin.edu.au)

Authors: George A. Tanewski, Professor in Accounting, Deakin University