Great approach, weak execution. Economists decline to give budget top marks

- Written by Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

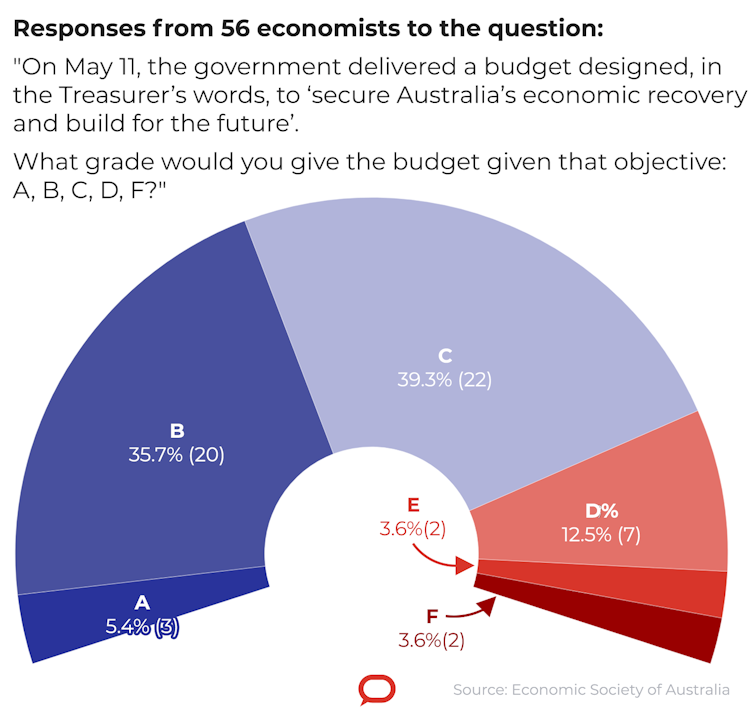

Despite overwhelmingly endorsing the general stance of the 2021 budget, only a few of the 56 leading economists surveyed by the Economic Society of Australia and The Conversation are prepared to give it top marks.

Asked to grade the budget on a scale of A to F given Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s objective of securing Australia’s economic recovery and building for the future[1], only three of the 56 economists surveyed gave it an ‘A’.

But a very large 41% awarded it either an A or a B, up from 37%[2] in last year’s October COVID budget.

The economists chosen to take part in the Economic Society of Australia survey have been recognised by their peers as Australia’s leaders in fields including macroeconomics, economic modelling, housing and budget policy.

Among them are a former head of Australia’s prime minister’s department, a former member of the Reserve Bank board, a former OECD director and two former frontbenchers, one from Labor and one from the Coalition.

Of the panel members who commented on the historic stance of the budget — expanding the size of the deficit beyond what it would have been[3] in order to drive down unemployment — all but three offered enthusiastic endorsement.

Emeritus Professor Sue Richardson of the University of Adelaide commended the government for at last turning its back on a “debt and deficit” mantra, that was “never justified”.

Read more: Exclusive. Top economists back budget push for an unemployment rate beginning with '4'[4]

Professor Richard Holden praised the “watershed”. In due course there should be increased attention paid to the structure and quality of spending, but for now we should applaud the “Frydenberg Pivot”.

Saul Eslake said the strategy of providing further stimulus to push unemployment down to levels not seen consistently since the first half of the 1970s[5] was the right one. It meant the Reserve Bank and the treasury would no longer be working at “cross purposes” as they had been for most of the past two decades.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND[6]

But Eslake said the budget fell short in the A$20 billion it devoted to tax concessions for small business in the mistaken and unfounded belief it is “the engine room of the economy” and in housing measures that failed to heed warnings from history about the risks of ultra-high loan-to-valuation ratios.

Rebecca Cassells of the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre said the claim that 60,000 jobs would flow from extending the temporary loss carry back and full expensing tax concessions was “a stretch,” with the connection quite tenuous.

Bucks, but not the biggest bang

Consultant Nicki Hutley said a bigger boost to the JobSeeker unemployment payment would have achieved much more than the $7.8 billion one-year extension of the “lamington[7]” low and middle income tax offset.

Economic modeller Janine Dixon said while spending more to get more people into work was the “right setting for the times,” Australia had to ensure its workforce was ready to supply the extra aged care and child care and disability services it had funded by delivering the right training, especially in the absence of migration, which has traditionally been used to address workforce shortages.

Labour market specialist Elisabetta Magnani said measures to boost wages in the caring occupations could have achieved the double bonus of drawing more workers into those occupations and shrinking the gender pay gap, given that more than 80% of the workers in residential aged care are female.

Little for net-zero

Michael Keating, a former head of the prime minister’s department, said restoring high wage growth would require big investments in education and training, which sits oddly with the cuts in funding for universities. The extra funding for apprentices and trainees only makes up for past cuts.

Professor Gigi Foster said the $1.7 billion spent on childcare subsidies was only “surface-level fiddling with the sticker price”.

“Where is the supply-side intervention required to make childcare services sustainably accessible and of high quality?” she asked. “Childcare should be viewed as social infrastructure. Instead, when we heard infrastructure, it was mainly code for transportation.”

Read more:

Fewer hard hats, more soft hearts: budget pivots to women and care[8]

Margaret Nowak of Curtin University said a budget that really “built for the future” would not have focused on the “infrastructure of the past”. Professor Richardson lamented that most of the infrastructure spending was on traditional “roads and ports” when the future was net-zero emissions.

“There is little in the budget that supports this transformation,” she said. “It is an extraordinary lost opportunity.

Nicki Hutley said retooling the economy for zero emissions would have brought forth "more jobs, higher wages, more growth and private sector co-investment”.

Some concern about debt

Former OECD director Adrian Blundell-Wignall said a much-greater investment in vaccinations would have helped “get the economy back to work and the borders opened sooner which, in turn, would have saved unemployment benefits, tourism, aviation support and the need for the extension of temporary measures”.

And he was concerned that a jump in US inflation might cause international interest rates to rise faster than expected, forcing Australia to cut its projected budget deficits in order to stabilise net debt.

Read more:

Frydenberg spends the bounty to drive unemployment to new lows[9]

Former International Monetary Fund economist Tony Makin, a critic[10] of government spending during the global financial crisis,

described the budget spending as a “knee-jerk primitive Keynesian reaction” to the COVID recession.

Unease about going into debt to keep and create jobs aside (and very few of the economists surveyed shared Makin’s unease) the criticisms of the economists surveyed relate to execution and details. If Frydenberg had been judged on his approach, most would have given him an A.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND[6]

But Eslake said the budget fell short in the A$20 billion it devoted to tax concessions for small business in the mistaken and unfounded belief it is “the engine room of the economy” and in housing measures that failed to heed warnings from history about the risks of ultra-high loan-to-valuation ratios.

Rebecca Cassells of the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre said the claim that 60,000 jobs would flow from extending the temporary loss carry back and full expensing tax concessions was “a stretch,” with the connection quite tenuous.

Bucks, but not the biggest bang

Consultant Nicki Hutley said a bigger boost to the JobSeeker unemployment payment would have achieved much more than the $7.8 billion one-year extension of the “lamington[7]” low and middle income tax offset.

Economic modeller Janine Dixon said while spending more to get more people into work was the “right setting for the times,” Australia had to ensure its workforce was ready to supply the extra aged care and child care and disability services it had funded by delivering the right training, especially in the absence of migration, which has traditionally been used to address workforce shortages.

Labour market specialist Elisabetta Magnani said measures to boost wages in the caring occupations could have achieved the double bonus of drawing more workers into those occupations and shrinking the gender pay gap, given that more than 80% of the workers in residential aged care are female.

Little for net-zero

Michael Keating, a former head of the prime minister’s department, said restoring high wage growth would require big investments in education and training, which sits oddly with the cuts in funding for universities. The extra funding for apprentices and trainees only makes up for past cuts.

Professor Gigi Foster said the $1.7 billion spent on childcare subsidies was only “surface-level fiddling with the sticker price”.

“Where is the supply-side intervention required to make childcare services sustainably accessible and of high quality?” she asked. “Childcare should be viewed as social infrastructure. Instead, when we heard infrastructure, it was mainly code for transportation.”

Read more:

Fewer hard hats, more soft hearts: budget pivots to women and care[8]

Margaret Nowak of Curtin University said a budget that really “built for the future” would not have focused on the “infrastructure of the past”. Professor Richardson lamented that most of the infrastructure spending was on traditional “roads and ports” when the future was net-zero emissions.

“There is little in the budget that supports this transformation,” she said. “It is an extraordinary lost opportunity.

Nicki Hutley said retooling the economy for zero emissions would have brought forth "more jobs, higher wages, more growth and private sector co-investment”.

Some concern about debt

Former OECD director Adrian Blundell-Wignall said a much-greater investment in vaccinations would have helped “get the economy back to work and the borders opened sooner which, in turn, would have saved unemployment benefits, tourism, aviation support and the need for the extension of temporary measures”.

And he was concerned that a jump in US inflation might cause international interest rates to rise faster than expected, forcing Australia to cut its projected budget deficits in order to stabilise net debt.

Read more:

Frydenberg spends the bounty to drive unemployment to new lows[9]

Former International Monetary Fund economist Tony Makin, a critic[10] of government spending during the global financial crisis,

described the budget spending as a “knee-jerk primitive Keynesian reaction” to the COVID recession.

Unease about going into debt to keep and create jobs aside (and very few of the economists surveyed shared Makin’s unease) the criticisms of the economists surveyed relate to execution and details. If Frydenberg had been judged on his approach, most would have given him an A.

References

- ^ securing Australia’s economic recovery and building for the future (ministers.treasury.gov.au)

- ^ 37% (theconversation.com)

- ^ beyond what it would have been (theconversation.com)

- ^ Exclusive. Top economists back budget push for an unemployment rate beginning with '4' (theconversation.com)

- ^ not seen consistently since the first half of the 1970s (theconversation.com)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ lamington (theconversation.com)

- ^ Fewer hard hats, more soft hearts: budget pivots to women and care (theconversation.com)

- ^ Frydenberg spends the bounty to drive unemployment to new lows (theconversation.com)

- ^ critic (research.treasury.gov.au)

Authors: Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University