Resistance to raising the minimum wage reflects obsolete economic thinking

- Written by Jim Stanford, Economist and Director, Centre for Future Work, Australia Institute; Honorary Professor of Political Economy, University of Sydney

Fewer than 2% of Australian employees[1] work for the minimum wage (now $19.84 an hour). But the federal Fair Work Commission’s annual decision on how much to increase the minimum wage also helps determine pay rises for up to a third[2] of Australian workers.

The adjustment, which comes into effect on July 1[3], flows through to those paid under awards, many on individual contracts and even some enterprise agreements (whose wage increases effectively track the minimum).

Last year’s increase of 1.75%[4] was the smallest in 12 years.

That modest increase, which was delayed several months for most workers, was justified by the dramatic fall-out of the COVID pandemic. But with employment now rebounding – the jobless rate in February was 5.8%, down from its peak of 7.4% in July 2020 – we should expect a stronger “catch-up” increase.

That’s what happened after the Global Financial Crisis, with no change in the minimum wage in 2009, followed by an almost 5% increase in 2010.

But many employer groups are pushing for an outright freeze[5].

The federal government has implicitly sided with them. Its submission[6] to the Fair Work Commission last week warned a higher minimum wage could “dampen employment” and impose a “major constraint” on the post-COVID recovery.

But this argument is based on outdated economic ideas. The evidence from economic research over the past few decades suggests boosting wages back to a normal trajectory would strengthen aggregate demand and consumer confidence, help keep inflation on target, and bolster government revenues at a vital moment in the post-COVID recovery.

Read more: Why kickstarting small business exports could boost stagnant wages[7]

Consistently opposing increases

The Australian Council of Trade Unions has argued for a 3.5% increase[8]. This is well within the normal historical range. It also aligns with the historical view of Reserve Bank of Australia governor Philip Lowe, who in 2018 said[9] annual wage increases of about 3.5% were necessary to meet the bank’s 2.5% inflation target.

It’s not often the union movement and the central bank sing from the same hymn book.

As my colleague Alison Pennington (senior economist with the Centre for Future Work) has written, the Coalition’s position is consistent: it argues against wage increases “whether the economy is weak or strong[10]”.

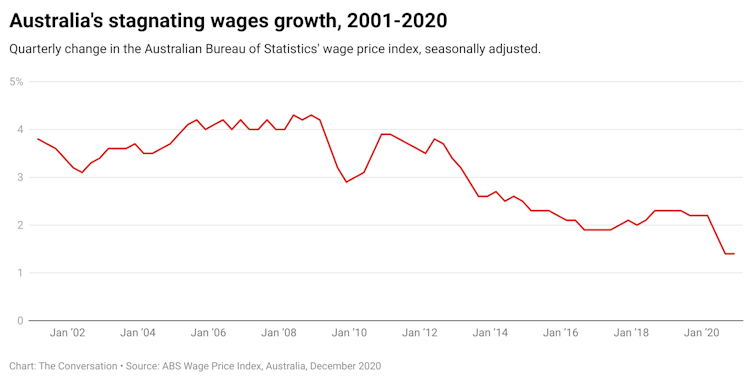

Long before COVID-19, Australia was already experiencing the weakest wage growth since the 1930s. Since end-2013, wage growth has averaged just 2.1% a year[11]. Rosy predictions of an imminent rebound, issued with each federal budget[12], have never come to pass.

CC BY-SA[13] Read more: So much for consensus: Morrison government's industrial relations bill is a business wish list[14] A redundant economic orthodoxy The federal government seems captive to an anachronistic belief that lifting the minimum wages will undermine job creation and competitiveness. This idea has been disproven by important developments in both economic theory and international comparisons. The old economic orthodoxy, typically conveyed via simple supply and demand charts, argued unemployment was inevitable any time governments imposed a minimum wage above the natural “market-clearing equilibrium”. In the past two decades, however, this conventional wisdom has been turned upside down. Starting with groundbreaking US studies[15] of minimum wages and employment in the fast food industry, studies have found higher minimum wages do not generally destroy jobs – and in certain conditions may actually boost employment. Reasons for this include: higher labour force participation and productivity among low-wage workers better job retention and lower turnover, reducing costs of job search and training reducing the “monopsony” power of very large employers to suppress wages more money in workers’ pockets, leading to more consumer spending. Once a leader, now a laggard The Reserve Bank agrees[16] recent minimum wage increases have had no visible negative effect on employment. So the government’s submission to the Fair Work Commission is invoking a discredited shibboleth by suggesting an unavoidable trade-off between wages and employment. It also ignores how much Australia’s minimum wage has been eroded in recent decades. Australia was once a world leader in minimum wage policy. This is no longer true. The best way to measure the labour market impact of the minimum wage is by its “bite” – the ratio of minimum wages to overall labour compensation (best measured by the median wage). Australia’s minimum wage is now 54% of median wages. In 1992 it was 65%. Read more: There's an obvious reason wages aren't growing, but you won't hear it from Treasury or the Reserve Bank[17] That decline has been accompanied by the weakening of other wage-supporting policies (including collective bargaining and awards). It’s no accident Australia has experienced weak wage growth and a falling labour share of GDP, alongside record business profitability[18]. That was the whole idea. The fading ambition of Australia’s minimum wage policy is also evident internationally.

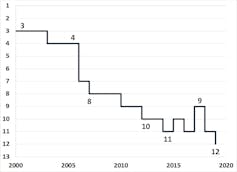

CC BY-SA[13] Read more: So much for consensus: Morrison government's industrial relations bill is a business wish list[14] A redundant economic orthodoxy The federal government seems captive to an anachronistic belief that lifting the minimum wages will undermine job creation and competitiveness. This idea has been disproven by important developments in both economic theory and international comparisons. The old economic orthodoxy, typically conveyed via simple supply and demand charts, argued unemployment was inevitable any time governments imposed a minimum wage above the natural “market-clearing equilibrium”. In the past two decades, however, this conventional wisdom has been turned upside down. Starting with groundbreaking US studies[15] of minimum wages and employment in the fast food industry, studies have found higher minimum wages do not generally destroy jobs – and in certain conditions may actually boost employment. Reasons for this include: higher labour force participation and productivity among low-wage workers better job retention and lower turnover, reducing costs of job search and training reducing the “monopsony” power of very large employers to suppress wages more money in workers’ pockets, leading to more consumer spending. Once a leader, now a laggard The Reserve Bank agrees[16] recent minimum wage increases have had no visible negative effect on employment. So the government’s submission to the Fair Work Commission is invoking a discredited shibboleth by suggesting an unavoidable trade-off between wages and employment. It also ignores how much Australia’s minimum wage has been eroded in recent decades. Australia was once a world leader in minimum wage policy. This is no longer true. The best way to measure the labour market impact of the minimum wage is by its “bite” – the ratio of minimum wages to overall labour compensation (best measured by the median wage). Australia’s minimum wage is now 54% of median wages. In 1992 it was 65%. Read more: There's an obvious reason wages aren't growing, but you won't hear it from Treasury or the Reserve Bank[17] That decline has been accompanied by the weakening of other wage-supporting policies (including collective bargaining and awards). It’s no accident Australia has experienced weak wage growth and a falling labour share of GDP, alongside record business profitability[18]. That was the whole idea. The fading ambition of Australia’s minimum wage policy is also evident internationally.  Australia’s ranking in OECD by minimum wage ‘bite’ Centre for Future Work, from OECD data on minimum wages relative to median wages. In 2002 Australia ranked third among OECD countries according to the minimum wage “bite”. By 2019 we ranked 12th (out of 29 OECD countries with minimum wages). As Australia treads water, other nations are acting on the new economic evidence and lifting minimum wages. In the US, the Biden administration wants to double the federal minimum wage. The argument that lifting Australia’s minimum wage will necessarily cost jobs is outdated and unconvincing. After last year’s very modest increase, a more generous increase will strengthen Australia’s post-COVID recovery, not jeopardise it.

Australia’s ranking in OECD by minimum wage ‘bite’ Centre for Future Work, from OECD data on minimum wages relative to median wages. In 2002 Australia ranked third among OECD countries according to the minimum wage “bite”. By 2019 we ranked 12th (out of 29 OECD countries with minimum wages). As Australia treads water, other nations are acting on the new economic evidence and lifting minimum wages. In the US, the Biden administration wants to double the federal minimum wage. The argument that lifting Australia’s minimum wage will necessarily cost jobs is outdated and unconvincing. After last year’s very modest increase, a more generous increase will strengthen Australia’s post-COVID recovery, not jeopardise it. References

- ^ 2% of Australian employees (www.fwc.gov.au)

- ^ up to a third (d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net)

- ^ on July 1 (www.fwc.gov.au)

- ^ of 1.75% (www.fairwork.gov.au)

- ^ pushing for an outright freeze (www.theaustralian.com.au)

- ^ submission (www.fwc.gov.au)

- ^ Why kickstarting small business exports could boost stagnant wages (theconversation.com)

- ^ a 3.5% increase (www.fwc.gov.au)

- ^ who in 2018 said (rba.gov.au)

- ^ whether the economy is weak or strong (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ 2.1% a year (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ each federal budget (d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ So much for consensus: Morrison government's industrial relations bill is a business wish list (theconversation.com)

- ^ groundbreaking US studies (press.princeton.edu)

- ^ Reserve Bank agrees (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ There's an obvious reason wages aren't growing, but you won't hear it from Treasury or the Reserve Bank (theconversation.com)

- ^ record business profitability (www.abc.net.au)

Authors: Jim Stanford, Economist and Director, Centre for Future Work, Australia Institute; Honorary Professor of Political Economy, University of Sydney