Exhausted by 2020? Here are 5 steps to recover and feel more rested throughout 2021

- Written by Peter A. Heslin, Professor of Management and Scientia Education Fellow, UNSW

For most of us, 2020 was an exhausting year. The COVID-19 pandemic heralded draining physical health concerns, social isolation, job dislocation, uncertainty about the future and related mental health[1] issues.

Although some of us have enjoyed changes such as less commuting, for many the pandemic added extra punch to the main source of stress – engaging in or searching for work.

Here’s what theory and research tells us about how to feel more rested and alive in 2021.

Recovery activity v experience

Recovery is the process of reversing the adverse impacts of stress. Leading recovery researchers Sabine Sonnentag[2] and Charlotte Fritz[3] have highlighted the important distinction between recovery activities (what you do during leisure time) and recovery experiences[4] (what you need to experience during and after those activities to truly recover).

Recovery activities can be passive (such as watching TV, lying on a beach, reading, internet browsing or listening to music) or active (walking, running, playing sport, dancing, swimming, hobbies, spiritual practice, developing a skill, creating something, learning a language and so on).

How well these activities reduce your stress depends on the extent to which they provide you with five types of recovery experiences[5]:

-

psychological detachment: fully disconnecting[6] during non-work time from work-related tasks or even thinking about work issues

-

relaxation: being free of tension and anxiety

-

mastery: challenging situations that provide a sense of progress and achievement (such as being in learning mode[7] to develop a new skill)

-

control: deciding yourself about what to do and when and how to do it

-

enjoyment: the state or process of deriving pleasure from seeing, hearing or doing something.

Of these, psychological detachment is the most potent, according to a 2017 meta-analysis[8] of 54 psychological studies involving more than 26,000 participants.

Benefits of mentally disengaging from work include reduced fatigue and enhanced well-being[9]. On the other hand, inadequate psychological detachment leads to negative thoughts about work[10], exhaustion, physical discomfort[11], and negative emotions both at bedtime[12] and during the next morning[13].

Here are five tips, drawn from the research, to feel more rested and alive.

1. Follow the evidence

There are mixed findings[14] regarding the recovery value of passive, low-effort activities such as watching TV or reading a novel.

More promising are social activities[15], avoiding work-related smartphone use[16] after work, as well as engaging in “receptive” leisure activities[17] (such as attending a concert, game or cultural event) and “creative” leisure activities (designing and making something or expressing yourself in a creative way).

Spending time in “green” environments[18] (parks, bushland, hills) is restorative, particularly when these are natural rather than urban settings. “Blue” environments[19] (the coast, rivers, lakes) are also highly restorative.

Time spent in natural green spaces is more restorative than in urban settings. Shutterstock

Time spent in natural green spaces is more restorative than in urban settings. Shutterstock

Even short lunchtime walks and relaxation exercises[20] lead to feeling more recovered during the afternoon.

Two of the surest ways to recover are to engage in physical exercise and get plenty of quality sleep[21].

2. Assess your ‘boundary management style’

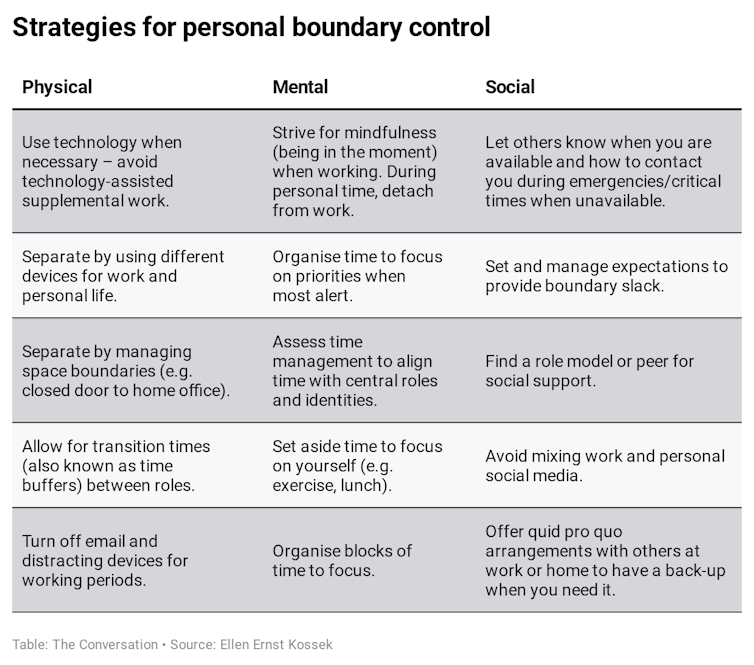

Your boundary management style is the extent to which you integrate or separate your work and life beyond work. Work-life researcher Ellen Kossek has created a survey[22] (it takes about five minutes) to help assess your style and provide suggestions for improvement.

The following table developed by Kossek[23] shows physical, mental and social strategies to manage boundaries and separate your work and life beyond work.

CC BY-SA[24] 3. Cultivate your identity beyond work Many of us define ourselves in terms of our profession[25] (“I’m an engineer”), employer[26] (“I work at …”) and perhaps our performance[27] (“I’m a top performer”). We may also have many other identities[28] related to, for instance, (“I’m a parent”), religion (“I’m a Catholic”), interests (“I’m a guitarist”), activities (“I’m a jogger”) or learning aspirations (“I’m learning Portuguese”). Dan Caprar[29] and Ben Walker[30] suggest two useful ways[31] to prevent being overly invested in work identity. First, reorganise your physical space to reduce visual reminders of your work-related identities (e.g. your laptop, professional books, performance awards) and replace them with reminders of your other identities. Second, do some “identity work” and “identity play[32]”, reflecting on the identities you cherish and experimenting with potential new identities. Read more: Here's why you're checking work emails on holidays (and how to stop)[33] 4. Make time for better recovery experiences Document what you do when not working. Ask yourself how much these activities enable you to truly experience psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, control and enjoyment. Then experiment with alternative activities that might provide richer recovery experiences. This will typically require less time on things such as news media[34] (especially pandemic updates[35] and doomscrolling[36]), TV, social media[37], online shopping[38] or video games[39], gambling[40], pornography[41], alcohol[42] or illicit drugs[43] to recover.

CC BY-SA[24] 3. Cultivate your identity beyond work Many of us define ourselves in terms of our profession[25] (“I’m an engineer”), employer[26] (“I work at …”) and perhaps our performance[27] (“I’m a top performer”). We may also have many other identities[28] related to, for instance, (“I’m a parent”), religion (“I’m a Catholic”), interests (“I’m a guitarist”), activities (“I’m a jogger”) or learning aspirations (“I’m learning Portuguese”). Dan Caprar[29] and Ben Walker[30] suggest two useful ways[31] to prevent being overly invested in work identity. First, reorganise your physical space to reduce visual reminders of your work-related identities (e.g. your laptop, professional books, performance awards) and replace them with reminders of your other identities. Second, do some “identity work” and “identity play[32]”, reflecting on the identities you cherish and experimenting with potential new identities. Read more: Here's why you're checking work emails on holidays (and how to stop)[33] 4. Make time for better recovery experiences Document what you do when not working. Ask yourself how much these activities enable you to truly experience psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, control and enjoyment. Then experiment with alternative activities that might provide richer recovery experiences. This will typically require less time on things such as news media[34] (especially pandemic updates[35] and doomscrolling[36]), TV, social media[37], online shopping[38] or video games[39], gambling[40], pornography[41], alcohol[42] or illicit drugs[43] to recover.  Passive leisure activities are less likely to provide the five key recovery experiences of psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, control and enjoyment. Shutterstock You will make it easier to give up activities with minimal recovery value if you supplant them with more rejuvenating alternatives you enjoy[44]. Read more: Three ways to achieve your New Year’s resolutions by building 'goal infrastructure'[45] 5. Form new habits Habits are behaviours we automatically repeat[46] in certain situations. Often we fail to develop better habits by being too ambitious. The “tiny habits[47]” approach suggests thinking smaller, with “ABC recipes” that identify: anchor moments, when you will enact your intended behaviour behaviours you will undertake during those moments celebration to create a positive feeling that helps this behaviour become a habit. Examples of applying this approach are: After I eat lunch, I will walk for at least ten minutes (ideally somewhere green). I will celebrate by enjoying what I see along the way. After I finish work, I will engage in 45 minutes of exercise before dinner. I will celebrate by raising my arms in a V shape and saying “Victory!” After 8.30pm I will not look at email or think about work. I will celebrate by reminding myself I deserve to switch off. Perhaps the most essential ingredient for building better recovery habits is to steer away from feeling burdened by ideas about what you “should” do to recover. Enjoy the process of experimenting with different recovery activities that, given all your work and life commitments, seem most promising, viable and fun.

Passive leisure activities are less likely to provide the five key recovery experiences of psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, control and enjoyment. Shutterstock You will make it easier to give up activities with minimal recovery value if you supplant them with more rejuvenating alternatives you enjoy[44]. Read more: Three ways to achieve your New Year’s resolutions by building 'goal infrastructure'[45] 5. Form new habits Habits are behaviours we automatically repeat[46] in certain situations. Often we fail to develop better habits by being too ambitious. The “tiny habits[47]” approach suggests thinking smaller, with “ABC recipes” that identify: anchor moments, when you will enact your intended behaviour behaviours you will undertake during those moments celebration to create a positive feeling that helps this behaviour become a habit. Examples of applying this approach are: After I eat lunch, I will walk for at least ten minutes (ideally somewhere green). I will celebrate by enjoying what I see along the way. After I finish work, I will engage in 45 minutes of exercise before dinner. I will celebrate by raising my arms in a V shape and saying “Victory!” After 8.30pm I will not look at email or think about work. I will celebrate by reminding myself I deserve to switch off. Perhaps the most essential ingredient for building better recovery habits is to steer away from feeling burdened by ideas about what you “should” do to recover. Enjoy the process of experimenting with different recovery activities that, given all your work and life commitments, seem most promising, viable and fun. References

- ^ mental health (www.blackdoginstitute.org.au)

- ^ Sabine Sonnentag (www.uni-mannheim.de)

- ^ Charlotte Fritz (www.fritzpoplab.com)

- ^ recovery experiences (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ recovery experiences (doi.apa.org)

- ^ fully disconnecting (doi.org)

- ^ in learning mode (doi.org)

- ^ 2017 meta-analysis (doi.org)

- ^ reduced fatigue and enhanced well-being (doi.org)

- ^ negative thoughts about work (doi.org)

- ^ exhaustion, physical discomfort (doi.org)

- ^ at bedtime (doi.org)

- ^ during the next morning (doi.org)

- ^ mixed findings (doi.org)

- ^ social activities (doi.org)

- ^ work-related smartphone use (doi.org)

- ^ “receptive” leisure activities (dx.doi.org)

- ^ “green” environments (doi.org)

- ^ “Blue” environments (doi.org)

- ^ walks and relaxation exercises (doi.org)

- ^ physical exercise and get plenty of quality sleep (doi.org)

- ^ a survey (purdue.qualtrics.com)

- ^ developed by Kossek (core.ac.uk)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ profession (doi.org)

- ^ employer (doi.org)

- ^ performance (doi.org)

- ^ other identities (doi.org)

- ^ Dan Caprar (www.sydney.edu.au)

- ^ Ben Walker (people.wgtn.ac.nz)

- ^ two useful ways (theconversation.com)

- ^ identity play (doi.org)

- ^ Here's why you're checking work emails on holidays (and how to stop) (theconversation.com)

- ^ news media (doi.org)

- ^ pandemic updates (doi.org)

- ^ doomscrolling (www.wired.com)

- ^ social media (doi.org)

- ^ online shopping (doi.org)

- ^ video games (doi.org)

- ^ gambling (doi.org)

- ^ pornography (doi.org)

- ^ alcohol (doi.org)

- ^ illicit drugs (doi.org)

- ^ alternatives you enjoy (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ Three ways to achieve your New Year’s resolutions by building 'goal infrastructure' (theconversation.com)

- ^ automatically repeat (doi.org)

- ^ tiny habits (www.tinyhabits.com)

Authors: Peter A. Heslin, Professor of Management and Scientia Education Fellow, UNSW