How could they not have known? (And how can we be sure they will in future?)

- Written by Andrew Hopkins, Emeritus Professor of Sociology, Australian National University

How could they not have known?

That was the question on everyone’s lips after leaders of the Australian defence force claimed not to have known[1] about the atrocities committed by special forces in Afghanistan.

It is now being asked about the leadership of Rio Tinto after that company ignored the wishes of the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura peoples and destroyed[2] caves containing priceless Aboriginal heritage dating back 46,000 years.

Three of Rio’s most senior executives, including the chief executive, apparently knew nothing about what was happening until it was too late. This was:

-

despite a detailed archaeological report about the heritage value of the caves which the company had commissioned

-

despite representations of traditional landowners about the significance of the caves, and that they be preserved

-

despite the concerns of Rio’s own cultural heritage staff in Western Australia

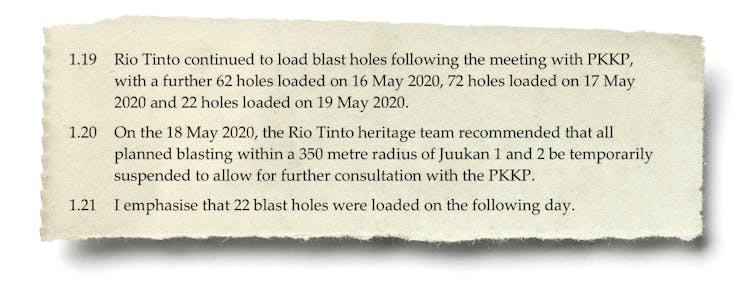

Extract from Joint Standing Committee on Northern Australia's interim report[3] How could they not have known? The parliament’s joint standing committee inquiry into the destruction of the Juukan Gorge caves is a golden opportunity to get an answer. Unfortunately, this month’s interim report[4] only touches on this question, and none of the eight recommendations it addresses to Rio Tinto deal with it. The closest it comes is an observation that Rio had a structure which sidelined heritage protection within the organisation, lack of senior management oversight, and no clear channel of communication to enable the escalation of heritage concerns to executives based in London Coalition committee member Dean Smith, Senator for Western Australia, went further in additional comments appended to the report it is my view that … board members … enabled a culture to develop at Rio Tinto where non-executive level management did not feel empowered to inform the executive of the significance of the rock shelters The problem is that bad news about what is happening at lower levels of large organisations travels up slowly, if at all. Matters get “stuck”, and are not addressed. Bad news doesn’t travel up Paedophile priests, money laundering by banks, fraudulent misrepresentation by auto companies, corruption in police departments, unacceptable safety risks taken by mining companies – in each case when these sort of issues come to light, those at the top say they knew nothing about it. There are reasons for this failure to know: the people at the top would rather not hear about it, and so those below avoid telling them; whistleblowers get ostracised; people ‘"in the know" remain silent out of self-interest or misplaced loyalty; bonuses encourage a focus on profit at the expense of all else. Read more: Juukan Gorge inquiry puts Rio Tinto on notice, but without drastic reforms, it could happen again[5] So what should leaders do to change things? The first thing is to acknowledge that there is likely to be bad news – problems, challenges and things that are not right. Indeed, if they are not hearing bad news, something is wrong. Chief executives and board members need to develop a sense of “chronic unease” about whether they are really getting the full story from their subordinates or whether there are hidden time bombs ticking away that will eventually explode. They need to personally seek out and reward the bearers of bad news. Bad news needs to be sought out Second, they need to structure their organisation to maximise the chance of bad news reaching the top. What is required in large commercial organisations like Rio Tinto is someone on the executive committee whose job is ensuring non-commercial environmental, social and governance risks are managed. That executive should neither be responsible for, nor rewarded for, any aspect of commercial performance and should be given a direct line to board members. Read more: Corporate dysfunction on Indigenous affairs: Why heads rolled at Rio Tinto[6] Specialist staff reporting to that executive need to be embedded at lower levels of the organisation and in each of the company’s divisions. The interim report concludes that Rio Tinto’s board review[7] has not fully grappled with these issues. Yet Rio Tinto has made some positive changes following the catastrophe. First, it has acknowledged that its cultural heritage staff in Western Australia have had no reporting line to higher-level social performance staff. Indeed, there have been no higher-level staff exclusively responsible for impacts to communities. Rio is making an (uneven) start The company is creating a “social performance” function, reporting to a group executive on the corporate executive committee. Second (and of concern) Rio Tinto has specified that this executive will also be the culmination point for reports on new mining “projects”. Projects[8] are commercially and engineering oriented and might come to be seen as more important to the company and requiring greater focus from the group executive than health, safety, environment and social concerns. Read more: Rio Tinto just blasted away an ancient Aboriginal site. Here’s why that was allowed[9] Third, social performance staff will be “embedded” within local mine management and product groups. The critical question is whether reports from these social performance specialists will get diluted by the time they reach the top. The best chance is a direct line to a specialist in corporate headquarters who reports to a “group executive social performance” on the executive committee. Rio Tinto has appointed a chief adviser Indigenous affairs who will report to the chief executive, although it is unclear what authority the position will hold. The announced changes leave much uncertain. The inquiry will hold further hearings next year[10]. It will get the chance to insist on proper structures.

Extract from Joint Standing Committee on Northern Australia's interim report[3] How could they not have known? The parliament’s joint standing committee inquiry into the destruction of the Juukan Gorge caves is a golden opportunity to get an answer. Unfortunately, this month’s interim report[4] only touches on this question, and none of the eight recommendations it addresses to Rio Tinto deal with it. The closest it comes is an observation that Rio had a structure which sidelined heritage protection within the organisation, lack of senior management oversight, and no clear channel of communication to enable the escalation of heritage concerns to executives based in London Coalition committee member Dean Smith, Senator for Western Australia, went further in additional comments appended to the report it is my view that … board members … enabled a culture to develop at Rio Tinto where non-executive level management did not feel empowered to inform the executive of the significance of the rock shelters The problem is that bad news about what is happening at lower levels of large organisations travels up slowly, if at all. Matters get “stuck”, and are not addressed. Bad news doesn’t travel up Paedophile priests, money laundering by banks, fraudulent misrepresentation by auto companies, corruption in police departments, unacceptable safety risks taken by mining companies – in each case when these sort of issues come to light, those at the top say they knew nothing about it. There are reasons for this failure to know: the people at the top would rather not hear about it, and so those below avoid telling them; whistleblowers get ostracised; people ‘"in the know" remain silent out of self-interest or misplaced loyalty; bonuses encourage a focus on profit at the expense of all else. Read more: Juukan Gorge inquiry puts Rio Tinto on notice, but without drastic reforms, it could happen again[5] So what should leaders do to change things? The first thing is to acknowledge that there is likely to be bad news – problems, challenges and things that are not right. Indeed, if they are not hearing bad news, something is wrong. Chief executives and board members need to develop a sense of “chronic unease” about whether they are really getting the full story from their subordinates or whether there are hidden time bombs ticking away that will eventually explode. They need to personally seek out and reward the bearers of bad news. Bad news needs to be sought out Second, they need to structure their organisation to maximise the chance of bad news reaching the top. What is required in large commercial organisations like Rio Tinto is someone on the executive committee whose job is ensuring non-commercial environmental, social and governance risks are managed. That executive should neither be responsible for, nor rewarded for, any aspect of commercial performance and should be given a direct line to board members. Read more: Corporate dysfunction on Indigenous affairs: Why heads rolled at Rio Tinto[6] Specialist staff reporting to that executive need to be embedded at lower levels of the organisation and in each of the company’s divisions. The interim report concludes that Rio Tinto’s board review[7] has not fully grappled with these issues. Yet Rio Tinto has made some positive changes following the catastrophe. First, it has acknowledged that its cultural heritage staff in Western Australia have had no reporting line to higher-level social performance staff. Indeed, there have been no higher-level staff exclusively responsible for impacts to communities. Rio is making an (uneven) start The company is creating a “social performance” function, reporting to a group executive on the corporate executive committee. Second (and of concern) Rio Tinto has specified that this executive will also be the culmination point for reports on new mining “projects”. Projects[8] are commercially and engineering oriented and might come to be seen as more important to the company and requiring greater focus from the group executive than health, safety, environment and social concerns. Read more: Rio Tinto just blasted away an ancient Aboriginal site. Here’s why that was allowed[9] Third, social performance staff will be “embedded” within local mine management and product groups. The critical question is whether reports from these social performance specialists will get diluted by the time they reach the top. The best chance is a direct line to a specialist in corporate headquarters who reports to a “group executive social performance” on the executive committee. Rio Tinto has appointed a chief adviser Indigenous affairs who will report to the chief executive, although it is unclear what authority the position will hold. The announced changes leave much uncertain. The inquiry will hold further hearings next year[10]. It will get the chance to insist on proper structures. References

- ^ not to have known (theconversation.com)

- ^ destroyed (www.youtube.com)

- ^ Extract from Joint Standing Committee on Northern Australia's interim report (www.aph.gov.au)

- ^ interim report (www.aph.gov.au)

- ^ Juukan Gorge inquiry puts Rio Tinto on notice, but without drastic reforms, it could happen again (theconversation.com)

- ^ Corporate dysfunction on Indigenous affairs: Why heads rolled at Rio Tinto (theconversation.com)

- ^ board review (www.riotinto.com)

- ^ Projects (www.riotinto.com)

- ^ Rio Tinto just blasted away an ancient Aboriginal site. Here’s why that was allowed (theconversation.com)

- ^ next year (www.aph.gov.au)

Authors: Andrew Hopkins, Emeritus Professor of Sociology, Australian National University