What the finance industry can tell us about what's holding back wages

- Written by Robert Sobyra, PhD Candidate, The University of Queensland

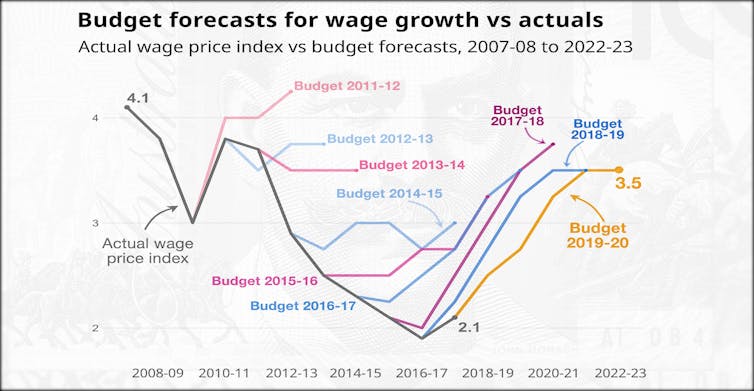

Wage growth has fallen short of the official forecasts for an extraordinary eight consecutive budgets.

Commonwealth budget papers, ABS wage price index

[1]

Commonwealth budget papers, ABS wage price index

[1]

When asked what’s needed to actually get wage growth up in line with the repeated forecasts, prime minister Scott Morrison usually mentions productivity, and he is usually optimistic. He says the more that is produced per worker, the more can be paid per worker[2].

I believe that once you see that sustained productivity and that sustained profit, then that should flow through to wages.

It was the line pushed by Business Council chief executive Jennifer Westacott[3] on budget night:

We have been calling for wage increases for ages. The question is how you get them. You get them through the economy doing more, you get them through productivity going up. I mean, the link between productivity and wage increases is not theoretical, it’s factual.

But not in the case of the finance industry.

And what has happened in that industry helps tell a larger story.

Although the finance industry has made enormous productivity gains in recent decades, and although workers could have been given a share of the gains, they hardly have. This suggests that while productivity gains are a necessary condition for sustained real wage growth, they are not a sufficient condition.

What productivity is

Productivity is the amount of output produced per given unit of input, usually labour. The theory says that if firms can find ways to produce more with less, for example by investing in technology, software and research and development, then the gains from the extra that’s produced will be shared between the firm’s owners and its workers in the form of higher profits and higher wages. They’ll all win.

This path from productivity growth to wage growth is often presented as inevitable, and for much of the 20th Century, it seemed to be. It became an article of faith, crystallised nicely by Dr Stephen Kirchner just ahead of the budget[4]: “Raising productivity growth is still the best way to improve average workers’ incomes.”

But history has a habit of shattering truisms.

The story of Australia’s finance industry over the last 40 years is a case study.

Finance: lots of take, little give

In the heat of the battle over the banking royal commission in 2017 the then treasurer Scott Morrison painted the finance sector[5] as “key to jobs and growth”. It underpinned “everything that happens in our economy.”

He wasn’t wrong. Over the last four decades, finance has become the single biggest driver of economic activity in Australia, doubling its contribution to gross domestic product since 1975. Of the 19 major industries tracked by the Bureau of Statistics, “Financial and Insurance Services” contributes 8.8% to GDP[6], compared to 7.8% from Construction, 7.6% from Mining, and 7.0% from Healthcare and Social Assistance.

In conventional economic terms, it is an industry that has done everything right.

As it has grown in importance to the economy, it has consistently lifted its productivity. Its output per hour worked has more than doubled during a quarter century in which the economy as a whole has grown 50%.

Read more: The workplace challenge facing Australia (spoiler alert – it’s not technology)[7]

The gains have been due to consistent investments in technology and research and development. As it has poured money into tech, it wound down its investments in buildings. This accords with what we can see. Banks have moved away from “bricks and mortar” services toward digital and virtual services.

So far, so good. This is precisely what the textbook says industries should be doing.

Yet there’s a problem: these big productivity improvements haven’t produced the outcomes the theory predicts. Wages haven’t been growing in line with productivity.

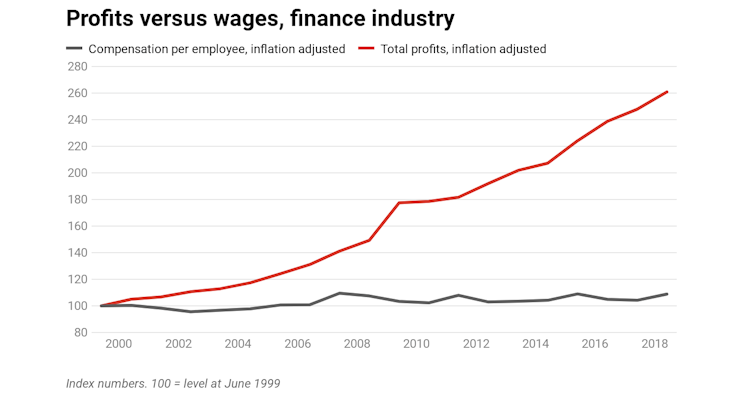

The vast majority of the productivity dividend in finance has been reaped in profits rather than wages. In other words, almost all the gains have gone to the owners and shareholders of the businesses, rather than their workers.

Another way of looking at it is through the eyes of the average employee in the industry. When we take into account the rising cost of living (inflation), the average finance worker has experienced no growth in wages since the turn of this century, almost two decades ago. The inflation-adjusted profits of businesses that employ them have boomed.

ABS Australian National Accounts[8]

What gives?

Anwar Shaikh is one of the world’s leading economists and a professor at The New School in New York City. He’s what we call a “classical” economist. That means he’s more interested in describing the economy that exists than idealising it in neat theories that can be expressed in mathematical equations but bear little resemblance to what happens.

His latest book[9], which deserves a Nobel Prize, had something important to say about this apparent decoupling of productivity and wages – a pattern that has emerged across many OECD countries[10].

He argues that productivity provides the foundation for real wage increases, but that those increases are not automatic. His proposition is simple to the point of common sense: wages respond to productivity growth depending on the strength of workers bargaining power relative to that of their employers. Less bargaining power makes it less likely wages will grow in step with productivity.

Read more:

Ultra low wage growth isn't accidental. It is the intended outcome of government policies[11]

The bottom line is that productivity growth alone will not deliver the goods for workers unless the right social, political and institutional conditions are in place to translate it into wage growth.

The conditions that delivered this linkage for much of the 20th Century were not natural or automatic; they were hard-won and they have been steadily eroded[12] since the 1980s.

Bringing back old-school unionisation need not be the only answer. Some of today’s unions are combative and fiercely protective of old ways of working, not necessarily what’s needed for a competitive economy. Equally though, restoring the productivity-wages link is probably going to take a little more than the Reserve Bank Governor begging companies[13] to pay their workers more.

One alternative comes from Singapore, consistently ranked among the most competitive nations in the world (currently second[14] to the United States). Singapore has a long tradition of actively managing the link between wage increases and productivity growth (of course, it also has a reputation for actively managing other things, which mightn’t always be the best).

In effect, the Singapore model pegs wages to economic performance, especially productivity. The primary mechanism is a tripartite institution of government, industry and unions, known as the National Wages Council[15]. Its job is to set non-mandatory wage guidelines. The system isn’t binding, but is built on consensus and flexibility. It’s been mightily effective.

It is naïve to suggest that we could import entire policies from Singapore, Sweden or anywhere else. Nevertheless there are lessons from these systems we could explore. Whoever forms government in five weeks time might need them.

ABS Australian National Accounts[8]

What gives?

Anwar Shaikh is one of the world’s leading economists and a professor at The New School in New York City. He’s what we call a “classical” economist. That means he’s more interested in describing the economy that exists than idealising it in neat theories that can be expressed in mathematical equations but bear little resemblance to what happens.

His latest book[9], which deserves a Nobel Prize, had something important to say about this apparent decoupling of productivity and wages – a pattern that has emerged across many OECD countries[10].

He argues that productivity provides the foundation for real wage increases, but that those increases are not automatic. His proposition is simple to the point of common sense: wages respond to productivity growth depending on the strength of workers bargaining power relative to that of their employers. Less bargaining power makes it less likely wages will grow in step with productivity.

Read more:

Ultra low wage growth isn't accidental. It is the intended outcome of government policies[11]

The bottom line is that productivity growth alone will not deliver the goods for workers unless the right social, political and institutional conditions are in place to translate it into wage growth.

The conditions that delivered this linkage for much of the 20th Century were not natural or automatic; they were hard-won and they have been steadily eroded[12] since the 1980s.

Bringing back old-school unionisation need not be the only answer. Some of today’s unions are combative and fiercely protective of old ways of working, not necessarily what’s needed for a competitive economy. Equally though, restoring the productivity-wages link is probably going to take a little more than the Reserve Bank Governor begging companies[13] to pay their workers more.

One alternative comes from Singapore, consistently ranked among the most competitive nations in the world (currently second[14] to the United States). Singapore has a long tradition of actively managing the link between wage increases and productivity growth (of course, it also has a reputation for actively managing other things, which mightn’t always be the best).

In effect, the Singapore model pegs wages to economic performance, especially productivity. The primary mechanism is a tripartite institution of government, industry and unions, known as the National Wages Council[15]. Its job is to set non-mandatory wage guidelines. The system isn’t binding, but is built on consensus and flexibility. It’s been mightily effective.

It is naïve to suggest that we could import entire policies from Singapore, Sweden or anywhere else. Nevertheless there are lessons from these systems we could explore. Whoever forms government in five weeks time might need them.

References

- ^ Commonwealth budget papers, ABS wage price index (budget.gov.au)

- ^ the more can be paid per worker (sjm.ministers.treasury.gov.au)

- ^ Jennifer Westacott (www.bca.com.au)

- ^ just ahead of the budget (www.ussc.edu.au)

- ^ painted the finance sector (www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au)

- ^ contributes 8.8% to GDP (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ The workplace challenge facing Australia (spoiler alert – it’s not technology) (theconversation.com)

- ^ ABS Australian National Accounts (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ latest book (global.oup.com)

- ^ across many OECD countries (www.oecd-ilibrary.org)

- ^ Ultra low wage growth isn't accidental. It is the intended outcome of government policies (theconversation.com)

- ^ steadily eroded (www.oecd.org)

- ^ begging companies (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ second (reports.weforum.org)

- ^ National Wages Council (books.google.com.au)

Authors: Robert Sobyra, PhD Candidate, The University of Queensland