Potentially unaffordable, and it still won't fix bracket creep. The Coalition's $300 billion tax plan assessed

- Written by Danielle Wood, Program Director, Budget Policy and Institutional Reform, Grattan Institute

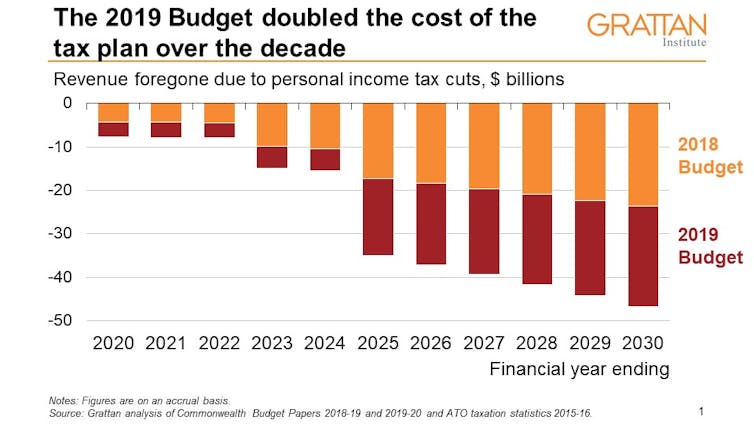

The big surprise in last week’s budget was the size of new income tax cuts – A$158 billion[1] over a decade, in addition to the A$144 billion already promised[2] in last year’s budget.

A lot of the plan doesn’t take effect until 2024-25, so it’s easy to dismiss[3] as tax cuts on the never-never. But given it’s a central plank of the government’s campaign for re-election, it deserves closer scrutiny.

Grattan Institute[4]

The plan comes in three stages.

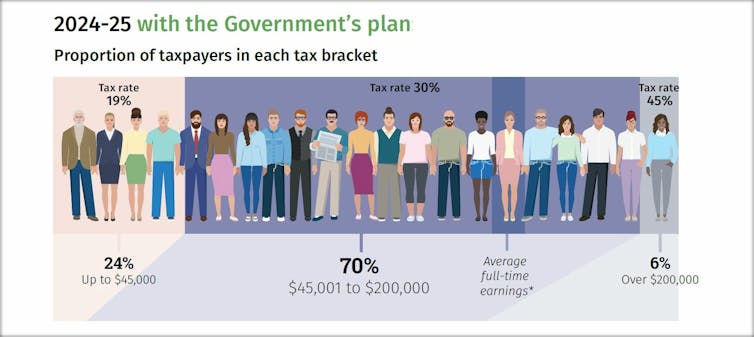

The major part of stage 1 is the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset – giving everyone earning less than $126,000 a cheque in the mail come July and then for the following three years. Stage 2 (2022-23) would lift the top threshold of the 19% and the 32.5% brackets. The biggest cuts would come in stage 3 (2024-25) when the government removed the 37% bracket and cut the 32.5% rate to 30%.

Everyone earning between $45,000 and $200,000 would face the same 30% marginal tax rate.

Grattan Institute[4]

The plan comes in three stages.

The major part of stage 1 is the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset – giving everyone earning less than $126,000 a cheque in the mail come July and then for the following three years. Stage 2 (2022-23) would lift the top threshold of the 19% and the 32.5% brackets. The biggest cuts would come in stage 3 (2024-25) when the government removed the 37% bracket and cut the 32.5% rate to 30%.

Everyone earning between $45,000 and $200,000 would face the same 30% marginal tax rate.

2019 Budget infographic[5]

Unsurprisingly, in absolute terms the biggest beneficiaries would be high-income earners. More than half the benefit would go to the top 20% of earners, those with taxable income over $87,500 a year.

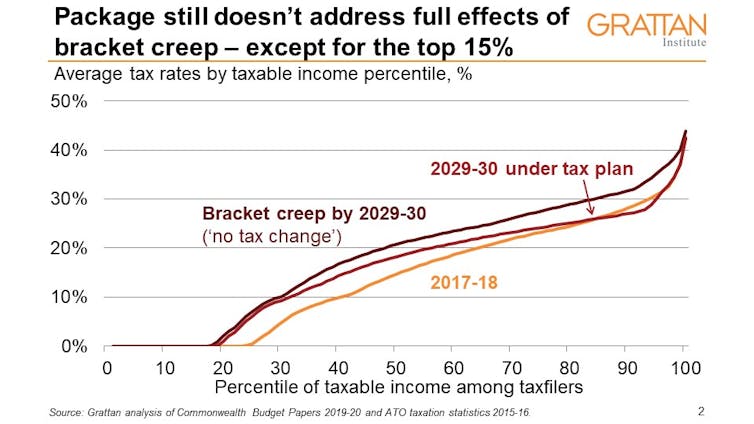

But to better understand what the plan would do to the progressivity of the system, we need to consider what would happen to rates without the plan.

Without change, the average tax rate would increase across the income distribution, as wage growth pushed people into higher tax brackets[6].

The plan would prevent some of that bracket creep by lowering future tax rates.

Most taxpayers would be better-off than without a change – but high-income earners would benefit the most.

Read more:

NATSEM: federal budget will widen gap between rich and poor[7]

It goes part-way to addressing bracket creep for low and middle income earners. Someone in the middle of the income distribution would pay 3.6% more tax in 2029-30 than today, instead of 6.1% more without the plan.

But Australia’s highest earners – the top 15% of taxpayers – would escape bracket creep entirely, paying the same average tax rate or less in 2029-30 than today.

2019 Budget infographic[5]

Unsurprisingly, in absolute terms the biggest beneficiaries would be high-income earners. More than half the benefit would go to the top 20% of earners, those with taxable income over $87,500 a year.

But to better understand what the plan would do to the progressivity of the system, we need to consider what would happen to rates without the plan.

Without change, the average tax rate would increase across the income distribution, as wage growth pushed people into higher tax brackets[6].

The plan would prevent some of that bracket creep by lowering future tax rates.

Most taxpayers would be better-off than without a change – but high-income earners would benefit the most.

Read more:

NATSEM: federal budget will widen gap between rich and poor[7]

It goes part-way to addressing bracket creep for low and middle income earners. Someone in the middle of the income distribution would pay 3.6% more tax in 2029-30 than today, instead of 6.1% more without the plan.

But Australia’s highest earners – the top 15% of taxpayers – would escape bracket creep entirely, paying the same average tax rate or less in 2029-30 than today.

Grattan Institute[8]

This result would be a shift in the proportion of tax paid at different points in the income distribution.

Middle earners, those earning between the third to top and the third to bottom ten percents of the income distribution, would pay a larger share of tax in 2029-30 than they do today: 23% compared to 20%.

But high-income earners, those in the top fifth of the income distribution, would pay a smaller share of tax: 65% in 2029-30 compared to 68% today.

It’s more a tax cut than tax reform

The government has been keen to sell the tax package as a “huge reform[9]” because it removes an entire tax bracket.

It says flattening the tax scale would create a greater incentive for higher-income earners to work. But unlike earlier tax reform packages, there has been little in the way of clear articulation or modelling to demonstrate that this would be the case. And there are reasons to doubt that it would be the case.

Read more:

Mothers have little to show for extra days of work under new tax changes[10]

The people who would benefit most from the tax reform would be in the top 6% of the income distribution in 2024-25. Barring major changes to gender work patterns in the next five years, they would be disproportionately men, working full time. But as the Henry Tax Review[11] pointed out, the people who are the most responsive to changes in effective tax rates are second-earners (mainly women) working part-time.

Proper reform of the income tax system would lower the economic barriers to second-earners working more: the increase in tax, the cuts in family and childcare benefits and higher childcare costs that accompany working more.

And it might not be affordable

The budget numbers point to a decade of surpluses, exceeding 1% of GDP by 2026-27, even with the tax cuts. But the surpluses rely on payments as a share of gross domestic product falling steadily over the decade, from 24.9% of GDP today to 23.6% by 2029-30[12].

Achieving such a reduction would require significant cuts in spending growth across almost every major spending area, during a period when we know that an ageing population will increase spending pressures, particularly on health and welfare. The Parliamentary Budget Office[13] says ageing will add 0.3% of GDP a year to spending by 2028-29.

The approach marks a change since the 2016-17 budget, when the government forecast that payments would grow as a share of GDP over the decade because of the ageing population. There have not been enough significant savings measures in the past three budgets to explain the turnaround. It appears to be more driven by assumption than by reality.

Read more:

Expect a budget that breaks the intergenerational bargain, like the one before it, and before that[14]

If we were to make the still-conservative assumption that spending remained merely constant as a share of GDP at 24.9%, the third stage of the tax cuts would push the budget back into deficit in 2024-25.

The bottom line

The pre-election tax package finally does something about bracket creep – but solves it only for the highest of earners.

It passes up the opportunity for more comprehensive reform. And most disconcertingly, it punches a sizeable hole in government revenue just at the time an ageing population will start to demand that more money be spent.

Read more:

What will the Coalition be remembered for on tax? Tinkering, blunders and lost opportunities[15]

Grattan Institute[8]

This result would be a shift in the proportion of tax paid at different points in the income distribution.

Middle earners, those earning between the third to top and the third to bottom ten percents of the income distribution, would pay a larger share of tax in 2029-30 than they do today: 23% compared to 20%.

But high-income earners, those in the top fifth of the income distribution, would pay a smaller share of tax: 65% in 2029-30 compared to 68% today.

It’s more a tax cut than tax reform

The government has been keen to sell the tax package as a “huge reform[9]” because it removes an entire tax bracket.

It says flattening the tax scale would create a greater incentive for higher-income earners to work. But unlike earlier tax reform packages, there has been little in the way of clear articulation or modelling to demonstrate that this would be the case. And there are reasons to doubt that it would be the case.

Read more:

Mothers have little to show for extra days of work under new tax changes[10]

The people who would benefit most from the tax reform would be in the top 6% of the income distribution in 2024-25. Barring major changes to gender work patterns in the next five years, they would be disproportionately men, working full time. But as the Henry Tax Review[11] pointed out, the people who are the most responsive to changes in effective tax rates are second-earners (mainly women) working part-time.

Proper reform of the income tax system would lower the economic barriers to second-earners working more: the increase in tax, the cuts in family and childcare benefits and higher childcare costs that accompany working more.

And it might not be affordable

The budget numbers point to a decade of surpluses, exceeding 1% of GDP by 2026-27, even with the tax cuts. But the surpluses rely on payments as a share of gross domestic product falling steadily over the decade, from 24.9% of GDP today to 23.6% by 2029-30[12].

Achieving such a reduction would require significant cuts in spending growth across almost every major spending area, during a period when we know that an ageing population will increase spending pressures, particularly on health and welfare. The Parliamentary Budget Office[13] says ageing will add 0.3% of GDP a year to spending by 2028-29.

The approach marks a change since the 2016-17 budget, when the government forecast that payments would grow as a share of GDP over the decade because of the ageing population. There have not been enough significant savings measures in the past three budgets to explain the turnaround. It appears to be more driven by assumption than by reality.

Read more:

Expect a budget that breaks the intergenerational bargain, like the one before it, and before that[14]

If we were to make the still-conservative assumption that spending remained merely constant as a share of GDP at 24.9%, the third stage of the tax cuts would push the budget back into deficit in 2024-25.

The bottom line

The pre-election tax package finally does something about bracket creep – but solves it only for the highest of earners.

It passes up the opportunity for more comprehensive reform. And most disconcertingly, it punches a sizeable hole in government revenue just at the time an ageing population will start to demand that more money be spent.

Read more:

What will the Coalition be remembered for on tax? Tinkering, blunders and lost opportunities[15]

References

- ^ A$158 billion (www.budget.gov.au)

- ^ A$144 billion already promised (static.treasury.gov.au)

- ^ easy to dismiss (theconversation.com)

- ^ Grattan Institute (grattan.edu.au)

- ^ 2019 Budget infographic (budget.gov.au)

- ^ into higher tax brackets (theconversation.com)

- ^ NATSEM: federal budget will widen gap between rich and poor (theconversation.com)

- ^ Grattan Institute (grattan.edu.au)

- ^ huge reform (www.afr.com)

- ^ Mothers have little to show for extra days of work under new tax changes (theconversation.com)

- ^ Henry Tax Review (taxreview.treasury.gov.au)

- ^ 23.6% by 2029-30 (www.budget.gov.au)

- ^ Parliamentary Budget Office (www.aph.gov.au)

- ^ Expect a budget that breaks the intergenerational bargain, like the one before it, and before that (theconversation.com)

- ^ What will the Coalition be remembered for on tax? Tinkering, blunders and lost opportunities (theconversation.com)

Authors: Danielle Wood, Program Director, Budget Policy and Institutional Reform, Grattan Institute