Bad news. Closing coal-fired power stations costs jobs. We need to prepare

- Written by Paul Burke, Associate Professor, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

Australia’s electricity sector has begun to transition away from coal, with coal’s contribution to our electricity mix falling from around four-fifths 13 years ago to around three-fifths today.

Twelve coal-fired power stations closed between 2012 and 2017.

There are clear upsides to the transition, among them an ongoing decline[1] in carbon dioxide emissions from the electricity sector.

For local economies, however, the closure of a coal-fired power station can create economic challenges, including higher unemployment.

We’ve quantified the effects of 12 closures

In a new paper[2] in the Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, we use detailed Statistical Area Level 4 (SA4[3]) data to quantify the extent to which local unemployment rates have increased following the closures of twelve coal-fired power stations across Victoria, NSW, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia.

There are 87 SA4 regions in Australia, each with an average population of around 290,000 people. We found that on average the regional unemployment rate climbs by around 0.7 percentage points after a station closes.

The effect remains observable for year or two, although it varies from region to region.

Clearly, labour mobility and the creation of new jobs do not fully make up for the impact of such closures.

This means there is scope and need for strategies to smooth the labour market transition as we move towards a lower-carbon energy system.

What we found

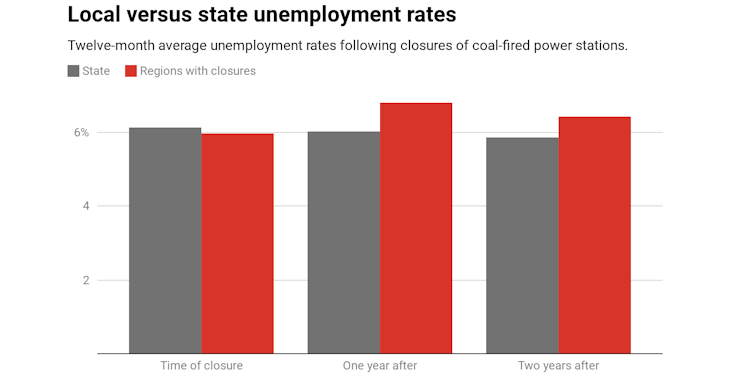

A simple look at the data indicates that local unemployment rates tend to rise after closures, both in absolute terms and relative to what is happening at the state level.

We find that this effect remains when controlling for the impacts of other key factors, such as macroeconomic shocks and the coal export price.

Burke, Best, Jotzo, 2019[4]

Typically the increase in the first year is around 0.7 percentage points – for example, from 6.0% prior to a closure to 6.7% afterwards. It is a sizeable effect. For males the increase is 0.9 percentage points.

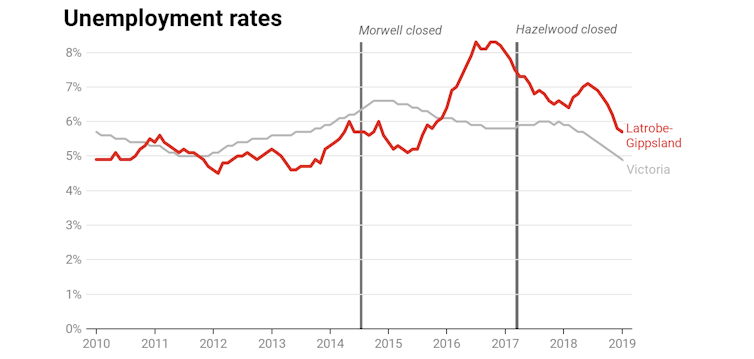

The Latrobe Valley in Victoria faces one of the biggest structural adjustment challenges. It has seen two closures of coal-fired power stations in recent years: Morwell in 2014 and Hazelwood in 2017.

As the graph below indicates, the average unemployment rate in the Latrobe-Gippsland SA4 region climbed well above the Victorian average after the first closure, before turning down.

Burke, Best, Jotzo, 2019[4]

Typically the increase in the first year is around 0.7 percentage points – for example, from 6.0% prior to a closure to 6.7% afterwards. It is a sizeable effect. For males the increase is 0.9 percentage points.

The Latrobe Valley in Victoria faces one of the biggest structural adjustment challenges. It has seen two closures of coal-fired power stations in recent years: Morwell in 2014 and Hazelwood in 2017.

As the graph below indicates, the average unemployment rate in the Latrobe-Gippsland SA4 region climbed well above the Victorian average after the first closure, before turning down.

ABS Labour Force, detailed[5]

A multitude of local transition efforts are underway, coordinated by the Latrobe Valley Authority[6]. These have included a worker transfer scheme[7] that has found places for displaced employees at other power stations.

At the even finer-grained level SA2 level, the unemployment rate in the town of Morwell remaines stuck at around 17%[8], one of the highest rates in Victoria, years after the closure. Before the closure it was around 13%.

The region’s remaining power stations – Yallourn W, Loy Yang A and Loy Yang B – are ageing. Yallourn W is the oldest, at 45 years.

We need to prepare

Structural change is an ever-present feature of a healthy economy. But, especially where rapid structural change happens due to closures of large plants in regional areas, it is important to have measures in place to ease the transition.

The Labor party has promised a national Just Transition Authority[9] to plan for and manage the transition process as coal-fired power stations close. Whether it can help mitigate rises in local unemployment after plant closures remains to be seen.

Many of Australia’s remaining coal-fired power stations are likely to close over the next decade or two as renewable energy becomes more cost competitive and the pressure increases to meet emissions targets. The next cab off the rank is likely to be the Liddell power station in the NSW Hunter Valley, which is due to cease coal-fired operations in 2022[10].

And then there’s the larger question of the transition away from coal mining. Export demand for coal is set to fall over time[11], winding back a large export industry in New South Wales and Queensland.

The Just Transition Authority[12] will have its work cut out.

This research was supported by the Coal Transitions Project and the Australian-German Energy Transition Hub. An open access version of the research paper is available here[13].

ABS Labour Force, detailed[5]

A multitude of local transition efforts are underway, coordinated by the Latrobe Valley Authority[6]. These have included a worker transfer scheme[7] that has found places for displaced employees at other power stations.

At the even finer-grained level SA2 level, the unemployment rate in the town of Morwell remaines stuck at around 17%[8], one of the highest rates in Victoria, years after the closure. Before the closure it was around 13%.

The region’s remaining power stations – Yallourn W, Loy Yang A and Loy Yang B – are ageing. Yallourn W is the oldest, at 45 years.

We need to prepare

Structural change is an ever-present feature of a healthy economy. But, especially where rapid structural change happens due to closures of large plants in regional areas, it is important to have measures in place to ease the transition.

The Labor party has promised a national Just Transition Authority[9] to plan for and manage the transition process as coal-fired power stations close. Whether it can help mitigate rises in local unemployment after plant closures remains to be seen.

Many of Australia’s remaining coal-fired power stations are likely to close over the next decade or two as renewable energy becomes more cost competitive and the pressure increases to meet emissions targets. The next cab off the rank is likely to be the Liddell power station in the NSW Hunter Valley, which is due to cease coal-fired operations in 2022[10].

And then there’s the larger question of the transition away from coal mining. Export demand for coal is set to fall over time[11], winding back a large export industry in New South Wales and Queensland.

The Just Transition Authority[12] will have its work cut out.

This research was supported by the Coal Transitions Project and the Australian-German Energy Transition Hub. An open access version of the research paper is available here[13].

References

- ^ decline (www.environment.gov.au)

- ^ new paper (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ SA4 (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ Burke, Best, Jotzo, 2019 (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ ABS Labour Force, detailed (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ Latrobe Valley Authority (lva.vic.gov.au)

- ^ worker transfer scheme (lva.vic.gov.au)

- ^ 17% (docs.jobs.gov.au)

- ^ Just Transition Authority (theconversation.com)

- ^ in 2022 (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ is set to fall over time (coaltransitions.files.wordpress.com)

- ^ Just Transition Authority (theconversation.com)

- ^ here (ccep.crawford.anu.edu.au)

Authors: Paul Burke, Associate Professor, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University