Australia's sudden ultra-low economic growth ought not to have come as surprise

- Written by Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

Australia’s big little economic lie was laid bare on Wednesday.

National accounts figures show that the Australian economy grew by just 0.2%[1] in the last quarter of 2018. This disappointing result was below market expectations and official forecasts of 0.6%. It put annual growth for the year at just 2.3%.

But the shocking revelation was that Gross Domestic Product per person (a more relevant measure of living standards) actually slipped in the December quarter by 0.2%, on the back of a fall of 0.1% in the September quarter.

These are the first back-to-back quarters of negative GDP per capita growth in 13 years - since 2006.

We’re going backwards, for the first time in 13 years

The reason this is significant is that the Australian convention around what constitutes a recession is two back-to-back quarters of negative GDP growth.

Since more people in the economy mechanically increases overall GDP, you might think that measuring things on a per-person basis gives a better sense of whether we are better off or worse off.

And you would be right. Why then, do we talk so much about overall GDP?

One answer is that in a lot of advanced economies there isn’t very much population growth, so overall GDP is a good enough measure.

Population growth hides it

The more insidious answer in Australia is that, for a long time, our high population growth, fed by a high immigration rate, has masked a much less rosy picture of how we are doing. And neither side of politics has wanted to admit it.

At 1.6% a year, Australia’s population growth is roughly double the OECD average, which is perhaps why we hear politicians say things like “Australia continues to grow faster than all of the G7 nations except the United States,” as Treasurer Josh Frydenberg did this week.

The good news is that standard economic theory tells us that in the long run, immigration has very little impact on GDP per capita in either direction, unless it drives a shift in the population’s mix of skills.

But in the short term, it depresses GDP per capita because fixed capital such as buildings and machines has to be shared between more workers.

Read more: Solving the 'population problem' through policy[2]

The business lobby doesn’t want us to focus on that because population provides more customers as well as more workers, allowing them to grow without growing domestic market share or exports.

Governments don’t want us to focus on it because adjusting for population growth makes GDP growth look small or, as at present, negative. Also, the tax revenue from the population growth is factored into the official budget forecasts – but the extra social spending needed isn’t always factored in.

Pro tip: watch for population growth as a fudge factor generating a return to surplus in next month’s budget.

There’s a better way of getting at the truth

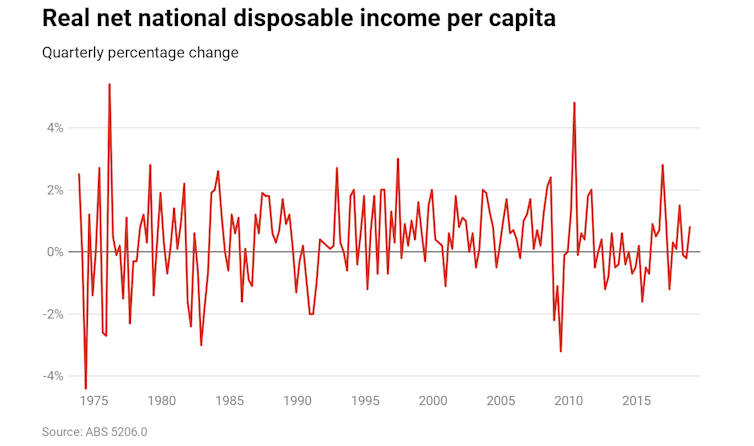

That said, GDP itself – per capita or not – is not a great measure of the standard of living. That’s why in 2001, the Bureau of Statistics began also reporting real net national disposable income[3].

It is a measure with advantages over GDP. As the bureau points out, it takes account of changes in the prices of our exports relative to the prices of our imports - our terms of trade. If the prices of our exports were increasing much faster than the prices of our imports (as happened during the mining booms), our standard of living would climb and real net national disposable income would reflect it, where as gross domestic product would not, although it would reflect increased income from increased export volumes.

To get at living standards per person, which is what we are really interested in, the bureau also publishes real net national disposable income per capita.

The graph shows that so far the growth rate of real net national disposable income per capita hasn’t changed much, and that it has been negative for far fewer quarters than in the Coalition’s first term in office.

It bounces around with changes in the prices of imports and exports, and is generally climbing less than when export prices were really high.

A year of two halves?

The treasurer painted 2018 as a “year of two halves”.

The first half was great - the annualised GDP growth rate (what it would have been had it continued all year) was a very impressive 3.8%.

The second half was just 1%.

I’m not sure the change was that clear cut. As I wrote last September[4], there have been troubling signs for some time, despite the solid headline growth.

Household savings have been plummeting, real wage growth has been stagnant, housing prices have been falling in Sydney and Melbourne. Together they put significant pressure on household spending, which accounts for about 60% of GDP.

Those concerns are now mainstream. Good news on export prices has rescued tax receipts for the time being, and will probably also rescue real net national disposable income per capita.

Read more:

Vital Signs: National accounts show past performance no guarantee of future results[5]

But the fundamentals of the Australian economy are looking somewhat weak. Like the US and other advanced economies, we are living in an era of secular stagnation – a protracted period of much lower growth than we had come to expect.

And until we do something to tackle it, such as a major government investment in physical and social infrastructure, we will continue to face anaemic wage growth, shaky consumer confidence, and mediocre economic growth per person.

The graph shows that so far the growth rate of real net national disposable income per capita hasn’t changed much, and that it has been negative for far fewer quarters than in the Coalition’s first term in office.

It bounces around with changes in the prices of imports and exports, and is generally climbing less than when export prices were really high.

A year of two halves?

The treasurer painted 2018 as a “year of two halves”.

The first half was great - the annualised GDP growth rate (what it would have been had it continued all year) was a very impressive 3.8%.

The second half was just 1%.

I’m not sure the change was that clear cut. As I wrote last September[4], there have been troubling signs for some time, despite the solid headline growth.

Household savings have been plummeting, real wage growth has been stagnant, housing prices have been falling in Sydney and Melbourne. Together they put significant pressure on household spending, which accounts for about 60% of GDP.

Those concerns are now mainstream. Good news on export prices has rescued tax receipts for the time being, and will probably also rescue real net national disposable income per capita.

Read more:

Vital Signs: National accounts show past performance no guarantee of future results[5]

But the fundamentals of the Australian economy are looking somewhat weak. Like the US and other advanced economies, we are living in an era of secular stagnation – a protracted period of much lower growth than we had come to expect.

And until we do something to tackle it, such as a major government investment in physical and social infrastructure, we will continue to face anaemic wage growth, shaky consumer confidence, and mediocre economic growth per person.

References

- ^ by just 0.2% (www.ausstats.abs.gov.au)

- ^ Solving the 'population problem' through policy (theconversation.com)

- ^ real net national disposable income (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ last September (theconversation.com)

- ^ Vital Signs: National accounts show past performance no guarantee of future results (theconversation.com)

Authors: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW