Greens’ election hubris – how the minor party lost its way and now its leader

- Written by Josh Holloway, Lecturer in Government in the College of Business, Government and Law, Flinders University

The Greens’ federal election result has been widely condemned as a “disaster[1]”.

The party has been all but wiped out in the House of Representatives. It has lost three of its four members, including leader Adam Bandt, who has just conceded[2] his once safe seat of Melbourne[3]. This leaves the Brisbane electorate of Ryan as the Greens’ only remaining seat in the lower house.

Yet the tired explanations being rolled out – the party is too extreme, too obstructionist, too distant from a mythical single-issue environmentalist past – misidentify the party’s dilemmas.

And they overlook the fact the Greens’ influence will be greater in the new parliament, at least in the Senate.

Under-delivering

The Greens share the blame for the tone of these election post-mortems.

This is a party of campaign hubris, consistently over-promising and under-delivering.

Bob Brown’s “green government[4]” is yet to emerge. Christine Milne’s aspirations of gains in the bush[5] barely materialised. And the “small-l liberals[6]” chased by Richard Di Natale now prop up independents.

Bandt’s list of new target seats[7] appears to have stretched resources too thin and underscored the challenges of taking a Senate party into the House.

The campaign narrative[8] of “keeping Dutton out and getting Labor to act” may have suited a time when either a Labor or Coalition minority government was a possibility. But it did little to distinguish the Greens as Labor gained momentum.

Many voters may have thought kicking Peter Dutton out was best done by voting for Labor, backed up by supporting the Greens in the Senate to encourage more ambitious Labor action.

National vote holds up

And yet – is the election result all that bad?

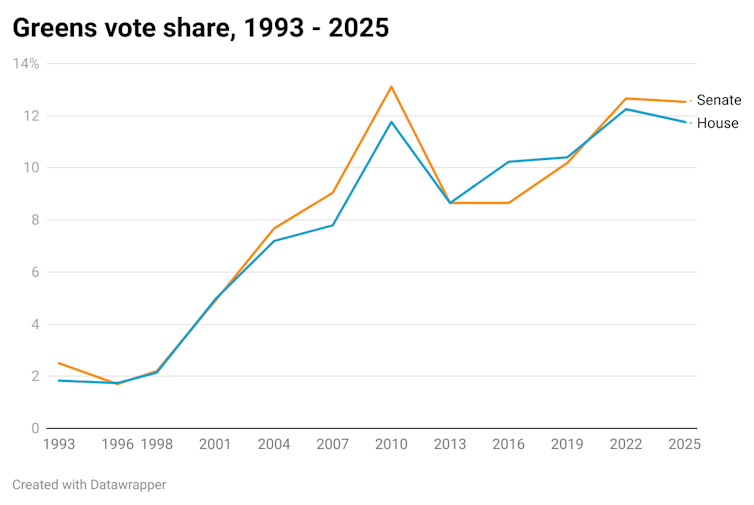

Despite a small negative swing, the Greens’ nationwide primary vote was still above 12%. This election sits alongside 2010 and 2022 as among the party’s largest ever share[9] of votes.

Support ticked up in seats as divergent as Lalor, Fraser, Macarthur, Barton, Newcastle, Page, Spence, and Swan. Even in divisions lost to Labor, such as Griffith[10] and Brisbane[11], voters did not abandon the party in large numbers.

The Greens reaped neither the benefits of opposition nor those of compromise, but instead the costs of both. It’s hard to see crucial segments of voters in lower house seats not being repulsed by this, even as the party finds sufficient support to meet Senate quotas.

Way forward

The future requires serious internal reflection on who the party appeals to, and how.

A new parliamentary strategy is needed to leverage Senate balance of power for progressive outcomes and electoral growth. Greens also need to navigate a relationship with the government that is seemingly hostile to the very existence of the party (has anyone mentioned the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme[20] yet?).

With the loss of Bandt from parliament, the party’s leadership – spilled following an election, regardless of outcome – is now wide open.

Who will lead the Greens now?

Bandt’s replacement will need to balance electoral appeal with an ability to contain internal ructions[21] that have diminished, not disappeared.

Senator Larissa Waters[22] ought to be a frontrunner. She has held leadership positions for 10 years and is popular, both electorally and internally. Crucially, she represents Queensland, a state where the Greens need to regain votes.

Another option is Senator Nick McKim[23], who would return the party’s centre of gravity to Tasmania, and offer previous state party leadership experience.

Another candidate could be Senator Sarah Hanson-Young[25], who has long held leadership aspirations[26].

In a party where members are stridently advocating for greater say in leadership selection, the process could open up and be unpredictable.

All is not lost

The Greens do best when voters turn away from Labor.

As the government advances an unambitious agenda of, at best, “thin labourism[27]”, the number of disappointed and disaffected voters will grow.

Even a modest swing against Labor at the next election puts several House seats back in play, alongside the Greens’ ongoing presence in the Senate.

References

- ^ disaster (www.3aw.com.au)

- ^ just conceded (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ Melbourne (tallyroom.aec.gov.au)

- ^ green government (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ gains in the bush (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ small-l liberals (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ list of new target seats (greens.org.au)

- ^ narrative (greens.org.au)

- ^ largest ever share (greens.org.au)

- ^ Griffith (tallyroom.aec.gov.au)

- ^ Brisbane (tallyroom.aec.gov.au)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ balance of power (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ voters’ preferences (www.afr.com)

- ^ held (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ social democratic (www.theaustralian.com.au)

- ^ housing agenda (www.sbs.com.au)

- ^ ultimately capitulating (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ Jono Searle/AAP (photos.aap.com.au)

- ^ Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme (www.crikey.com.au)

- ^ internal ructions (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ Larissa Waters (www.aph.gov.au)

- ^ Nick McKim (www.aph.gov.au)

- ^ Mick Tsikas/AAP (photos.aap.com.au)

- ^ Sarah Hanson-Young (www.aph.gov.au)

- ^ leadership aspirations (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ thin labourism (politicalquarterly.org.uk)