The AFL has moved the grand final from Melbourne for the first time – but it has a far more pressing issue

- Written by Gregory Phillips, Adjunct Professor, Griffith University

In a year shaped by climate disasters and a pandemic, Australia’s most powerful sporting organisation – the Australian Football League (AFL) – continues to be confronted by another foundational issue: systemic racism.

At issue is not only the question of how the Australian sports industry engages with the Black Lives Matter movement, but also the continued failure of key Australian organisations to adequately reflect on, and reform, their own colonial values and power structures.

A continued failure to address racism

While the AFL would likely prefer attention was focused on the historic move of the men’s grand final outside Victoria[1], the continued distress caused by racism within the game is a more pressing issue.

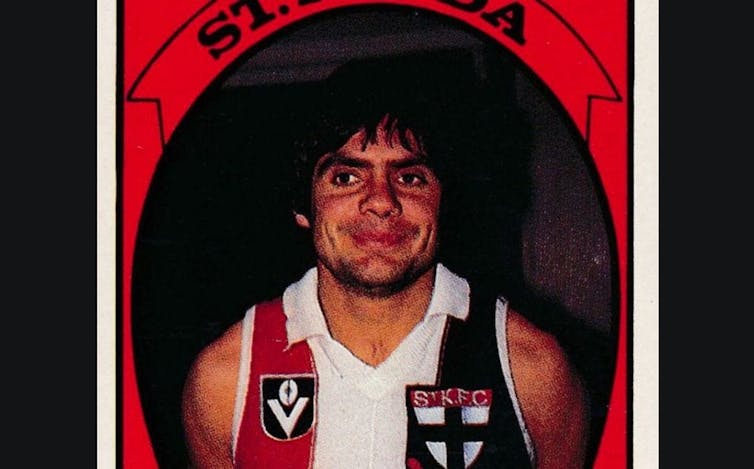

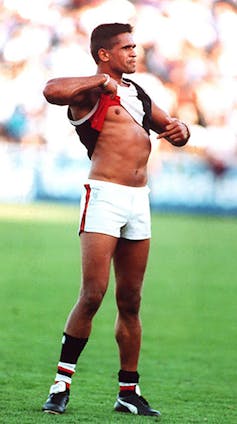

Most recently, the AFL’s 2020 Sir Doug Nicholls Round[2], set up to celebrate Indigenous Australian contributions to football, was overshadowed by the story of how racism in football has traumatised Yorta Yorta man Robert Muir[3].

Muir was persecuted at a junior level (being unjustly suspended for two-and-a-half years for the falsified charge of kicking), humiliated by his St Kilda VFL teammates and routinely abused by many opposition players and supporters. He was then largely neglected by St Kilda, which used an image of him in the club’s heralded 2019 Reconciliation Action Plan[4], but never even spoke with him.

The mistreatment of Muir is not merely testament to how racist Australia used to be. It is also indicative of Australia’s current systemic racism. Just this year, Eddie Betts[5], Shelley Ware[6], Elijah Taylor[7] and Harley Bennell[8] (among others) have been repeatedly subjected to vile racist abuse via various social media platforms. These are not isolated incidents, but represent a pattern of abuse.

Héritier Lumumba was largely ignored when he spoke out against racism.

Joe Castro/AAP

Héritier Lumumba was largely ignored when he spoke out against racism.

Joe Castro/AAP

When Muir tried to speak out about the racist vilification he received, he was not believed. Over 40 years later, Héritier Lumumba was also largely dismissed when he first spoke out about the racism he experienced at the Collingwood Football Club. This included[9] being given the nickname “Chimp” by some teammates. It has taken until now for Collingwood to instigate a formal investigation[10] into Lumumba’s treatment and broader institutional issues.

Former Gold Coast Suns player Joel Wilkinson has also spoken out[11] against the systemic racism he experienced.

Read more: Fair Game? The audacity of Héritier Lumumba[12]

The struggle to be believed

The questioning of racism by key figures in the AFL industry remains a significant issue. Many people responded with outrage and sympathy to Muir’s tale. The AFL[13], St Kilda[14], Geelong[15], Collingwood[16] and the Ballarat Football League[17] (among others) apologised for the acts of racism that Muir endured.

However, AFL Hall of Fame member Mick Malthouse suggested Muir tried to “live up to” his racist “Mad Dog” nickname[18], and suggested the racist slur “served him well”.

The AFL and St Kilda Football Club have apologised to Robert Muir for the horrific racism he endured.

afl.com.au

The AFL and St Kilda Football Club have apologised to Robert Muir for the horrific racism he endured.

afl.com.au

Malthouse’s comments bring to mind the 2020 podcast by veteran AFL media figures Sam Newman, Mike Sheahan and Don Scott, which trivialised Nicky Winmar’s iconic 1993 gesture against racism. They suggested Winmar was merely saying he had “guts”[19].

In a telling instance of the erasure of the history of racism in the AFL, Sheahan had presumably forgotten that just one week after Winmar’s defiant gesture he had written (in an article about Essendon coach John Worsfold regretting he had “used racist remarks”):

The debate on racism in football came to a head this week after St Kilda’s Nicky Winmar’s on-field protest around racism last Saturday. He lifted his guernsey, pointed at his chest, and told the crowd: ‘I’m black – and I’m proud to be black.’

The AFL often uses this famous image of Nicky Winmar to market its fight against racism.

National Museum of Australia

The AFL often uses this famous image of Nicky Winmar to market its fight against racism.

National Museum of Australia

The AFL frequently uses the image of Nicky Winmar to market itself as an organisation and industry that helps lead the fight against racism in Australia. Yet even its celebration of Sir Doug Nicholls indicates that broader issues, both structural and symbolic, remain unaddressed[20].

After being racistly excluded from playing VFL by Carlton[21], Sir Doug starred as a footballer for Northcote in the VFA, then Fitzroy in the VFL. He was good enough to be selected in the Victorian sides of both leagues.

Later Sir Doug coached Northcote in the VFA and the first Aboriginal All Stars football team. He did this while he was the inaugural chairman of the National Aboriginal Sports Foundation, which conducted National Aboriginal Football Carnivals in all capital cities.

Yet somehow he is still not in the AFL Hall of Fame.

Saying ‘sorry’ – but it never leads to change

Newman, Sheahan and Scott ended up apologising to Nicky Winmar[22], as the AFL industry has done with Muir, and did earlier with Sydney Swans’ dual Brownlow medallist Adam Goodes, who was driven out of the game by racist booing and the conspicuous failure of the AFL to support him. This pattern of denial, then apology, then repeating abuse, then denial again, then another apology, is not unique to corporatised sporting codes. It is emblematic of a broader pattern of Australian corporate, government and non-government organisations defensively making Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and their outcomes “the problem” to be “helped”.

So how should the AFL better redress systemic racism and ensure that Black Lives do Matter? Certainly not by blaming the individual Black workers responsible for institutional white problems.

Read more: The AFL sells an inclusive image of itself. But when it comes to race and gender, it still has a way to go[23]

After the soul-searching with Goodes, the AFL promised[24] it had learned of the need to fully support those people in the AFL industry who are subjected to vile hatred and vilification.

Yet this past week we have seen the leaking of attacks[25] against the league’s only Indigenous executive, who along with other Aboriginal people in the football industry - especially Aboriginal women - shoulder the burden of trying to redress the systemic racism of the football industry. Moreover, there are suggestions the league is also reducing the financial investment[26] and support provided in the diversity area (along with curtailing the freedom of those involved).

And the AFL executive remains largely white and male. It is telling that, as the league lurches from crisis to crisis regarding racism, it is the Indigenous leader of “inclusion and social policy” whose position is under threat. This is also made worse by lateral violence from otherwise dis-empowered voices. That the messenger becomes attacked is indicative of a culturally unsafe organisation.

At the same time, Eddie McGuire continues to not only be president of Collingwood, but to hold great power within the AFL media, despite his history of racist comments[27] and other “gaffes”.

What kinds of culturally safe work environments can Aboriginal nurses, doctors, policymakers, teachers or indeed AFL players expect from their workplaces? And where are the unions, businesses and governments that should be demanding accreditation and accountability systems for anti-racist workplaces? Where are the investments in something other than colourfully designed guernseys and displays of cultural pride – critical though these are?

Read more: How COVID caused chaos for cricket – and may force a rethink of all sport broadcasting deals[28]

An undiagnosed crisis of values is afoot. When we think of those young, vulnerable men and women in the arena and in the locker-rooms, and the fans and sponsors and controllers of the industry – all desperate for belonging, ceremony and triumph, we think perhaps they could learn something from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples as the custodians of 60,000 years of science and deep belonging.

There are organisations and industries undertaking strategic efforts at decolonisation. We implore the AFL and other industries to join that effort, because it is good for business and good for our grandchildren. Why not use the crises as signposts to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander brilliance and success, and their value to all?

Put simply, Black Peoples do not represent an issue of diversity, but one of sovereignty.

References

- ^ the historic move of the men’s grand final outside Victoria (www.afl.com.au)

- ^ Sir Doug Nicholls Round (www.afl.com.au)

- ^ how racism in football has traumatised Yorta Yorta man Robert Muir (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ 2019 Reconciliation Action Plan (s.afl.com.au)

- ^ Eddie Betts (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ Shelley Ware (www.theage.com.au)

- ^ Elijah Taylor (www.thecourier.com.au)

- ^ Harley Bennell (www.perthnow.com.au)

- ^ included (theconversation.com)

- ^ formal investigation (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ spoken out (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ Fair Game? The audacity of Héritier Lumumba (theconversation.com)

- ^ AFL (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ St Kilda (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ Geelong (twitter.com)

- ^ Collingwood (www.theage.com.au)

- ^ Ballarat Football League (www.thecourier.com.au)

- ^ live up to” his racist “Mad Dog” nickname (www.news.com.au)

- ^ was merely saying he had “guts” (www.theage.com.au)

- ^ remain unaddressed (theconversation.com)

- ^ racistly excluded from playing VFL by Carlton (www.afl.com.au)

- ^ ended up apologising to Nicky Winmar (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ The AFL sells an inclusive image of itself. But when it comes to race and gender, it still has a way to go (theconversation.com)

- ^ the AFL promised (theconversation.com)

- ^ leaking of attacks (www.theage.com.au)

- ^ also reducing the financial investment (www.theage.com.au)

- ^ racist comments (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ How COVID caused chaos for cricket – and may force a rethink of all sport broadcasting deals (theconversation.com)