new research examines why people choose to serve and who makes the ideal soldier

- Written by Robert Hoffmann, Professor of Economics, Tasmanian Behavioural Lab, University of Tasmania

The recent investigations into alleged war crimes committed by Australian[1] and UK special forces[2] in Afghanistan have raised urgent questions about the conduct of people serving in the military.

As militaries rethink their structures and the complex role they play in society, they also need to examime what types of people they should be recruiting. Who are the modern soldiers, and why do they choose to serve?

Some of these answers can be found in existing research that defence forces have conducted over the last half century. With the end of conscription in many Western nations, volunteer militaries began to commission studies looking at why people enlist. The findings were meant to make recruitment campaigns more effective[3].

We recently conducted a research project funded by the Australian Defence Force that examined these studies through a new lens of behavioural science.

The aim of this study went beyond just increasing recruitment numbers, though. Understanding people’s motivations for enlisting can also reveal a lot about the suitability of recruits for the military[4], given the new demands they face in these roles.

We found that in contrast to the usual portrayal of military recruits as Hollywood- inspired, hyper-masculine mercenary types, many people enlist because of the duty of care for others and the value they place in military service.

Read more: Australian Defence Force must ensure the findings against Ben Roberts-Smith are not the end of the story[5]

Recruiting for a new model military

The role of militaries has changed in recent years. Today’s threats are frequently not active conflicts between nations, but rather ethnic strife within nations, terrorism and cyber warfare. Peacekeeping and humanitarian missions have also become more common than conventional warfare, with military forces frequently involved in disaster relief and recovery efforts.

The lines around the purpose of a military are now increasingly blurred. As a result, public sentiment and the battle for hearts and minds has become even more important, especially as technology and social media allow domestic audiences to be better informed about what happens in the field.

The now-deceased sociologist Charles Moskos[6] called this the “postmodern military”. It is much leaner and more professional than the armed forces of the past, tasked with new kinds of missions, oftentimes without widespread public support[7].

New model armies need new model recruits. So, what drives a person to want to voluntarily enlist?

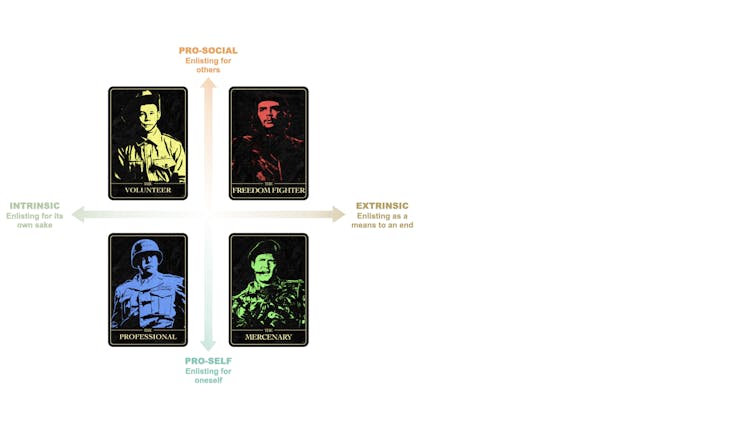

We found the voluminous evidence can be neatly captured by two separate dimensions:

Serving for thrills and adventure

Intrinsically motivated people[8] do things for their own sake. For example, they might like travelling for the journey itself, rather than to reach a destination.

Independent of outcomes, some recruits are motivated to serve in the military by the idea of service itself. This could include having an inherent interest in the military, learning how to use high-tech machinery and a sense of adventure.

Melbourne University researcher Sara Meger[9] found many foreign fighters have been attracted to international flashpoints like Ukraine because of thrill-seeking.

Some people also sign up for the military out of a personal psychological need for stimulation. One military study[10] shows volunteer soldiers have a greater tolerance for risk-taking than non-volunteers.

Read more: 'Fit for service': Why the ADF needs to move with society to retain the public trust[11]

Service as a means to an end

On the other end of this spectrum are those who are driven purely by extrinsic motives. This means doing something in the pursuit of a separate goal, such as financial compensation, or recognition earned through medals.

In Meger’s interviews with foreign fighters on both sides of the Ukraine conflict, she found they were often extrinsically driven by ideology. Serving was a way to support a desired political outcome, such as Ukraine’s self-determination[12].

Other British and American fighters were driven[13] by the goal of protecting Ukraine – and the Western world generally – from what they saw as Russian President Vladimir Putin’s threat to freedom.

These people consider themselves freedom fighters, like Che Guevara[14], and will accept extraordinary risks and hardship. They often have military backgrounds, too.

Serving for others vs for oneself

Some soldiers are driven for a pro-social reason, as in they are serving for others. These people can be motivated by altruistic reasons, such as defending one’s country and loved ones at great risk and cost to themselves. Some serve as a way to provide better support to their families.

On the other end of the scale are those with self-interested motivations to serve. These can include personal advancement, income, training and career opportunities. Escapism is another common motive found – many serve to cope with relationship breakdown or financial or family stress[15].

Extrinsic motivation and self-interest are not the same[16]. Freedom fighters, for example, fight for an extrinsic outcome (winning a war), but might do so out of consideration for others (those who win their freedom).

And intrinsic motivations are not always pro-social. Adventure seekers care about fighting rather than winning, for purely selfish reasons.

Put together, these motivations reveal four service archetypes: the volunteer, the freedom fighter, the professional and the mercenary. But the research suggests most people will have a variety of motivations and lie somewhere between the extremes.

So, who is the ideal soldier?

How do these insights help the military? Defence forces have much to gain from recruiting volunteers with the right mix of intrinsic and pro-social motivations.

The psychological evidence suggests that people with intrinsic motivations lead to a better quality of service[17]. They are motivated by discipline, technical proficiency and professionalism, meaning they are more likely to perform in line with what society expects of them.

But the evidence also suggests these motivations can be “crowded out” when excessive rewards are offered. This means providing an extrinsic incentive for something reduces the intrinsic motivation for it[18].

For instance, British social policy pioneer Richard Titmuss’s[19] well-regarded analysis suggests that paying people for blood donations takes away their opportunity to demonstrate public spiritedness. This was later confirmed in empircal studies[20].

On the other spectrum, pro-socially oriented people are well-suited for humanitarian missions or in interactions with civilians caught up in conflict.

Multinational companies and organisations are already using this type of behavioural scientific research to find the best candidates for their workforce. As militaries rethink their purpose to keep up with the times, they can learn much from mulitnationals on this front.

In the postmodern military, recruiting isn’t just about filling the ranks anymore, it’s about finding the right fit for an increasingly challenging profession.

References

- ^ Australian (theconversation.com)

- ^ UK special forces (www.bbc.com)

- ^ recruitment campaigns more effective (www.rand.org)

- ^ suitability of recruits for the military (www.jstor.org)

- ^ Australian Defence Force must ensure the findings against Ben Roberts-Smith are not the end of the story (theconversation.com)

- ^ sociologist Charles Moskos (www.foreignaffairs.com)

- ^ oftentimes without widespread public support (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ Intrinsically motivated people (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ Melbourne University researcher Sara Meger (amp.abc.net.au)

- ^ One military study (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ 'Fit for service': Why the ADF needs to move with society to retain the public trust (theconversation.com)

- ^ such as Ukraine’s self-determination (hir.harvard.edu)

- ^ driven (hir.harvard.edu)

- ^ Che Guevara (www.thecollector.com)

- ^ cope with relationship breakdown or financial or family stress (academic.oup.com)

- ^ not the same (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ lead to a better quality of service (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ reduces the intrinsic motivation for it (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ Richard Titmuss’s (www.sapiens.org)

- ^ This was later confirmed in empircal studies (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)