Why robodebt's use of 'income averaging' lacked basic common sense

- Written by Peter Whiteford, Professor, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

The practice of “income averaging” to calculate debts in the robodebt scheme was completely flawed. This is what I confirmed in my new report[1] conducted for the robodebt royal commission published last Friday, the final day of the commission’s public hearings.

This process effectively assumed many people receiving social security benefits had stable earnings throughout a whole year.

But this is unlikely to be accurate for the many people who don’t work standard full-time hours[2], and particularly for students, since the tax year and the academic year don’t coincide.

My report finds averaging of incomes is completely inconsistent with social security policies that have been developed by governments since the 1980s.

Since 1980, social security legislation has been amended more than 20 times to encourage recipients to take up part-time and casual work. These include the Working Credit[3] for people receiving unemployment and other payments, and a similar but more generous Income Bank[4] for students.

These measures are specifically designed to encourage people to take up more work[5], including part-time and irregular casual work, and keep more of their social security payments.

Robodebt’s lack of consistency with long-standing policies should have been obvious from the start.

What is income averaging?

In the robodebt scheme, income averaging involved data-matching historic records of social security benefit payments with past income tax returns, identifying discrepancies between these records.

It reduced human investigation of the discrepancies. The automatic calculation of “overpayments” for many people was based on a simple calculation that averaged income over the financial year.

The “debts” were based on the difference between this averaged income and the income that people actually reported while they were receiving payments.

I wrote an article[6] for The Conversation on this in 2017. At the time, I thought, Centrelink couldn’t possibly have done that.

Well, as the royal commission has found, that’s precisely what it was doing[7].

Read more: Note to Centrelink: Australian workers' lives have changed[8]

A victim of robodebt, Deanna Amato, brought a test case[9] to the Federal Court in 2019, which caused the government to admit robodebt was unlawful.

Amato also gave evidence at the royal commission in late February this year[10]. She described how it was obvious her debt was in error:

It was averaged over the […] whole financial year. Study usually starts at the beginning of a calendar year. So I had been working full-time for the first six months of that year and then I had stopped working full-time to study. So it was really obvious that they had averaged out over the whole year rather than the six months I was actually only claiming Austudy for.

What I found

It’s well known Australia has a high proportion of casual workers.

Because they’re employed on an “as needed” basis, their hours can vary substantially. Therefore, their income can too.

ABS data showed that in 2014 nearly 40%[11] of casual workers didn’t work the same hours each week. Also, around 53% had pay that varied from one pay period to another. These figures have been broadly stable since 2008.

Read more: Robodebt was a fiasco with a cost we have yet to fully appreciate[12]

My report analyses new data provided by the Department of Social Services to the royal commission. It looks in detail at the circumstances of people who received social security payments between 2010-11 and 2018-19. These payments included Austudy, Newstart, Parenting Payment Partnered, Parenting Payment Single and Youth Allowance.

These payments accounted for around 91%[13] of the people subject to the reviews that identified discrepancies and potential “overpayments” between 2016 and 2019 under the different phases of robodebt.

For Newstart and Youth Allowance recipients – who accounted for 75% of those affected by robodebt[14] – between 20% and 40% had earnings while receiving these benefits.

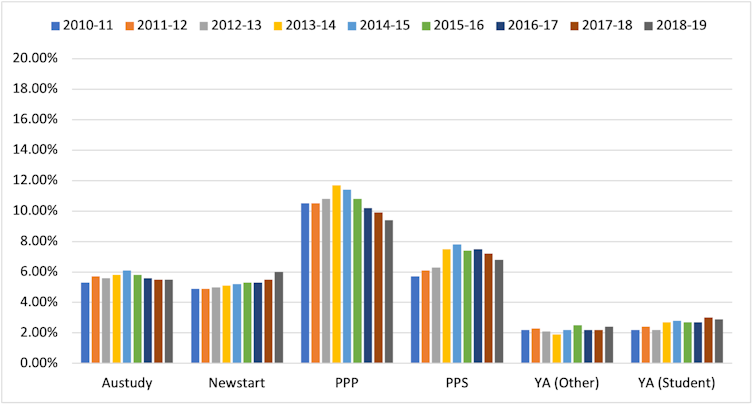

The share of people with income who had stable incomes over the course of the financial year was extremely low. In the Department of Social Services data, it ranged from less than 3% of people receiving youth payments, to around 5% of those receiving Newstart or Austudy, and 5%-10% of those receiving Parenting Payments.

Share of people on social security payments with stable income over the course of each financial year, 2010-11 to 2018-19

References

- ^ my new report (robodebt.royalcommission.gov.au)

- ^ full-time hours (theconversation.com)

- ^ Working Credit (www.servicesaustralia.gov.au)

- ^ Income Bank (www.servicesaustralia.gov.au)

- ^ encourage people to take up more work (formerministers.dss.gov.au)

- ^ an article (theconversation.com)

- ^ precisely what it was doing (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ Note to Centrelink: Australian workers' lives have changed (theconversation.com)

- ^ test case (www.legalaid.vic.gov.au)

- ^ royal commission in late February this year (robodebt.royalcommission.gov.au)

- ^ nearly 40% (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ Robodebt was a fiasco with a cost we have yet to fully appreciate (theconversation.com)

- ^ for around 91% (www.aph.gov.au)

- ^ 75% of those affected by robodebt (www.aph.gov.au)

- ^ a short-term and sometimes recurring experience (theconversation.com)

- ^ The Robodebt scheme failed tests of lawfulness, impartiality, integrity and trust (theconversation.com)

Read more https://theconversation.com/why-robodebts-use-of-income-averaging-lacked-basic-common-sense-201296